Please welcome new contributor Patrick Gratton...

To succeed in Hollywood, one must finesse the art of self-branding. Moving up the echelon of struggling up-and-comers trying to break out is, often enough, an impossible task. Self-branding helps gets you through doors and to build a following. It also builds the foundation for narratives, whether it be industry, populist or award based (these narratives don’t happen in a vacuum). But brands can be a double-edged sword, pigeonholing and often crippling the potential to explore and grow as an artist. Winning Oscars early on in one’s career is problematic too. It can either derail a narrative, or implement a forced one. Today, commemorating Matt Damon's 50th birthday, let's look at how major misconceptions of his work have plagued him through a 30 year run on screen.

As narratives go, sometimes it’s a burden to win an Oscar at the outset of someone’s career. Granted, Damon’s Oscar for Gus Van Sant’s 1997 film Good Will Hunting, was for the screenplay he co-wrote with childhood best friend and soon-to-be Hollywood heartthrob Ben Affleck, and not for his performance, but the point still stands...

Damon was Hollywood’s newest commodity, an up and coming self-made man who, despite a few supporting credits to his credit, knocked down tinseltown doors getting his pet project made. If it hadn’t been for Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rainmaker débuting weeks earlier, Good Will Hunting would have been his first starring role. In Damon, Hollywood thought it had found its new leading man: well-built, handsome, and sharp minded. Even before Damon hit the general public consciousness, he already had Steven Spielberg’s WWII epic Saving Private Ryan in the can, as the titular soldier no less.

The problem with Hollywood’s original assessment of Damon, a miscalculation as it were, is that Damon is not a leading man. Or he isn’t the leading man in the mold Hollywood tried to shape him up to be. He wasn’t his generation’s Newman, Grant, Redford, or even Hanks. He rarely excels at playing conventional heroes, he makes a dull white-hat. Will Hunting is not a hero in the traditional sense, a man raised in the projects of Boston, an outcast turning his back against a discriminatory system. There’s an intricacy to Damon’s physicality and charisma when playing Will; the actor's body language tightens up whenever the character’s walls are raised. Will’s charisma is rooted in his anger and distrust of the world around him, his rat-a-tat speech slingshotting to whoever comes within his sights.

He’s a man who uses his intelligence to give a middle finger to the world. He’s toxic with everyone around him that tries to help him better himself. Will Hunting isn’t a hero, he’s a goon on a redemption arc. In fact, the film never fully washes its hands of this character trait, almost exonerating Hunting’s flaws in light of his clean-cut redemption

Hollywood turned a blind eye to all of these facets of Damon’s performance and tried to mold him into something he’s not. It's not a coincidence that his white-hat roles in Robert Redford’s The Legend of Bagger Vance and Billy Bob Thornton’s All the Pretty Horses became blips on his filmography. Both performances fell flat - he was dead eyed as Bagger Vance’s Rannulph Junuh, a WWI vet who seeks redemption by recapturing the art of playing golf, and he lacked the same salt-of-the-earth quality as his costar Henry Thomas to really make an impact in Thornton’s western epic. Both were primed to be Oscar bait vehicles, and both face-planted on arrival.

The fact that the industry overlooked and failed to capitalize on his Good Will Hunting leading role follow-up, Anthony Minghella’s Patricia Highsmith adaptation The Talented Mr. Ripley, is also indicative of the struggles Damon would face during the majority of his career. With the exception of the HFPA, award bodies ignored the performance, as they would for the majority of his most interesting or personal work. The industrial complex of the award circuit would spend the next twelve years waiting for the promise of their pre-emptive “Matt Damon, charismatic Leading Man” narrative to come to fruition. His mid career nominations for Clint Eastwood’s Invictus and Ridley Scott’s The Martian, read as a misrepresentation of his career, embodying the branding and not the performer, though The Martian's Mark Watney glistens with indelible charm and is the closest Damon came to the traditional leading man mold.

The strongest motif resonating throughout Damon’s filmography is his portrayal of bruised men, chewed up and spit out by the fallacy of social institutions. In Courage Under Fire, he’s chewed up and spit out following his service in the Gulf War; in Good Will Hunting, he’s chewed up and spit out by the socioeconomic landscape of Boston, Massachusetts; in The Talented Mr. Ripley, it’s the class system. In The Legend of Bagger Vance, it’s his service in WWI; in The Bourne trilogy, it’s his service to the CIA; in The Good Shepherd, it’s losing his soul by giving a lifelong dedication to the FBI. The list goes on and on. There’s also a connective tissue of Identities broken or lost, flowing through Damon’s work. What are Ripley and Doug Liman’s The Bourne Identity but two mirrored European travelogues, whose protagonists piece together their fragmented identities as they go?

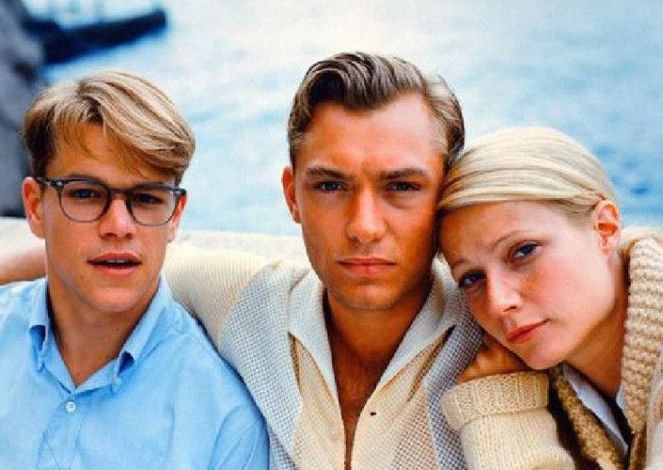

Ripley could easily be viewed as Damon’s piece de resistance, emblematic work coming right out the gate as he reached stardom. What’s so remarkable about his performance as Tom Ripley, a con artist leeching off the lives of Dickie Greenleaf (Jude Law) and Marge Sherwood (Gwyneth Paltrow), an upper class couple vacationing in 1950s Italy, is the way the actor plays on audience expectations. Tom Ripley isn’t what he seems to be, and he’s not what was expected of him. So much of Ripley's mechanism to seduce Greenleaf and Sherwood is reflected in the way the industry was selling Damon as a star. Damon’s Ripley uses this studio brand as a front of seducing his prey, selling his false earnestness and boy-next-door appeal. By using the studio branding against itself and reversing the true nature of the role, the performance became meta-contextual work, indicating that he didn’t want to be cut from the same cloth as the Hollywood leading men then came before him.

Granted, there are very valid criticisms of Damon’s performance. If anyone had to single out a sore thumb from Manghella’s tapestry of Highsmith’s world, it would be Damon. He lacks Law’s authentic presence, Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s chaotic energy and isn’t as ingrained within the story as Cate Blanchett or even Jack Devenport. The seams behind Damon’s performance are showing. It takes a lot of audience suspension of disbelief, especially during the second and third acts, where Ripley’s ruse has yet to be unveiled. There’s a transparency to Ripley’s ulterior motives that hinders the film tension.

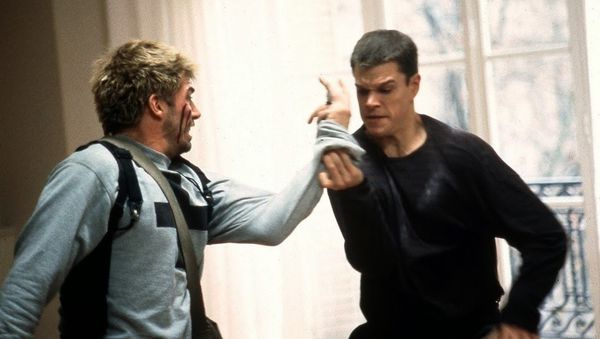

Still, there’s an interesting frailty to Damon’s performance in Ripley that doesn’t appear elsewhere in his filmography. The way Ripley hides behind his spectacles, the way every glance gives way to a sense of longing, the way that every turn of conversation is italicized. Now, there’s a difference between frailty and vulnerability. Showing the vulnerable underbelly of the male psyche is something Damon does a lot. Despite all the guns blazing, there’s a vulnerability to Jason Bourne at the center of Doug Liman’s The Bourne Identity. Damon sprinkles minute character beats throughout the multiple set pieces, never losing sight of his character: a man with no home, no history, trying to find himself. Bourne is simultaneously an all-knowing machine with superhuman qualities and a lost boy in desperate need for answers. Damon treats action sequences as character-based scenes as Bourne slowly rediscovers himself, relying on his instincts without even knowing or trusting them. The camera captures Damon as he expresses Bourne’s disbelief at the actions he’s performing so single-mindedly, the uncertainty of what he could do next. The Bourne Identity was Damon’s first top-billed tentpole vehicle. He doesn’t treat this as a paycheck, relying on the action to carry his weight. There’s no sleepwalking; he roots the material in character twofold, amplifying Bourne’s dualistic nature.

Damon would later return to portray dualistic characters when he teamed up with Martin Scorsese in The Departed. During the film’s opening montage, crime boss Frank Costello (Jack Nicholson) says directly to the camera, “When I was your age, they would say we can become cops, or criminals. Today, what I'm saying to you is this: when you're facing a loaded gun, what's the difference?” And this is the mantra Scorsese follows for the film’s remaining 2h 40 min running time. The film follows the parallel arcs of Colin Sullivan (Damon), one of Costello’s moles placed inside the Boston PD, and Billy Costigan (Leonardo DiCaprio), an undercover officer infiltrating Costello’s gang. This might be both Damon’s and DiCaprio’s finest hour, with Damon blending a mixture of notable Damon tropes stacked on top of each other in a performance that feels breathtakingly singular. DiCaprio gets the showier of the two arcs, expanding his repertoire in gritty, electric, volatile but authentic fashion, while Damon’s role is more internalized, exploring parallel story beats without breaking a sweat or raising his voice.

In classic Damon fashion, Collin Sullivan is once again a character facing an identity crisis. It also marks a homecoming of sorts for Damon, a return to his hometown of Boston and a character type he hadn’t portrayed since the late 1990s. There’s a smug and entitled thorniness to Sullivan, where Damon uses his fratboy rat-a-tat energy usually reserved for his Kevin Smith collaborations, to great effect. In an ensemble, where DiCaprio, Nicholson, and Mark Wahlberg are firing on all cylinders, there’s a modesty to Damon’s performance, as if Sullivan is keeping all of his demons close to the chest.

There’s a richness to Damon’s portrayal of a duplicitous soul with two masters. And possibly apart from his work in the Bourne series, Damon has never been more in control of his physicality as a performer. Using his muscle mass to deflect and eternalize the self-doubt and fear consuming his character. He shifts his body language when Sullivan romances Madolyn (Vera Farmiga) the precinct’s shrink. He’s less imposing and rigid, bringing forth a faux-casualness that reads as insincere. There’s a dark underbelly to the way Damon flexes the boyish charm of his youth, offering hollow pleasantries and modesty while he manipulates those around him. The performance reaches a fever pitch in the third act, where following the death of Captain Queenan (Martin Sheen), Sullivan goes toe-to-toe with Sgt. Dignam (Wahlberg) during a boardroom brawl. In volcanic fashion, all of the compounded externalization Damon stored throughout his performance erupts, leaving Sullivan emotionally naked and wounded. It’s the character’s most destructive state, almost giving himself away, but also his most vulnerable state.

In a larger sense, Colin Sullivan feels like the spiritual offspring of both Will Hunting and Tom Ripley, with Damon coming full circle. Much like Hunting, Sullivan uses his authority as a means of giving the middle finger to the world. And like Ripley, Sullivan has a callousness to his duplicity. Again, Sullivan is a character branded as one thing, while being something completely different. The role is the natural progression of Damon’s career circa 2006, capitalizing on the thornier aspects of his persona, fully embracing his role as the slimy anti-hero that defined the first half of his career.

more on The Departed

more on The Talented Mr Ripley