"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

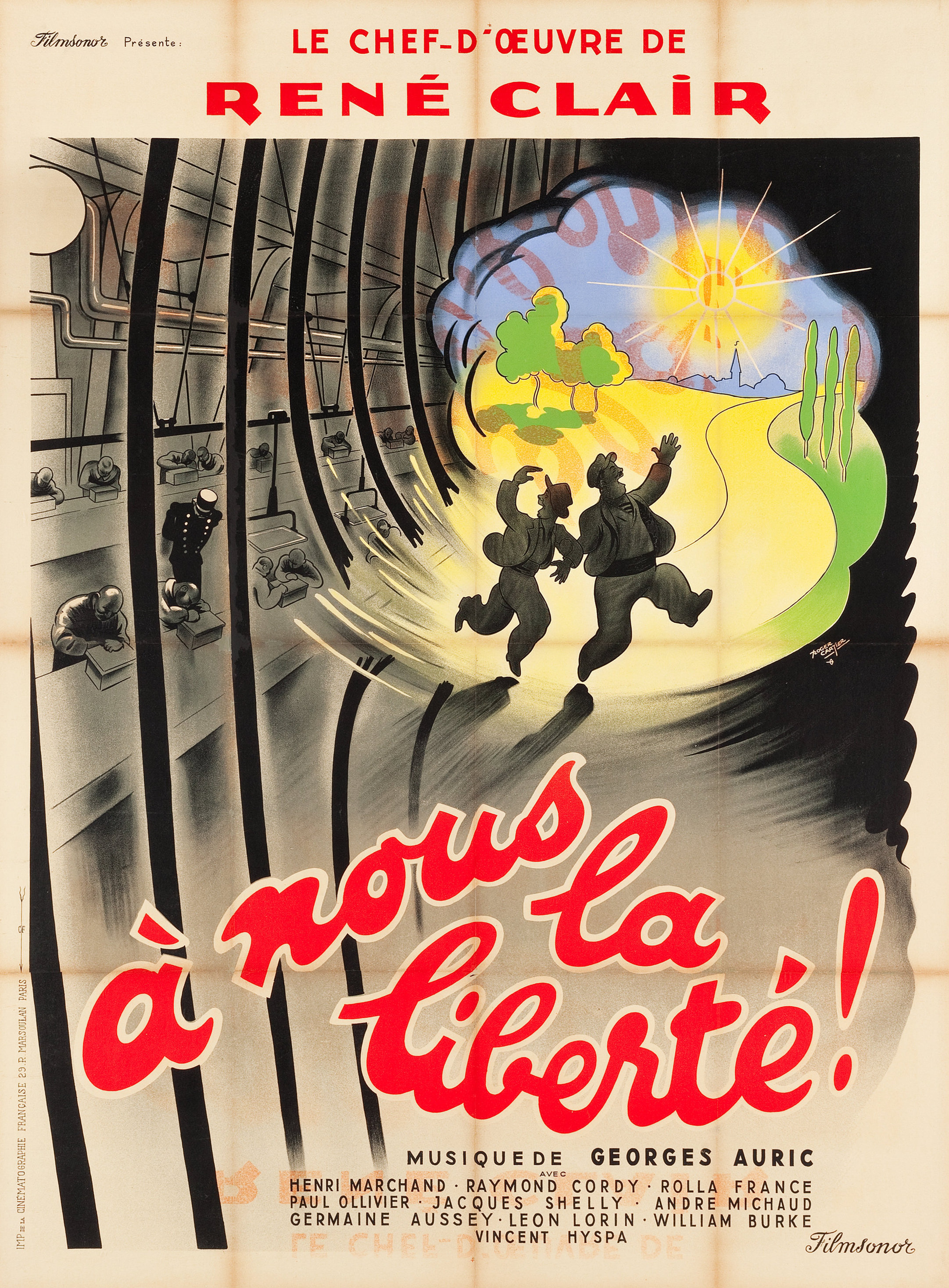

Once upon a time, the Oscars were in November! Well, thrice upon a time. The 3rd, 4th and 5th Academy Awards were held in the fall - the last of them on November 18th, 1932. Nathaniel covreed the biggest piece of trivia from that night earlier this morning. But there were also a few firsts, including the debut of the short film categories and the first-ever foreign-language nominee. René Clair’s À nous la liberté was nominated for Best Art Direction, an award it lost to a cruise ship comedy called Transatlantic.

Once upon a time, the Oscars were in November! Well, thrice upon a time. The 3rd, 4th and 5th Academy Awards were held in the fall - the last of them on November 18th, 1932. Nathaniel covreed the biggest piece of trivia from that night earlier this morning. But there were also a few firsts, including the debut of the short film categories and the first-ever foreign-language nominee. René Clair’s À nous la liberté was nominated for Best Art Direction, an award it lost to a cruise ship comedy called Transatlantic.

But it’s Clair and art director Lazare Meerson who have the last laugh, as their losing film is now largely regarded as a classic and Transatlantic barely has a Wikipedia page. A nous la liberte is a charming little oddity, a musical comedy about the alienation inherent in modern industry. It opens in a prison, where cellmates Émile (Henri Marchand) and Louis (Raymond Cordy) are at work hand-carving toy horses. The cavernous space evokes the ominous architecture of the modern prison, its high balconies a reminder of constant surveillance...

The mess hall is essentially the same, Meerson’s sets constantly suggesting even more patrolling eyes than we can see in the foreground.

That night, Émile and Louis attempt to make a break for it. The walls of the prison are imposing and bare, with an almost theatrical simplicity.

Louis escapes, Émile does not. Time passes, a montage showing Louis’s rise in fortune from a lowly record salesman to captain of industry. When Émile is finally released, he stumbles into a job in a grand record factory, unaware that it’s owned by his old friend.

Remind you of something? The overall point of the production design is a simple one: the assembly line is dehumanizing, in much the same way as a prison. The film’s opening sequence echoes even more clearly in the factory’s mess hall, which has its own conveyor belt.

And how does one get a job in this factory? Well, there’s not so much an application process as an industrial/medical screening. Batches of job seekers enter the office and are directed to speak directly into microphones, where they report their name and age. Then they turn around to be weighed. Presumably this sorts the men based on which assembly line is best suited to their body-type.

Is it subtle? Absolutely not! But Meerson’s visual language is as charming as it is striking, quite effectively complementing Georges Auric’s bright and jaunty score. It’s no small achievement. The sets are surprising and dynamic enough to promote lightness and humor, while simultaneously stark and impersonal enough to underline the faceless inhumanity of the factory.

One could even argue that Meerson’s work was so successful, it holds the blame for the bizarre legal battle that followed.

In 1936, five years later, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times was released. Tobis Film, the German production and distribution company that financed À nous la liberté, launched a plagiarism suit against Chaplin. Clair, for his part, was horrified by the decision and very publicly stated that he considered it an honor to have inspired Chaplin, one of his great heroes. And many have assumed that Tobis’s lawsuit was little more than a legally spurious attempt by Nazi Germany to take a potshot at Chaplin.

United Artists, for their part, argued (pretty convincingly) that no one who worked on Modern Times had even seen À nous la liberté. Which leaves us with a delightful irony. The two films were each so successful in charmingly representing the inhumanity of industrialization, that they wound up looking quite a bit alike.

At the end of À nous la liberté, the workers are saved by automation - something that may seem bizarre today, when we often think of automation as increasing unemployment. Here, in this bright alternative vision, more machines have simply given the laborers a whole lot more free time. And so, with a couple workers keeping a relaxed eye on the machines, everyone else can go fishing. It is, at long last, a giddy freedom from design.