"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

The Last Emperor is enormous, as is its reputation. The shorter version is nearly three hours long. It swept the 1987 Oscars, winning all nine categories in which it was nominated. Its plot tracks events of global significance, across nearly six decades of Chinese history. The production required more than 10,000 costumes and 19,000 extras, many of them recruited from the People’s Liberation Army

The Last Emperor is enormous, as is its reputation. The shorter version is nearly three hours long. It swept the 1987 Oscars, winning all nine categories in which it was nominated. Its plot tracks events of global significance, across nearly six decades of Chinese history. The production required more than 10,000 costumes and 19,000 extras, many of them recruited from the People’s Liberation Army

But beyond its stature as a film, it is also something of an act of economic diplomacy. China, which had heavily restricted tourism before the late-1970s, began a major about-face with Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 “Reform and Opening Up” program. Part of this effort included the promotion of heritage tourism. China ratified the World Heritage Convention in 1985, and added its first six World Heritage Sites in 1987. The Forbidden City was at the top of the list.

It’s not a coincidence that Bernardo Bertolucci was granted permission to film in the Forbidden City right at this time, the very first Western production allowed through the palace gates...

The Last Emperor doubles as a massive promotional campaign. And it’s hard to imagine a more successful advertisement than a Best Picture-winning film.

Still, if The Last Emperor were only a promotional video, it wouldn’t be worth revisiting today. It’s both overwhelming and sparse, opulent and desolate. By the time Puyi was crowned Emperor in 1908, at the age of two, the Forbidden City was nearly 500 years old. Three years later, the monarchy was overthrown. But Puyi remained, to grow up a living tomb of his empire. By modulating brilliantly between opulence and restraint, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti (and his team) perfectly captured the bizarre contradictions of this moment.

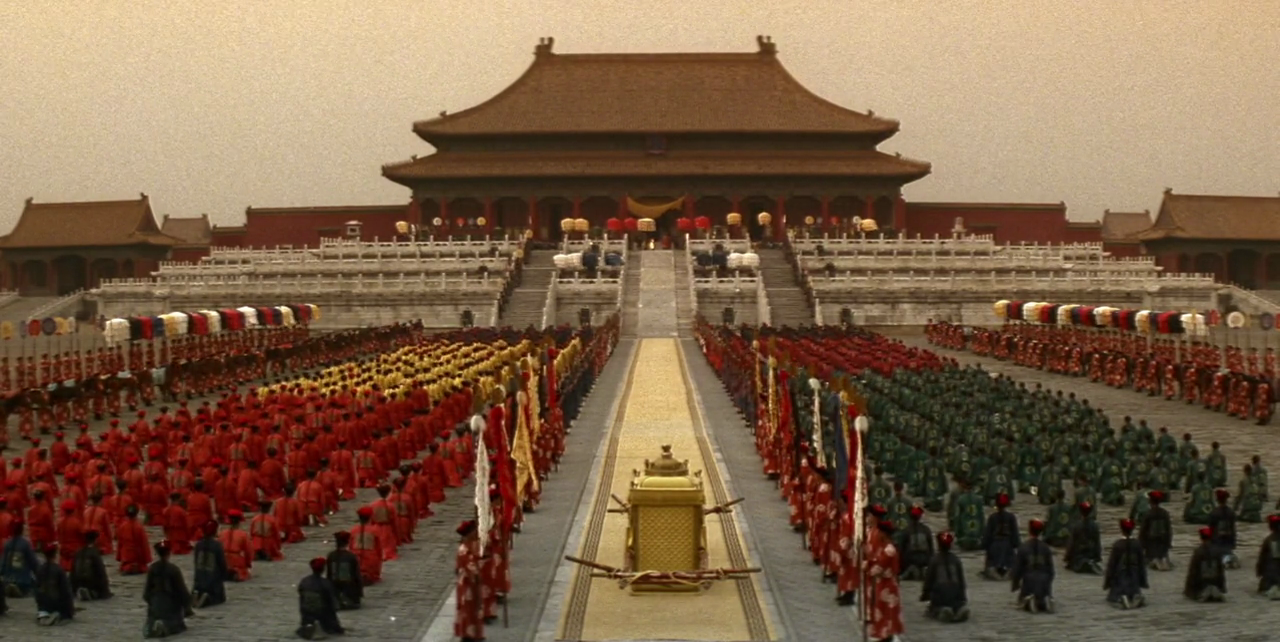

They accomplished this, in part, by playing very effectively with the enormity of the Forbidden City’s open spaces. The most impressive sequence is Puyi’s coronation, in which thousands of extras kowtow to the child-emperor in the grand plaza.

Just a few scenes later, Puyi runs around the mostly-empty courtyard with his brother. A small army of eunuchs chases after them, palace employees whose entire livelihood is based upon the daily schedule of a toddler.

The architecture is consistently breathtaking, of course. But it is also remarkably malleable from the perspective of a filmmaker, an enormous canvas. The colorful crowds of the coronation scene bring the Forbidden City to life. Without them, it offers a relatively simple color palette and a vast quantity of negative space.

Bertolucci also makes great use of the palace’s many passageways. Puyi sprints down the unadorned alleys, empty spaces between the Forbidden City’s (rumored) 9,999 rooms and the outside world.

The exterior shots are authentic, as well as the few scenes in the Hall of Supreme Harmony - the throne room at the top of the steps. All of the other palace interiors were recreated in studios, either in Beijing or at Cinecittà in Rome. (This means that the nearly 2 million artifacts in the Palace Museum’s collection do not appear in The Last Emperor).

Storaro and Scarfiotti’s approach to the interiors combined months of research into Chinese decorative art with an almost monochromatic approach to color. The death of Dowager Empress Cixi (Lisa Lu) is a great example. Her room is densely packed with both sculptures and living observers, all focusing their attention on the Empress’s wheeled platform. One can recognize reds and golds, intricate details carved all across the room, but the overall atmosphere is one of bronzed dust.

Puyi’s marriage chamber, years later, is similarly engulfed by a single mood. The room practically swallows the now-teen emperor (Wu Tao) and the new Empress Wanrong (Joan Chen). It seems to suggest that their wedding, despite involving them personally, is much more significant as an image and as a tradition than as a union of two people. Despite its decay, it is the Forbidden City itself that grants meaning to their relationship.

And perhaps this is why harmony between them is impossible after their banishment in 1924. By this point, the eunuchs have been thrown out and the palace feels even more emptier. The eviction notice arrives in the midst of a cricket game, the adult Puyi (John Lone) having been aggressively anglicized by his tutor (Peter O’Toole).

It’s the most surreal use of the palace yet, a scene that seems to rob the Forbidden City of its splendor. The camera is mostly pointed away from the Hall of Supreme Harmony, focusing instead on the newly-painted cricket ground. The intricately carved rows of white steps now resemble bleachers. There is no more majesty here.

The palace was turned into a museum almost immediately after his eviction, opening to the public in 1925. Its furnishings and artifacts were removed during the war and returned in its aftermath, though a couple thousand boxes wound up in the National Museum in Taipei.

Decades pass before Bertolucci’s Puyi sees this courtyard again. In the 1960’s, rehabilitated as a gardener by the Communists and finally released from prison, we see him return to the Forbidden City as a visitor.

Puyi makes his way into the square and toward the Hall of Supreme Harmony, in which the Dragon Throne is now roped off. And after a short scene with the young son of the groundskeeper, Puyi disappears. It is as if he has become yet another object in the collection, to be filed away in his box in the archives at long last. We, in the audience, are invited to see things from the perspective of the little boy, the unsuspecting witness of a mystery. And, of course, to hop on a plane and see it ourselves.