Few cineastes can count their last film among their greatest works. Fewer still finish a career, a life, with their best cinematic effort. As much as I admire such gems as Ophüls' carnivalesque Lola Montès, the amorous musings of Dreyer's Gertrud, the bittersweet self-reflections of Akerman's No Home Movie and Varda's Varda by Agnès, I wouldn't classify any of those pictures as their director's crown jewels. John Huston's a whole different matter.

The American filmmaker, whose career spanned six decades, finished his last picture in 1987. Faithfully adapted from a short story by James Joyce, The Dead may not be as influential as The Maltese Falcon, as exciting as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, nor as tragic as The Misfits, but, as far as I'm concerned, it's Huston's most ravishing creation…

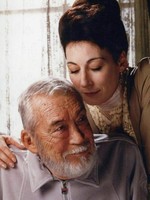

The Dead was a passion project for John Huston. He was dying through most of its making and knew it too, as did his children. Son Tony Huston wrote the screenplay for the flick and worked as an assistant director, aiding the patriarch who was succumbing to emphysema and cardiac issues. Anjelica Huston, who had won her Oscar for John's previous picture, Prizzi's Honor, was also on set, playing the role of Gretta Conroy and delivering her most luminous performance.

Set in a snowy night of December 1904, The Dead is a shockingly simple affair, devoid of outward conflict or any hint of bombast. Its humble story concerns a holiday party being thrown by the elderly Morkan sisters and their devoted niece, all of whom have dedicated their lives to the performance of music as well as its teaching. Among the guests are family and professional acquaintances, longtime friends, and newfound companions who partake in an evening of shared joy and sauce-less roast goose.

The action nearly unfolds in real-time, only using the abbreviating power of cinema editing once or twice. Through the evening, our eyes and ears are drawn to different people, basking in the warm glow of their humanity. From the charm of a drunken guest to the poetic recitations of a splendid orator, there's much to admire about this congregation and Huston is generous towards them all.

Many moments of the party draw a tear or two from my eyes, but I'd like to highlight one particular scene of serene transcendence.

As a former choir singer's aged voice bellows a tune by Bellini, the image floats through the house, abandoning the Dubliners and finding the objects that materialize ghosts of their past. Pictures on the wall, yellowed embroidery framed like relics, winter coats resting on a crochet bedcover, trinkets of long lives nearing its end. It's beautiful, melancholia summarized in the glide of the movie camera and soft fades. Elegiac and modest, all the more powerful for how simple it is.

A tinge of sadness shades the merriment, but there's also happiness blossoming from the sorrow. The ephemerous nature of life is subtly expressed in Huston's observations, but his conclusions aren't steeped in misery. Our existence might have an end, but it's beautiful while it lasts. Whether long and rich or short and despondent, human life is to be treasured. The same is true of the imagination and the emotion of the mind and the heart. In the end, all of these are things so wondrous they're beyond comprehension. So fragile too.

When the night reaches its end, and the Conroys are leaving to go back to their hotel room, Anjelica Huston's Greta is stopped on her way down the stairs. A song laced with painful memory comes floating down from above and, for the duration of the melody, no one moves. Quietness rules over the scene, and the actors' faces dominate the frame. A single tear shines with all the deep meaning contained in Joyce's prose. For a moment, it's as if the world stands still, on and off-screen.

The Dead reaches its ending at the Conroys' room when Gretta explains her reaction to the music. I won't spoil the sad tale she tells but be assured it's as beautiful as anything that's ever been recorded on celluloid. Our eyes become Greta's husband's eyes as he sees her, perhaps for the first time. Illuminated by moonglow, the actress' face is a monument, a blessing, a miracle. Both Hustons, in front and behind the camera, handle the scene with delicateness, as if its spell could be broken with a misplaced whisper.

Many would call The Dead too small to be worthy of this praise, but there's spellbinding rigor to its construction. A lifetime of experience informs the director's every choice, his audiovisual language perfected to the point of poetic minimalism. As gentle as a kiss from a snowflake, as warm as a holiday meal, as inebriating as strong port, The Dead is a perfect film, the kind which makes one believe that there might indeed be some otherworldly magic to this seventh art.