by Nathaniel R

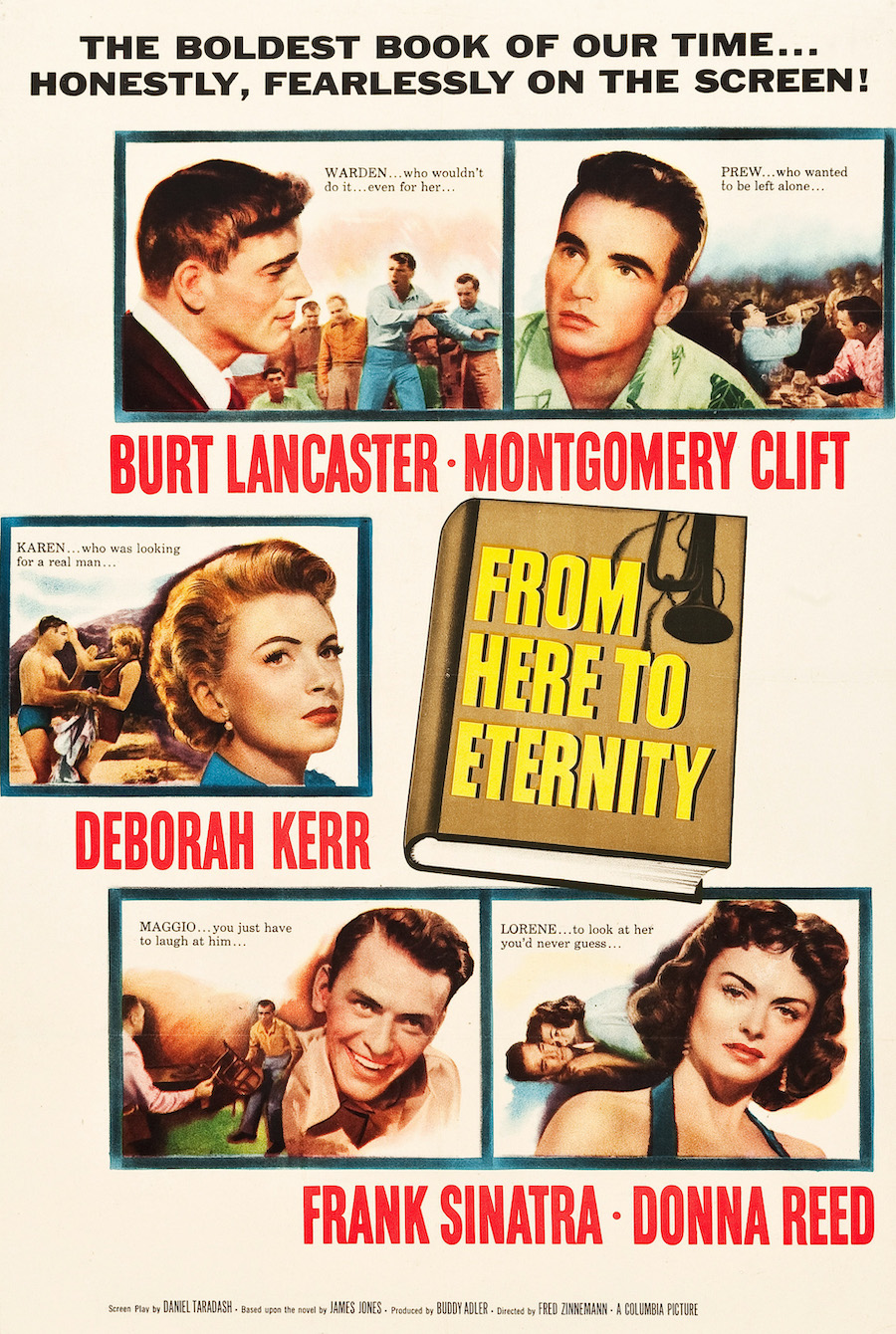

Calling your picture From Here To Eternity, even if that's the name of the book its based on, is a major flex and a tempting of fate. How to live up to the title? 1950s and 1960s movies did this frequently, of course, in their battle against the looming threat of television. Screens got bigger and wider and the studio system was, if already mortally wounded, still working hard at making their movie stars iconic. Titles like Giant, The Greatest Story Ever Told, The Greatest Show on Earth, frequently dared to proclaim their epic-ness, and if the titles weren't size-conscious, why not add an exclamation point a la Oliver!, Hello, Dolly!, Viva Zapata! or I Want To Live! In this lust for enormous movies, From Here To Eternity stands out, not just for living up to its promise and being eminently swoon-worthy but for its relative modesty -- capturing something grandiose merely by inhabiting the sealed world and social lives of soldiers and their women on the brink of cataclysmic change. It might have been mere soap opera without the skillful direction of Fred Zinneman and the simple fact that the stars themselves were monumental.

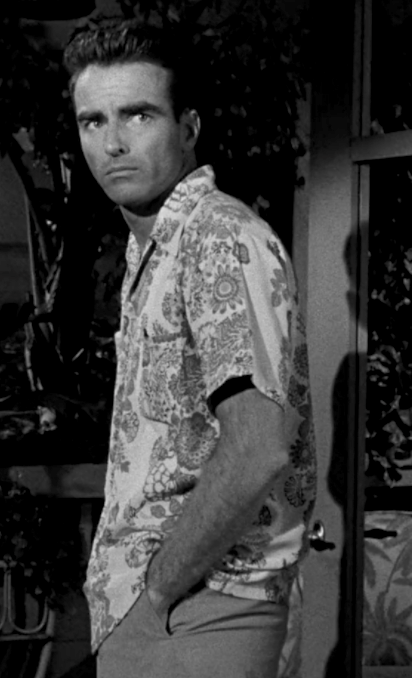

Chief among them was Montgomery Clift, scoring his third Best Actor nomination with his eighth film...

Private Robert Lee Prewitt (Montgomery Clift) is the first character we meet in the ensemble picture, positioning Clift as the focal point of the ensemble, though the other characters follow in short succession. Prewitt befriends a happy-go-lucky fellow soldier (Frank Sinatra in his Oscar-winning role), and a Corporal (Jack Warden), romances a local "social club" worker (Donna Reed in her Oscar-winning role), makes enemies of the Captain (Philip Ober) and another soldier (Ernest Borgnine) and faces off with an ambitious Sergeant (Burt Lancaster), who is romancing the Captain's wife (Deborah Kerr). The collision of all of the characters portrayed by invested charismatic actors, in fluctuating moods of anger, horniness, bloodlust, friendship, respect, drunkeness, shame, and pride, give the movie its plentiful sparks. In the context of Clift's career, and as the definitive peak of his popularity, it holds a special fascination.

The very first time audiences saw Clift he was in military uniform in a contemporary picture set in post war Germany for The Search (1948) where he quickly returned for The Big Lift (1950). His third time in uniform, we're in pre-war Hawaii shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The military is fertile ground for Clift's ever-fascinating and perpetually tense star persona. Even outside of military pictures, as in Red River (1948) or A Place in the Sun (1951) he's othered... a 'different' kind of man at odds with expectations of what men should be in those environments; one shouldn't always read 'queer' though that's fun, too. In the all-male environment of the military, this conflict isn't subtext. Indeed, it's the primary conflict of his half of From Here To Eternity. Prewitt is immediately pissing other men off by betraying the natural order, if you will, and staying true to himself alone.

I can't figure him.

Sergeant Warden (Lancaster, terrific) calls him a "hard head" and they warily circle each other, with lots of staring. Prewitt and Warden don't understand each both but mutual respect begins to take hold. Others aren't so flexible and immediately dislike him. The Captain is deeply annoyed that he's a "lone wolf" and the boxing team at the base is thoroughly pissed off that someone who is a good fighter refuses to join their ranks. Prewitt is a contradiction, a life-long soldier who refuses violence, and many of his peers aren't having it.

The Captain and a group of the other soldiers conspire to make life difficult for him. Ostensibly they want to teach Prewitt a lesson about insubordination. In actuality, it's a punishment for his refusal to be the man they want him to be. He's subjected to months of grueling menial tasks which prove an inadvertently kind way to give us beefcake shots of the movie star. This is not an accident because one of the most honest things about From Here to Eternity is its horniness for its stars (who are also horny for each other) whether its Donna Reed in tight gowns, or Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr's rightfully famous and incredibly sexy roll in the sand.

Lancaster and Kerr make for a sizzling onscreen couple (both were Oscar-nominated) but Eternity doesn't leave Clift out of its carnal equation.

While it's fun to do queer readings of the filmographies of gay stars, it's not always entirely satisfying. This 1953 Best Picture winner is often discussed for its ambiguous male eroticism (both Lancaster and Clift are displayed for our pleasure, but only Clift is displayed this way without the context of a woman gazing at him along with us). Neverthless queer readings of From Here to Eternity too easily shrug off the matter of Alma/Lurene. Prewitt may be a 'different' kind of man, but there's a believably sexual charge to his scenes with Donna Reed that is closer to heternormative than Clift's previous onscreen romances. Here the female star is displayed and Clift, for his part, can't take his eyes off her. Alma and Prewitt's budding romance is nowhere close to the idealized heightened swoon he and fast friend Elizabeth Taylor conjured so unforgettably in A Place in the Sun but, like the Lancaster/Kerr union if to a much lesser extent, it feels rooted in actual rutting, or the potential of it.

Though Taylor will always be his definitive female co-star, Clift has wonderful moments with Donna Reed, both in their mutual flirtations and in their less pleasant moments including snappy disagreements, drunken episodes, and the outsized possessiveness that erupts quite suddenly and moodily from Prewitt. Clift also gets monologues in his scenes with Reed that the military scenes don't allow. The first is a very well executed speech about why he gave up fighting that the actor obsessed over and surprisingly underplays given his reportedly painstaking preparation. He's alive with Reed (and also with Frank Sinatra to be fair) in a way that seems more relaxed than he often appears onscreen but is still firmly rooted in this character.

And what a character Prewitt is. Or, rather, what a meal Clift makes of him Prewitt on the page has solid potential but might have been monotonous or simplified with a lesser actor. Consider the slyly performative quality Clift grants Prewitt's stubborness, for one.

This man isn't just defiant to be true to himself, but because he enjoys it. Or watch the tiny glimpses Clift allows us of the different gentler man Prewitt might have been outside of the military as with the the sudden passionate trumpet playing or the aforementioned monologue. In his second monologue there's even the suggestion that, for all his surety of self, he's maybe too self-deluded or masochistic about his place in the military. Prewitt gave Clift the committed actor a lot to work with and he rewarded the film with one of his very best performances.

The role also proved definitive to the actor's legacy.

As with the troubled soldiers and angry women onscreen, who are all unaware that their lives are about to violently change, tragedy would soon strike Clift offscreen. It would be four long years before Clift returned to movie screens, sealing From Here To Eternity in cultural history as the peak of both his stardom and beauty. The movie would prove to be Clift's all time biggest box-office hit, and win 8 Oscars including Best Picture. Despite his contributions to its enormous success, Clift would walk away empty-handed, again, a bonafide acting legend underappreciated in his time and even to this day. But as Prewitt himself would say over drinks, "a man loves a thing, that don't mean it's gotta love him back."

To the memory of Robert E Lee Prewitt.