by Chris Feil

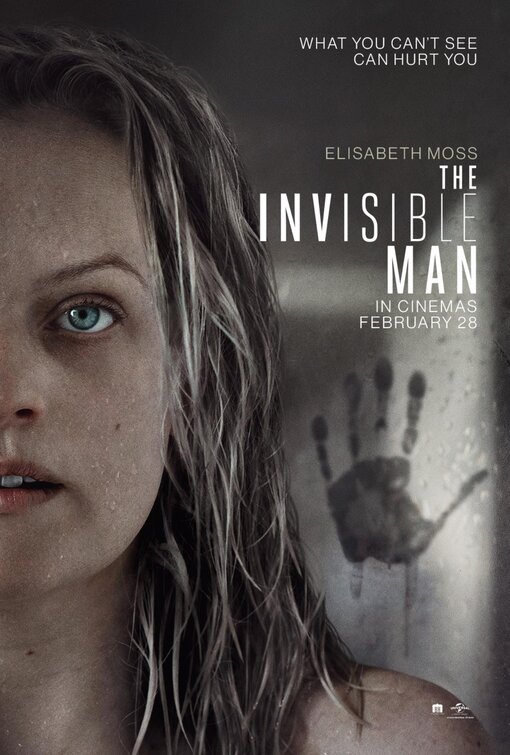

What was once meant for the microwaved territory of the would-be Dark Universe has found new, timely, and sometimes ingenious life as a one-off. Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man morphs its source material with a shift in perspective, making its mad scientist a complete phantom figure to the audience.

What was once meant for the microwaved territory of the would-be Dark Universe has found new, timely, and sometimes ingenious life as a one-off. Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man morphs its source material with a shift in perspective, making its mad scientist a complete phantom figure to the audience.

However, he is a monster all too intimately familiar to the protagonist, Elisabeth Moss’s fraught survivor Cecilia. The film aims to place itself alongside the greats of our current age of horror by placing us thrillingly in her escape from abuse, and in turn offers something fresher to its namesake than previously imagined. If not always a complete success in its genre elements, on a conceptual basis, The Invisible Man is valuable and invigorating as a portrait of the fallout from enduring domestic abuse.

The film opens as Cecilia silently makes her escape from her husband Adrian’s (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) home, the kind of punishingly modern, secure fortress that only Silicon Valley can buy. It’s no mistake that it and its surroundings look like a maximum security prison - Cecilia has endured physical and psychological abuse, isolation from her loved ones, and constant watch from her captor spouse. This opening sequence, near wordless, conveys what she has be victim to and the amount of preparation it’s taken to escape with a tense economy that provides a terrifying foundation for what’s to come. It’s a scenario all too familiar to survivors of domestic abuse, and Whannell aims to make something as entertaining as it is thoughtful in engaging with their truths.

Much of the film chases the emotional depth and precision of this opening stretch with varying success. Cecilia spends the coming weeks hiding out with her police officer friend James (Aldis Hodge) and his college-bound daughter Sydney (Storm Reid). As she begins to reclaim small steps of normalcy, news comes that Adrian has taken his life, leaving his fortune to Cecilia. But Cecilia remains uneasy as the aftermath of trauma continues to take a toll, exacerbated by the growing sense that she is being haunted by Adrian’s unseen presence.

The result is a film that is less like Hollow Man (though there are some similar and less convincing visual effects at play) and more akin to Sleeping With the Enemy with the paranoia and trauma cranked to 100 as it focuses on the long-lived affects of gaslighting and abuse. Here is where the film brilliantly uses horror tropes and spins them on their head. There’s as much horror to what Adrian inflicts on Cecilia as there is in her network refusing to believe her.

One just wishes the film didn’t also succumb to predictability and occasional visual chintziness. Its routes to explaining the science behind Adrian’s invisibility distract and diffuse what’s naturally scary about the concept, while Adrian’s will-executor brother Tom (Michael Dorman) makes for a secondary villain too mustache-twirling for the real-world horror the film is going for. And when the film gets bloodthirsty, it feels like a divergence from the film’s themes rather than a natural extension of them. Perhaps its that the film’s rather silly missteps stand in such contrast to its successes, but at least The Invisible Man does always recenter on its narrative target after stretches that work significantly less.

Much of the film’s power is also indebted to the performance from Moss. By now, she’s become a natural choice for such freakout material at this, and that’s part of the key ingredient that makes the film work overall. Aside from the tension mined from her very physical and soulful specificity with which she performs Cecilia’s responses, she enacts something intensely intellectual to the film. Moss is almost too natural at playing “crazy”, perhaps daring the audience to imagine that the invisible Adrian is all in her head or a manifestation of processing her trauma. It’s daring that the film and Moss’s performance challenges the audience to see how they might perpetuate the cycle in this way. Do we have an American actress making the case for “performer as auteur” as the likes of Isabelle Huppert have done? Moss might be staking a claim for herself, even in something as mainstream as this.

With a steady stream of set pieces, The Invisible Man sometimes stumbles to match the effectiveness of its perspective with its individual parts. However, instead of a piece of cynical branding and despite its clunky patches, Whannell and Moss deliver a valuable piece of horror storytelling that rewards with a cathartic force.

Grade: B-