"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

Fossils! They’re cool.

In Ammonite, they’re also a metaphor - a simple one, I’d argue. To be frank, I found the 19th century seaside lesbian paleontology drama to be a bit dull, throwing quite a bit of symbolism up on the screen without ever making a real case that this director needed to make this film about these women.

But I did quite enjoy the sheer number of visual cues, some of which do work quite well. Victorian women, the film suggests, were like fossils. Society confined them to small, dim spaces where they slowly ossified...

Of course, fossils were also the lifelong passion of Mary Anning (Kate Winslet), self-taught paleontologist and protagonist of the film. The film’s central tension seems to be this: 19th century England treated women as museum pieces, but wouldn’t allow their work into the cases of actual museums.

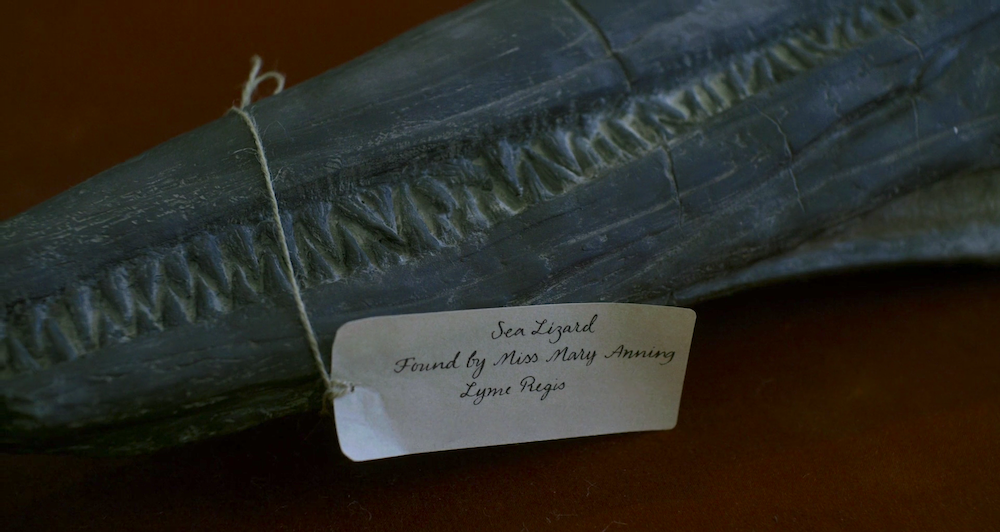

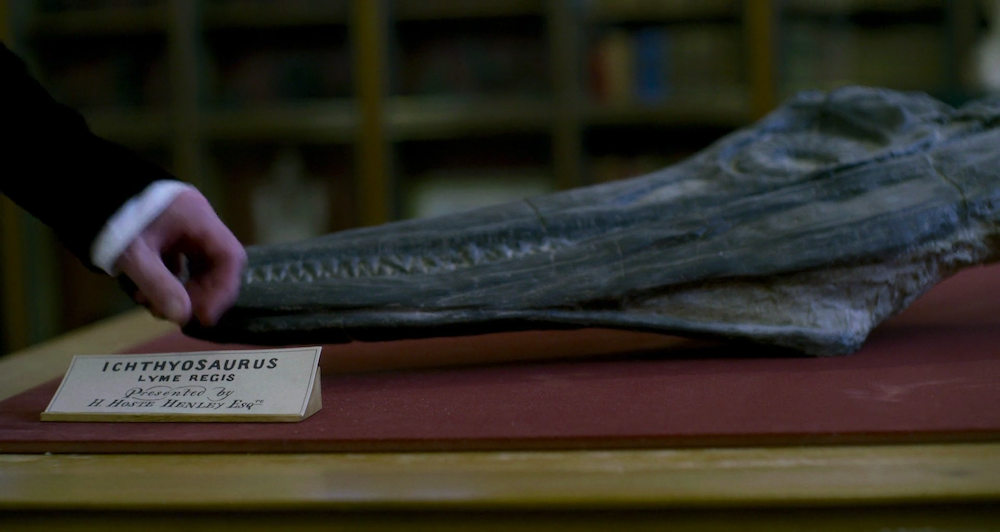

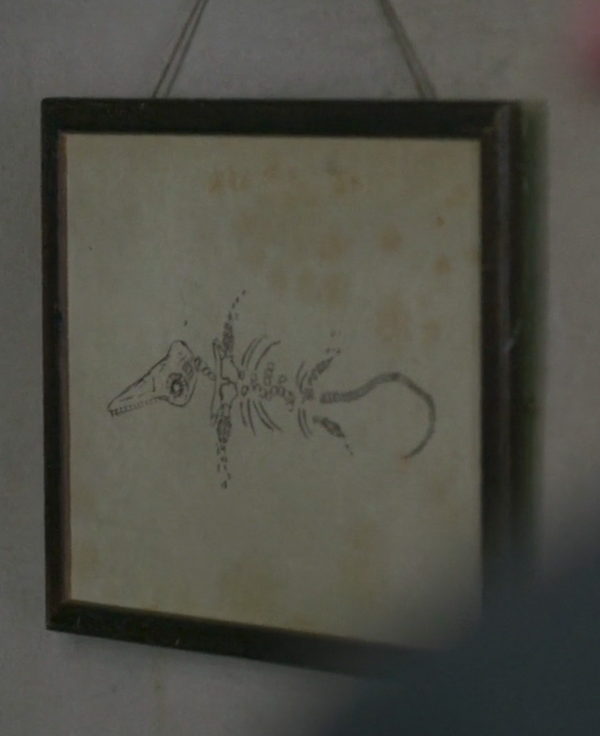

And even if one or two pieces slipped through, they couldn’t be attributed to women. The film opens with one of Mary’s fossils, arriving in the British museum only to be relabeled.

The new one says “icthyosaurus,” which is just “fish lizard” in Greek. Mary’s name is removed, replaced by with the name of the “honorable” gentleman who is “presenting” it to the British public.

Ten Lee cuts to the Lyme Regis, on the Jurassic Coast. Mary Lived and worked within this breathtaking region of England, a 96-mile stretch of coastline that is now recognized as a World Heritage Site for its paleontological significance. The erosion from the English Channel tosses fossils onto the beach every day, and from a remarkable range of the earth’s history: 185 million years, from the Triassic through the Cretaceous.

It is a landscape that lends life to the fossils, or at least a certain echo of life. The pounding waves and the whistling wind are quite different from the enforced silence of the museum case. The marine fossils seem to be leaping back into the water, at long last. It is here where Mary does the actual work of paleontology, finding and studying fossils.

Lee reinforces this by constantly cutting to things that suggest fossils.

There are also plenty of actual fossils, of course. Mary’s shop is a simple space, notable for its lack of Victorian wallpaper. The team of production designer Sarah Finlay, set decorator Sophie Hervieu, and art directors Richard Field, Grant Bailey and Guy Bevitt do an admirable job, subtly representing the social differences between Mary’s world and that of the wealthy Charlotte Merchison (Saoirse Ronan).

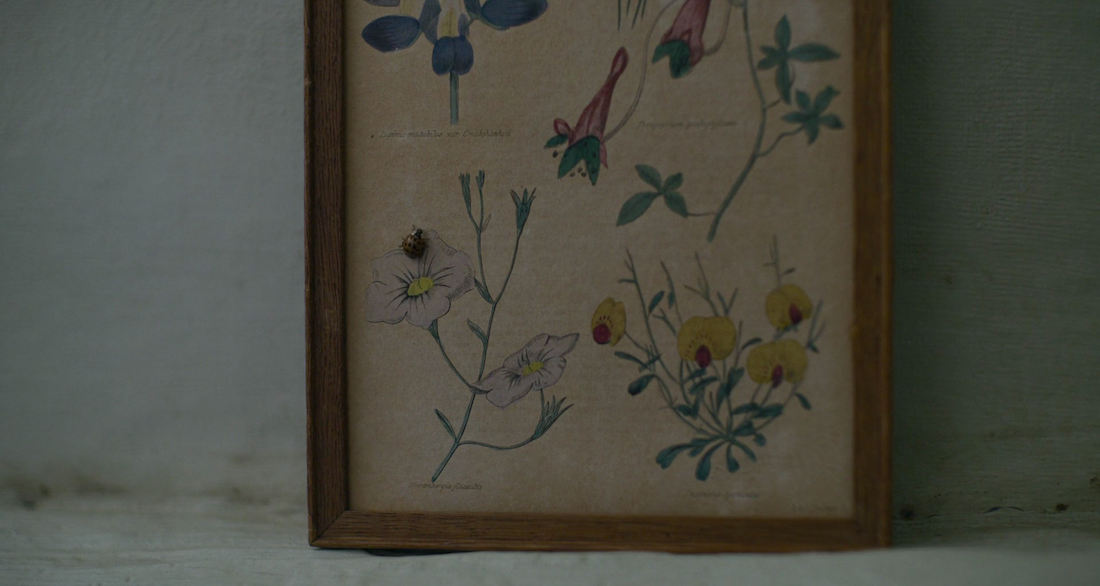

But these subtle visual backgrounds are punctuated by a parade of increasingly obvious close-ups on little objects and creatures that evoke, once more, fossils. Here’s a ladybug, crawling across a framed drawing of flowers that evoke the flattened figure of fossilized plants.

There are close-ups of dead insects, snail shells, tiny figurines, you name it. Flowers are everywhere, illustrated, pressed and still on the stem.

A recital is accompanied by a lovely display of projected cards, including this image of a frozen naval battle, the flames arrested mid-leap. Even the bombast of war can be reduced to a slide, frozen in time and possessed as a trinket. The Victorian penchant for scientific classification and ownership is, after all, another aspect of Empire.

After a barrage of gestures, even the filling of a traditional English pie seems to resemble a fossil, the crust of pastry replacing the crust of rock.

Mary refuses to live like a fossil. The young woman who suddenly bursts into her life, however, is under entirely different circumstances.

My favorite prop in the entire film is the Victorian “bathing machine” with which Charlotte takes her medically-recommended dip in the sea. These were essentially changing rooms on wheels, designed to transport you to the edge of the water so that no one will witness you in your (comically modest) bathing suit until the last possible moment.

It’s evocative and ridiculous, like so many details of the Victorian Era. In many ways, Mary represents an escape for Charlotte from these restrictive spaces and expectations. But can Charlotte achieve that freedom without, in turn, fossilizing Mary?

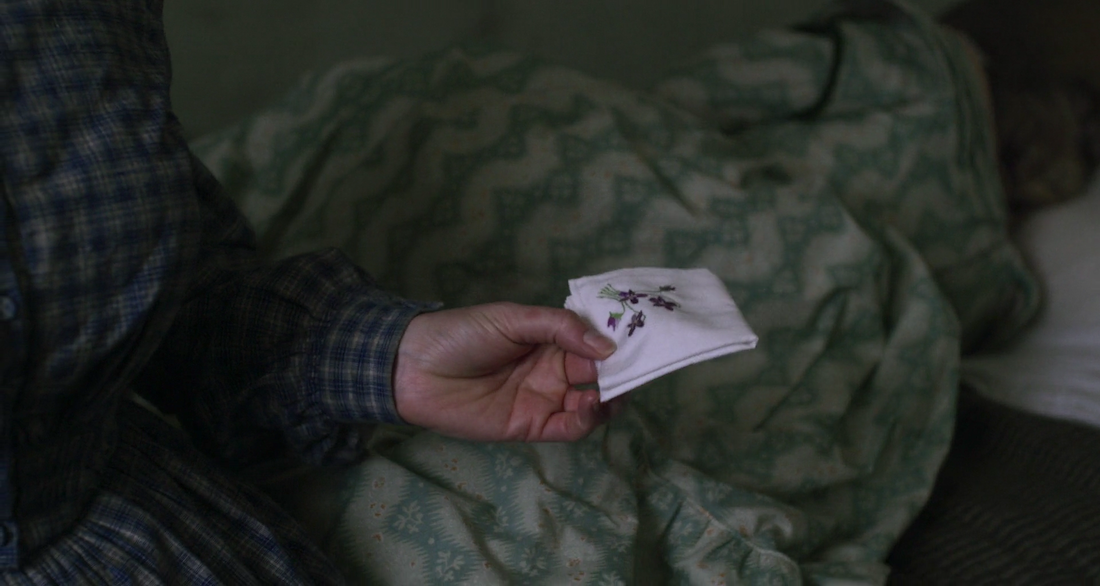

Perhaps the first hint of an answer comes in Charlotte’s departing gift to Mary, a tiny embroidered floral cloth that, in turn, evokes more fossils.

Eventually Mary visits Charlotte’s home in London, where she finds one of her pieces in the ornate glass case. Charlotte’s one act of resistance to her husband is the relabeling of the fossil to recognize Mary’s work. And it’s a nice gesture, but it’s not exactly thrilling.

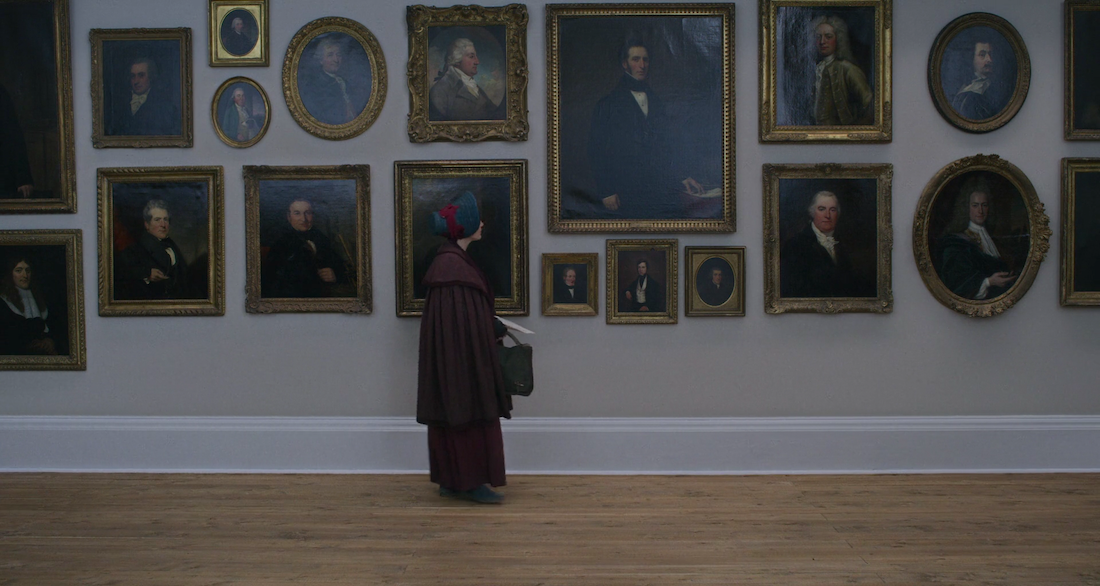

Mary is, in the end, horrified. She turns to the British Museum, where the film ends - though without resolution. Mary’s work certainly belongs in a museum, but what about Mary herself? Despite her determination to not be treated like a fossil, Lee closes with a grand gesture in a hall of portraits, mostly of men no one remembers.

What should we hope for, when it comes to Mary Anning’s legacy? It can’t be this, at least I hope not.