by Chris Feil

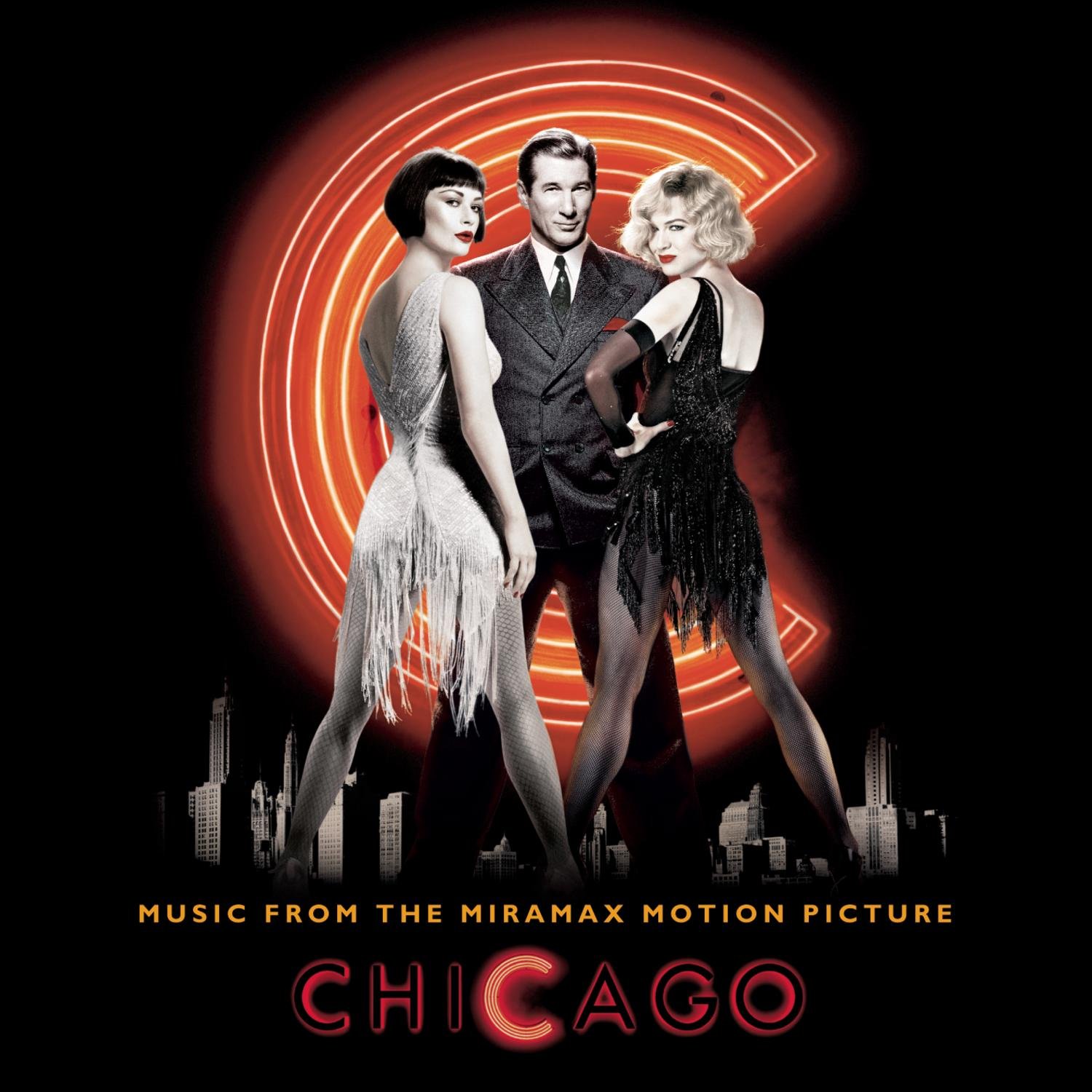

With Renée Zellweger likely taking home another Oscar for her performance of Judy Garland this Sunday, it feels like a full circle moment for the actress’s career and Oscar’s relationship with musicals in the modern era. Rob Marshall’s take on the Kander and Ebb masterpiece Chicago was a platonic ideal between Academy voters (and the public) who sneered at the genre and its fans that were reinvigorated by the audacity of Moulin Rouge! just a year prior. Chicago injected new life into a previously dead genre, reigniting Oscar’s love as well, from all-out musicals to especially musical biopics like Zellweger’s Judy.

With Renée Zellweger likely taking home another Oscar for her performance of Judy Garland this Sunday, it feels like a full circle moment for the actress’s career and Oscar’s relationship with musicals in the modern era. Rob Marshall’s take on the Kander and Ebb masterpiece Chicago was a platonic ideal between Academy voters (and the public) who sneered at the genre and its fans that were reinvigorated by the audacity of Moulin Rouge! just a year prior. Chicago injected new life into a previously dead genre, reigniting Oscar’s love as well, from all-out musicals to especially musical biopics like Zellweger’s Judy.

After many decades on stalled attempts to adapt Chicago from stage to screen, Marshall’s solution is to capture most of the numbers as imagined fantasies in the mind of Zellweger’s murderous Roxie Hart. Chicago was Bob Fosse’s on the stage, and this take borrows seamlessly from what Fosse was already doing (and in turn, stealing from Fellini) onscreen in films like All That Jazz. And he makes it all conceptually clear to the audience within a flash of the film’s perfect opening number that shares title with that Fosse film.

It felt revolutionary at the time, a smart way to explain the use for songs to an audience demanding justification for this purely cinematic expression. But this trick would become an easy out for some lesser musicals to come - a shame in becoming a “break out into song” musical resulted in some normalized creative backflips to pacify the genre to lingering doubters. Even if it feels emblematic of how the genre would needlessly justify its impulses, you have to admit Marshall’s idea helps integrate the score’s vaudevillian separateness from the plot with numbers like “Cell Block Tango”.

For Chicago however, this doesn’t always function as genre cowardice and can serve to enhance the sliminess of its ensemble of manipulators. Take Richard Gere’s Billy Flynn, turning the press and the court room with his theatrical spin and wielding his charm like a weapon. In “We Both Reached for the Gun”, Marshall turns his behavior into literal theatre, with Flynn the puppet master orchestrator of an entire narrative shift in Roxie’s favor. It’s a very literal interpretation of the number but also an ingenious one that meets the material’s influences with Marshall’s own conceptual imagination.

Turning the songs into an imagined playground also allows some truth to take root in regards to Roxie’s character. Like Sally Bowles, Roxie Hart’s situation makes so much more sense if she’s not a flawless singer and dancer. While Zellweger’s vocal restraints have been overblown by some of her detractors (and those complaints amplify the goodwill in seeing her sing again onscreen this year), there is something about her vocal limitations that makes her daydreams all the more pronounced in their delusion. But even more importantly, it serves the musical’s thesis about the gaucheness of celebrity without talent. After she’s a murdering headline sensation, Roxie’s voice is insignificant compared to her persona.

And with Zellweger again using her vocal limits to reflect the failing Judy Garland, it perhaps shows a willingness to be vulnerable and unpolished that also smartly serves her heroines. Something we could have appreciated more at the time.

All Soundtracking installments can be found here!