By: Patrick Gratton

Canadian history remembers William Lyon Mackenzie King as one of our most defining statesmen. King was the longest running Prime Minister to hold office in Ottawa, and a central ally to both Winston Churchill and FDR, in mobilizing Canada in World War II. Historians commend Mackenzie King as a central rallying cry for a divided country, whose skill set helped him reach across the aisle, mending multiple differences and helping grow Canada’s Independence even as it remained a British colony.

In his feature film debut The Twentieth Century, Winnipeg-born Matthew Rankin subverts this story. Set in 1899 and told in ten chapters, the film omits all of the soon-to-be Prime Minister’s triumphs, focusing instead on Mackenzie King’s (Dan Bierne) candidacy to be the country’s leader. Rankins shows a steady hand, confidently orchestrating a film that’s equal parts German expressionism, 1920s melodrama and absurdist satire. The film unapologetically ransacks the mythos of the Canadian identity.

The future prime minister is depicted as a precious man-child, with an overbearing mother (Louis Negin, in drag)...

She has long ingrained into her son the prophecy that he’s destined to become Prime Minister, succeeding the tyrannical dictator Lord Muto (Sean Cullen). The prophecy also includes marrying a woman with golden locks, who just happens to be the splitting image of Muto’s daughter, Lady Ruby (Catherine St.-Laurent). The electoral race for Prime Minister isn't defined by political rallies or democratic norms, but determined by a series of Voyageur games styled competition with events such as subtle passive-aggressiveness, snow-bank urination, and leg wrestling.

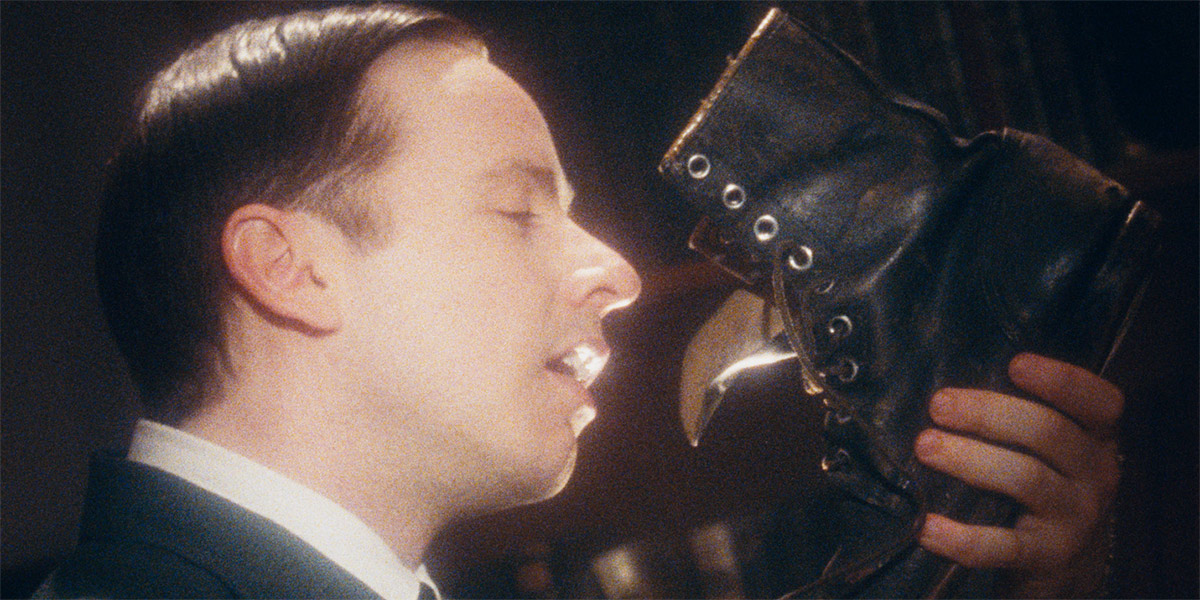

Mackenzie King eventually loses both the title of Prime Minister and Lady Ruby’s hand, sparking a series of events where he fails upwards in the echelon of the Canadian political sphere. The Twentieth Century has a keen eye for the absurd and the perverse, tearing through the densest of plotting in a mile-a-minute fashion. We can't even get into Mackenzie King’s boot-sniffing fetish, his chronic masturbation, The Boer War, separatist groups, orgasmic cactuses, evil maniacal doctors or even the film’s surprisingly earnest romance between Mackenzie King and Nurse Lapointe (Sarianne Cormier), his mother’s former chambermaid.

Bierne’s performance juxtaposes absurdism and earnestness and he grounds his character in hopeful, if not totally dim, aspirations. Bierne neither under or oversells King’s abilities and ideologies, or let's him fall into idiot savant tropes. Sure, King makes for a farcical protagonist, but Bierne never plays the character strictly for laughs; there’s a dignity to the performance even when the character fails. As his love interest, Sarianne Cormier helps form the film’s beating heart. She’s constantly in sync with the film’s ever-adapting wavelength, pouring joy and heart into a role that could have been an easy punchline. Together the central couple are a sobering center, to a Monty Python-esque ensemble of broad caricatures surrounding them. The best of which, is Comedian Sean Cullen, who while lovingly bombastic as Lord Motto, never forgets to deploy the necessary menace to make the tyrant work.

King constantly grappling with himself and his place in his world, reads as both a product and an indictment of the current day Canadian identity. The Twentieth Century is clearly of the Trudeau II era. It’s impossible not to read the film’s depiction of King, a duplicitous man who one seconds visits orphans promising to illegalize tuberculosis, only to forget said promise the next, as an analogue of Trudeau himself. Both men share a similar political narrative: Stories of self-entitled men rising through the ranks under the umbrella of populism, the geniality of hopefulness and empty promises. In politics, it’s almost impossible to meet the standards of your ideological self. Yet, for us Canadians, the whiplash caused by the discrepancy between the man on the trail and the man running Parliament, led to a national sentiment of resigned resentment.

Rankin’s paints a rather bleak portrayal of the Canadian identity. During the commencement ceremony for the Prime Minister competition, the candidates recite the following creed “May the Disappointment keep us safe from foolish aspirations and unreasonable longing, do more than is your duty, but expect less than is your right.” In Ranking’s retelling of Canadian mythos, we are not viewed not as a level-headed peacekeeping people but as strawmen depleted amongst a world of strongmen. It takes a lot out of us to be your northern neighbors. We cave to unruly governance, because we’re discouraged to strive for better ones. The theme of the Canadian Identity as one of disappointment is sprinkled throughout the film. In an era, where the adoration of one’s National flag is frequently politicized, the Canadian Flag is not viewed as the embodiment of national pride, but referred to as The Disappointment. Likewise, provincial legislator buildings are named disappointment squares.

The spectre of Guy Maddin, Winnipeg's leading auteur, looms heavily over The Twentieth Century. Rankin’s adoration for the house of Maddin, is both the film’s strongest asset and biggest drawback. Where the worlds of Maddin‘s cinema feels insular, taking place in the abstract neurons of his psyche, The Twentieth Century surpasses this, grounding itself in its narrative and its production design of Canadian geography. There’s an arch pristineness to Rankin’s winterized metropolises. Montreal is an idealized winter wonderland blistering with hope and Toronto is a German Expressionist ice fortress, with its arched roads and walkways. Elsewhere, he depicts Winnipeg as the mud-infested Wholesale city lodged between the inner circles of hell and British Columbia as a forestial gravesite due to Canada's industrial expansion.

But sometimes the comparisons aren't flattering. Rankin too often uses Maddin's motifs (rear projection visual effects, kitschy camp, Academy Aperture Aspect ratio, etcetera) as a crutch, borrowed and stitched together. The narrative cas gets lost at sea between imitation, political parody, and absurdist humor. Though a third act dinner party scene is so outrageous it needs to be seen to be believed, it takes the wind out of the film's sails. The third act doubling down on the perverse feels counterintuitive to the film’s first act, which is at its sharpest and most assured, when The Twentieth Century is playing like a tongue-in-cheek parody of the “great man” biopic narrative.

Still, Rankin’s own editing and Vincent Biron’s camerawork transports audiences into a kaleidoscopic phantasialand, where the past and the future meld in a single vision. It transposes the arithmetic of 1920s melodrama to the modern era, with modern ideas. This isn't reductive pastiche filmmaking. There’s a final action set piece that’s simply invigorating. Rankin’s film is blistering with hope, even when it lampoons its characters. As Mackenzie King self-proclaims, he is “worth more than the sum of his mistakes”, and bright light at the end of the tunnel is as “sure as a winter’s day in springtime”. B

The Twentieth Century is currently available to rent online.