Carl Theodor Dreyer is one of my favorite filmmakers. I'll never forget the first time I watched The Passion of Joan of Arc on the big screen and was transported, how experiencing Vampyr felt like witnessing a projected nightmare, the ecstasy of Ordet's ending or Gertrud's stern ruminations on love. It's to my great shame that I'm not familiar with the Danish director's early works, having mostly ignored them until now. The centennial of Dreyer's second feature, Leaves from Satan's Book, makes this a great time to start correcting these cinephilic lacunas…

Released in 1920, Leaves from Satan's Book, originally titled Blade af Satans bog, is a collection of four stories about devilish temptation, human vices, and eternal damnation. The Devil is our main character, the viewer's guide through these sorry tales. First, Lucifer presents us with the matter of Judas and his betrayal of Christ. The famous traitor is seen more as an idealist misguidedly fighting for his cause than a mean schemer. The following chapter jumps ahead to the time of the Inquisition, when, in the guise of a priest, Satan influences a monk to rape a beautiful woman. Then we're off to the French Revolution when the longest stretch of the narrative unfolds.

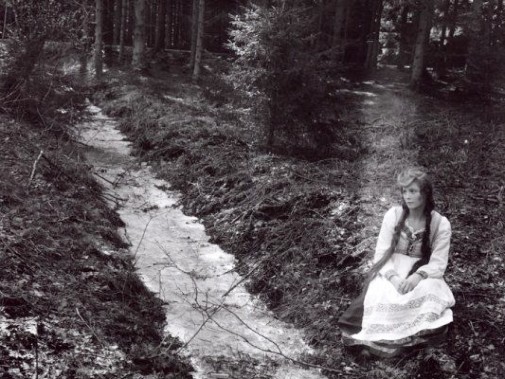

Framing the story around Marie Antoinette's trial and execution, Lucifer assumes the form of a revolutionary intent on driving a youth to betray the doomed queen. Finally, Leaves from Satan's Book arrives in the 20th century with the tragedy of a Norwegian woman victimized by the treacherous Red army. Throughout it all, Dreyer makes the peculiar choice to empathize with his hellish protagonist. In the filmmaker's vision, Satan emerges as a fallen angel whose tempting ways are tortuous labor. For every soul they fail to corrupt, the eternal being wins centuries of freedom from God's punishment. In many ways, they want to fail and resent all those who choose the path of evil.

In this tricky central role, Helge Nissen delivers the picture's best performance, highlighting Satan's odd humanity, their frustrations, and even their pity. At the end of this miniature tetralogy, one might find themselves sympathizing with Satan, and looking at God as a cruel entity. Several times, when the fallen angel wants to quit, to waver on his perfidious ways, the voice from above reminds them to continue to seed evil in the hearts of Men. Perhaps you won't be surprised to know that many religious folks objected to the picture, though, curiously enough, it wasn't the portrayal of Satan that offended them.

Instead, it was the presence of Christ on-screen that caused polemic. Dreyer, who long dreamed of filming the life of Jesus, wanted to dramatize the messiah as a human, first and foremost, grounding the iconography in the frailty of personhood. The Kristelig Dagblad decried the film as an act of sacrilege, while a writer from Landmandstidende said this about the matter: "As a sleepwalker, a dreamer, Christ was portrayed, and his apostles were made out to be a flock of fatuous, inferior individuals."

They weren't the only people to see amoral and unethical behavior crystallized in the picture's essence. Labor organizations criticized Dreyer's portrayal of revolutionaries as criminal vermin, having Satan mingle with both the Jacobins and the Red Army while painting their victims as martyred saints. Even if one doesn't hold leftist beliefs, these criticisms highlight the dramatic imbalance in the script by Edgar Høyer.

In the first two episodes, one sees a mirroring happening, as if history twisted one era's victims into another time's villains. Christendom, embodied by Jesus and his faithful disciples, is wronged by Judas and the Devil's temptation. In the following piece, however, it's Christ's church that serves as a breeding ground for malevolence. Lucifer takes the form of a High Inquisitor, after all. There's no such canny inversion in the last two chapters, making them come off as repetitive. The situation only worsens when considering the imbalances in length from one episode to the next. The French Revolution story is long enough to be a feature.

That last bit may be due to that tale's over-reliance on written text. As a fan of silent cinema, I have long held antipathy for movies that include too many intertitles, depending on verbiage to drive the narrative rather than the moving image. While the script is likely to blame for such failures, Dreyer's direction doesn't always help. His pictures are always beautiful, but his mise-en-scène feels immature when compared to his later works. One sees the inklings of oncoming minimalism in the set design, but the blocking of actors feels chained to stage paradigms instead of cinematic innovation.

All that said, there are many moments of breathtaking cinema in Leaves from Satan's Book. Jesus' humanity heralds a precedent for Pasolini's Gospel, while the preparations for Marie Antoinette's execution glow with fatalistic dread and an odd serenity. No one is born a master, and even geniuses like Dreyer have to perfect their art before they dazzle the world with faultless miracles. The Passion of Joan of Arc wouldn't exist without Leaves from Satan's Book. Because of that, I'll always be thankful for this century-old picture.