"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

This week marks the 75th anniversary of Leave Her to Heaven, a technicolor noir blockbuster with set decoration so opulent, you will find yourself shouting at the upholstery.

This week marks the 75th anniversary of Leave Her to Heaven, a technicolor noir blockbuster with set decoration so opulent, you will find yourself shouting at the upholstery.

It has other virtues, of course: Gene Tierney’s wickedly genre-shifting performance, Leon Shamroy’s shadow-wielding cinematography, Vincent Price’s height, etc. But the last time I watched it, I couldn’t take my eyes off the sets. The film takes place in a fever-dream of post-war prosperity before the fact, an endless parade of over-decorated vacation homes.

Frankly, it should have won the Oscar for Best Art Direction - Interior Decoration, Color...

It lost to Frenchman’s Creek, a perfectly fine pirate movie that had the advantage of being an expensive period piece. But it’s a decision that looks absurd in retrospect - as does The Picture of Dorian Grey’s loss in Best Art Direction - Interior Decoration Black & White.

The two films are twinned, in a way, Janus heads facing opposite directions in time with similar dread. They both depict entirely self-contained worlds of wealth and leisure, Olympian museums of decorative art that inevitably shatter at the hands of their coolly amoral and willfully ambitious protagonists.

Anyway, time to gawk. Ellen (Tierney) and Richard (Cornel Wilde) first meet en route to a New Mexico resort, in a train car that seems impossibly lush to anyone who has ridden Amtrak in the last few decades.

And yet, all things considered, it might be the most understated set in the film. Their Taos resort is decorated to an inch of its life, mostly with plants.

The ceilings are high, but it still feels as if the characters have no room to breathe. The multiplying shadows, dim colors and crowded decor work against the facts of architecture to make everything feel claustrophobic, a remarkable achievement of cinematography and production design. It helps that some of the cacti are taller than the people.

The result is a resort that feels like a trap under the sand, Ellen playing the part of a desert tarantula - or WASP, as the case may be.

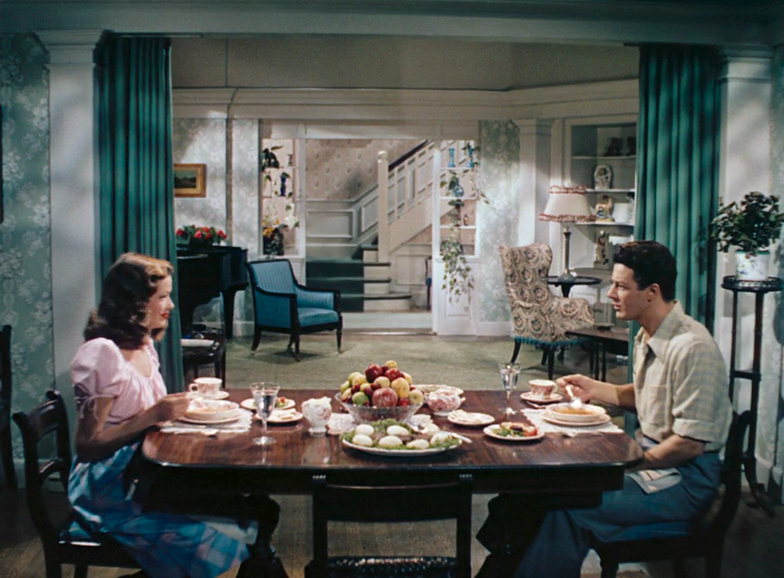

Richard gets out with his life, but only just. They jet off to Warm Springs, Georgia, to get married. After the wedding, Ellen cooks her new husband an elaborate meal to celebrate. It’s Norman Rockwell with a blue filter, the perfect setting for the bride to announce the terrifying news that she intends to never hire any servants. No one but Ellen will ever cook Richard's food, or do his laundry, or touch him.

The notion that a single person could clean any of the grand locations in Leave Her to Heaven is hilarious. But beyond that, Ellen’s determination to cook her own food is presented as an early sign of unhealthy obsession, a worrying rejection of her world of rigorously enforced leisure. This thread follows the happy couple to Back of the Moon, a remote cabin in the woods where they plan to relax with Richard’s younger brother, Danny.

Everything at Back of the Moon is an exaggeration of the stereotypical American hunting lodge. The decor includes a taxidermied deer head and a pair of snowshoes, though it’s hard to imagine Richard actually heading out into the winter to hunt. There’s also a quite substantial display of blue china plates, exactly the sort of thing most people lug up to their remote woodland cottages.

It’s tacky, sure, but it’s a seductive tackiness. You, the audience, are invited to gape at these upper-crust frivolities. Once again, it’s a little like The Picture of Dorian Grey. Ellen is maybe a sociopath, but don’t you secretly want her life? In a prosperous post-war future, you too can rent an Adirondack-style cabin in the woods, decorate it with overpriced crap, cook on an old-fashioned stove, pretend to hunt, and then murder your teenage brother-in-law.

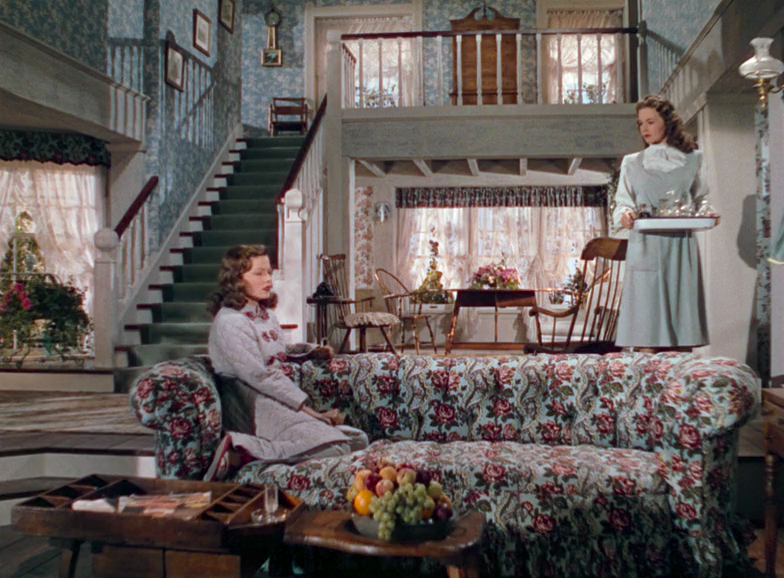

Sadly, the “accidental drowning” of a loved one tends to ruin a mood. Ellen’s family suggests the only reasonable thing: another vacation, this time to the family’s spare home in Bar Harbor. It’s the most ridiculous set in the film, a magic eye of patterned wallpaper, curtains, upholstery, you name it.

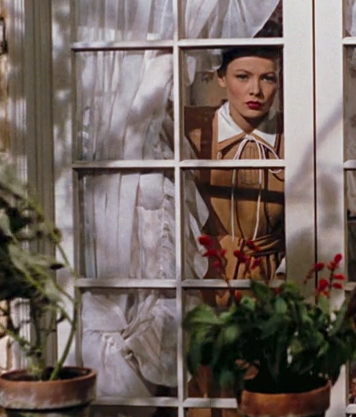

When we first visit, Ellen is even wearing some upholstery - a padded dress that would make a great cover for an armchair. Yet despite this visual affinity to her surroundings, the densely cushioned atmosphere of the house seems to suffocate her. Sharing Richard with her family was bad enough, but the prospect of sharing him with her impending child is even worse. She wanders from room to room, her outfits complementing the walls as if the house is slowly wrapping her in its own malevolent paper - like poor Zawe Ashton in Velvet Buzzsaw.

A short while later, she dresses to match the light, snowy wallpaper and throws herself down the stairs.

Why does she do it? It seems silly to suggest that she throws her life away to spite the wallpaper, but there’s something there. The only time Ellen really seems in her element is all the way back in New Mexico - and not within the shadowy resort, but out in the desert on horseback. Her obsession with Richard - and beneath it her tragic determination to revive her father’s ghost - is powerful enough to tear down the insipid wallpaper of a thousand vacation homes.

In 1945, that may have seemed like the most unholy of manias. After all, white Americans would spend the next 20 years building landscape after landscape of tacky ski lodges, kitschy desert hideaways, beachfront timeshares and Disneyland. But looking back at Ellen from the 21st century, can you really hold it against her? Perhaps she just hoped that her desperate, Freudian marriage would be a nice permanent vacation from all the vacation.