Some movies are more fascinating than they are engaging, working better as a discussion topic than as cinema. Such pictures tend to find their home in writings about film history or critical academia, living on as curious artifacts that thrive on the page while failing on screen. Montgomery Clift's seventh feature, the only time he ever worked with celebrated Italian auteur Vittorio De Sica, is one of such films. Perhaps more accurately, it's two of them…

By the mid-50s, Italian Neorealism was an international sensation. Since the immediate aftermath of World War II, Italy had been living through a cinematic Renaissance in which up and coming filmmakers pointed the cameras at the bleakness of their country, capturing reality denuded of romantic artifice. Employing plenty of non-professional actors, shooting on location, letting the action take its time instead of cutting through it with editing magic, this new approach to cinema felt revolutionary.

Even though we can find projects with similar qualities earlier in film history, it was the Italians who managed to make the style stick, who popularized it. It's difficult to overstate the importance of Italian Neorealism in the development of the art form, seeing as its influence is still felt today. Curiously enough, unlike what happens nowadays, the American market was ready to embrace the work of the European vanguard. As early as 1946, these films were finding success in the US, both critical and popular.

In 1947, the Vittorio De Sica-directed Shoe-Shine became the first picture to ever win the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. The director would take Italy to a second victory in 1949 with Bicycle Thieves at the same time that his compatriot, Roberto Rossellini, made headlines across the globe due to his affair with Ingrid Bergman. The collaborations between the Italian director and Swedish star, starting with 1950's Stromboli, caused quite the sensation too. More importantly, for Hollywood producers, their pictures proved to be box office successes.

This detailed context is important to understand why, in 1952, David O. Selznick decided to produce a Vittorio De Sica picture starring Jennifer Jones and Montgomery Clift. If pairing a Hollywood star and an Italian auteur had worked once, why couldn't it work twice? It's also easy to see why Montgomery Clift, a young star with lofty artistic ambitions, would be drawn to the project, especially when De Sica was known to give his actors quite a lot of freedom in constructing their performances.

The historical context helps to understand why Terminal Station was made. It also helps us to see why it's, at the end of the day, a marvelous failure.

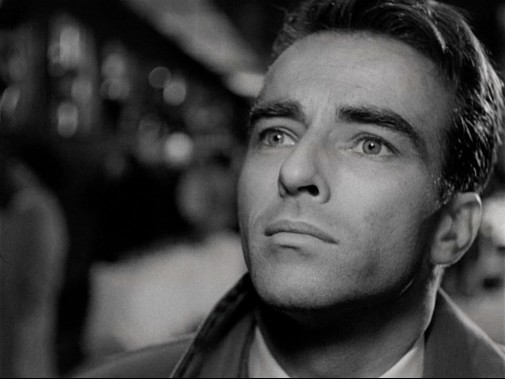

The film's story concerns Mary Forbes, a wealthy Philadelphian housewife who's vacationing in Italy. During her stay, away from her husband and little daughter who are away in Paris, she's become entangled with a dashing Italian man called Giovanni. Scripted to unfold in real-time, Terminal Station portrays Mary's indecision as she wavers between leaving for Paris and consummating her adulterous affair. No matter how stable her marriage may be, one can't blame Mary for feeling tempted by Montgomery Clift at the peak of his beauty, can we?

Much of Terminal Station's first third details Mary's internal struggle expressed in dolorous manner by Jennifer Jones. We watch her come near Giovanni's door, stop herself and then flee to Rome's main train station, a monument of fascistic architecture that's full of people representing every stratum of Italian society, from the destitute to the powerful. There, she tries to get on a train to Paris but is intercepted by Giovanni at the last minute. While she waits for the next train, we watch as the two lovers wander the station, the man desperately trying to convince his beloved to stay.

De Sica and his longtime collaborator Cesare Zavatani conceived the film in a rather odd shape. While the weepy melodrama structures the narrative, the camera's constantly losing interest in the protagonists, preferring to gaze at the lives happening on the margins of their personal affair. It almost feels like a deconstructed piece of Hollywood pablum, a sentimental story dressed in Dior being forcefully thrown into the real world by its maverick director. Instead of feeling organic, the love story comes off like an intrusive presence in the cosmos of real Roman life.

At the same time, the surrounding crowds are never fully fleshed out, the demands of the plot constantly circumventing the background figures from expressing their humanity. It's fascinating, beautifully shot, but not entirely successful. No wonder that, upon seeing the labor of his work, Montgomery Clift is said to have been disappointed, calling the romance a "complete mess". O. Selznick certainly agreed and, in his usual fashion, the husband of Jennifer Jones decided to reconstruct the film to his liking.

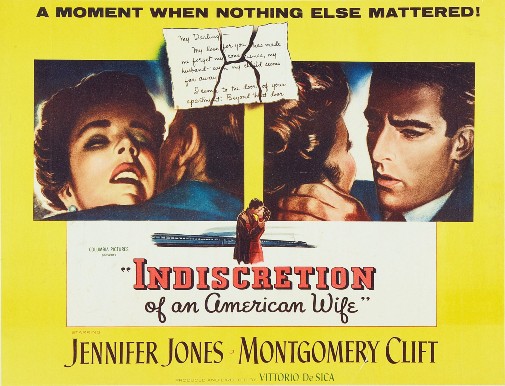

The picture I've been describing until now is Terminal Station, originally titled Stazione Termini, which premiered in Italy in 1953. It's an 89-minute Neorealist melodrama, as thought-provoking as it is discombobulated. That wasn't the picture American audiences saw. Selznick recut the picture, doing away with nearly all of the first third and excising those detours from the main plot. At 64 minutes, this cut, now titled Indiscretion of An American Wife and released in 1954, was too short to be considered a feature, so Selznick shoe-horned a musical "overture" at the start that bears no connection whatsoever to the story of the film.

It's a hack job that strips away almost everything that is interesting about De Sica's vision, leaving behind an anemic melodrama. The actors' work survives the cuts, though Jones loses some of her best and most evocative moments of quiet contemplation. As for Clift, who is the raison d'être for this write-up, after all, most of his performance remains in the abridged flick. However, without the context of De Sica's neorealist reveries, he feels unsettlingly unmoored.

Terminal Station is like a grand choreography wherein Hollywood artifice dances with the stripped-down severity of Italian neorealism. In the middle of that movement, another dance takes place between two very different styles of acting. Jennifer Jones delivers an arch performance as Mary, delineating her patrician fortune with careful gestures and elegant diction. Clift, on the other hand, is a freight train of raw emotion colliding with the ice palace of his costar. Where she's controlled and poised, he's messy and intense, needy, anguished, and fiery too. Watching them together is akin to getting a lesson on the evolution of screen acting in the 20th century.

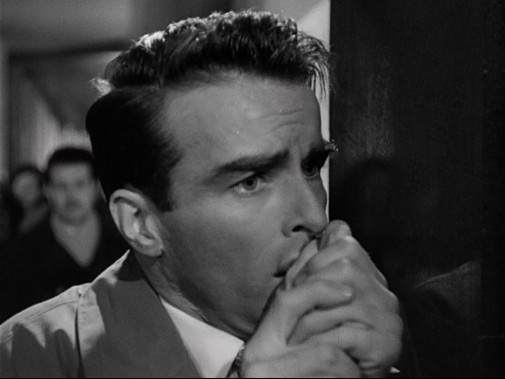

It's hard to classify Montgomery Clift's work as good or bad. Like the film it's in, the performance is more interesting than any quick qualitative judgment might imply. Jones' Mary is always resisting her desires, but Clift's Giovanni fully surrenders to them, lighting a flame of eroticism that warms up the movie and threatens to give it a pulse when energy starts to wane. His lustful obsession with the married woman is often the most real thing on-screen, transcending realism itself to get at some sort of primordial human emotion that can only exist when couched in fiction.

In a movie that often feels like it's on narrative autopilot, Clift's work adds a note of uncertainty to the proceedings. There's keen volatility to his screen presence, a hint of casual self-destruction that puts him closer to Isabelle Adjani's Adele H than to Trevor Howard's Alec Harvey on the scale of rejected lovers of the big screen. At times, one gets the sense that he might easily succumb to a violent impulse and, when sharing the screen with Mary's kid nephew, it's difficult to discern which character is more willfully immature.

All things considered, Giovanni Doria isn't one of Montgomery Clift's greater creations. Trapped inside two unbalanced versions of the same movie, the actor was sadly unable to overcome the challenges put forward by Terminal Station. Even so, I'd recommend this film to any fans for it showcases his methodology, his strengths, and weaknesses in a wonderfully stark fashion. Sometimes, one can better understand an artist's characteristics, their value, and the specificities of their craft, when seeing them without the glaring shine of undisputable triumph encumbering our perception.

Still, make sure to watch the original Italian cut and not Selznick's abomination.