We're watching ALL 17 of Montgomery Clift's films for his Centennial. Here's returning contributor David Upton with episode 4.

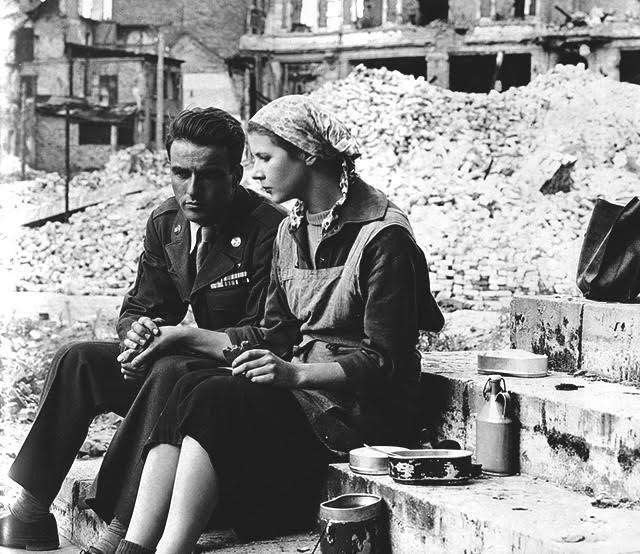

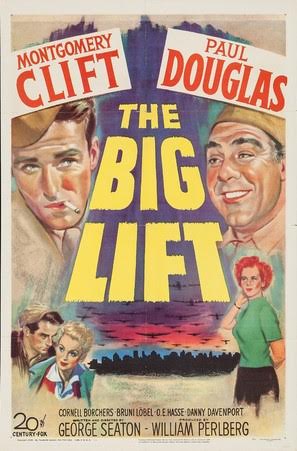

Just two years after his debut in The Search, Montgomery Clift returned to post-war Europe. The Big Lift, released in 1950, was just two years removed from the true story it centres on, the Berlin airlift of 1948. One of the first major crises of the Cold War, the airlift was needed thanks to the Soviet blockade of the part of the city under the control of Western allies. Berlin is a city in ruin, populated by a people torn apart and living amongst rubble. Into this, director George Seaton’s film casts a watchful Monty and the exuberant Paul Douglas as a pair of Air Force sergeants, Danny MacCullough and Hank Kowalski.

Future AMPAS president Seaton, best known for 1947’s whimsical Christmas fantasy Miracle on 34th Street, goes hard on the verité factor, casting all supporting military characters with real Air Force personnel...

The camera keeps low and close in the cockpit, and starkly captures the crumbling vistas of Berlin as the men make their way around the streets. That veracity doesn’t extend to the narrative, which lands somewhere between a goofy romantic comedy and a moralistic tragedy. It makes for an odd experience, with comic contrivance somewhat undermining the earnest depiction of the physical and emotional impacts of conflict and dictatorship - as critic Bosley Crowther put it at the time, the film conveys a “hodgepodge of impressions”.

Coming early in Clift’s career, The Big Lift is overshadowed by the two beloved films surrounding it; and indeed, in production terms, it's of minor concern. Clift flew out to Berlin after dropping out of Sunset Boulevard (reportedly thanks to similarities with his affair with the much older Libby Holman), and his scenes were prioritised to allow him to return to America to film A Place in the Sun. As a Clift vehicle, The Big Lift isn’t exactly memorable; for much of the film, he actively takes a backseat, and large portions of it are handed instead to Douglas, a boorish mouthpiece for American policy and flagbearer for xenophobia who ‘educates’ his cynical German fling Gerda (Bruni Löbel). Clift’s Red River co-star John Wayne had warned Douglas against the newcomer’s narcissism, and on perceiving Clift hogging his space in one of their first scenes, Douglas stamped on his foot and said, “Do that again and I'll break your fucking foot”. While this animosity isn’t particularly apparent on-screen, the narrative separates them as quickly as it can manage, effectively splitting the film into separate political and emotional threads.

The film’s early sequences, as the troops make their way across the Atlantic and are confined to the Berlin air-base, are the film’s most restrained, and Clift - despite the piercing eyes inevitably drawing the viewer’s attention to him among a crowd - follows suit, allowing the real personnel to have characterful moments and embed himself as ‘one of the guys’, respectful of the men as he shares the screen with them. The dialogue at this point feels spontaneous and earthy, and Clift works particularly well as part of the smaller group in the cockpit, gently reactive to the pilots’ dialogue and conveying the idea of routine and rapport built through a shared history. There’s more of a performative, reactive feel to his more public moments, as if Danny is leaning into the macho posturing and jocular rivalries of the military environment. He chews gum constantly, stands awkwardly in the more formal moments, which works to simultaneously underline his position as a backgrounded engineer and also plays to Clift’s more emotional, unfettered instincts.

Like Douglas, Seaton experienced issues with Clift on-set, ordering his acting coach Mira Rustova off the set, until the actor threatened to quit, and Seaton allowed her to return. In retrospect, it may well be that Rustova’s influence gave the film it’s more powerful and resonant moments thanks to Clift’s more measured playing in the face of tonal incoherence.

When Danny meets and pursues a Berlin resident, Frederica (Cornell Borchers), the film lets the two sergeants loose in Berlin, with the combined aim of giving the film a fluffy comic injection while exploring the lives of the population in post-war occupied Germany. Clift brings a boyish energy to Danny’s hunger to escape into the city, and manages some absurd comic moments with a light touch, such as joining a group of singers on-stage to avoid Russian interrogation, but the film’s divided loyalties make Danny a rather inconsistent character. Clift overemphasises his naïve shyness towards Frederica and is less adept at capturing the lust Danny is clearly meant to feel. It’s telling that the film marks their implied sexual union by accompanying their clandestine night-time kiss with a plane taking off in the background, a strange piece of daft innuendo.

Ultimately, Seaton can’t balance the variation in tone, bouncing between comedy and drama and losing his grip on the reality of the film’s initial sequences. What’s more unfortunate, perhaps, is the loss of the power of that reality; the script seems to get distracted by the narrative, at the expense of the gritty truth of what these soldiers experienced - something Clift would have undoubtedly excelled at conveying. It replaces this with a sober climax that attempts to underline the twisted nature of growing up under a fascist regime and the lingering damage on their psyche. Clift brings a keen heartbreak to the realisation of the truth he’d previously been blind to, portentous music accompanying his revelation of the poverty and devastation around him, but again, the film undercuts this impact with some goofy comedy surrounding Germany’s poor phone lines. As Crowther put it, Seaton’s film “lacks cohesion, clarity or magnitude” thanks to its conflicted focus, and leaves its audience wanting in every possible respect.