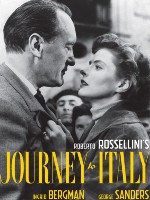

Cinema is the ephemeral crystalized. The camera transforms the now into a remembrance like the petrified bodies of Pompeii, those monuments of frozen life that frightened Ingrid Bergman in Rossellini's Journey to Italy. I still recall when I first watched that classic and felt as if I was witnessing a film reacting to its own limited existence. When Bergman cries we see a star realizing she's no more than a shadow of yester, like those burnt cadavers her image is an unwitting memento mori. Since then, cinema's relationship to time has fascinated me, especially when it comes to the portrayal of memory. Rossellini showed me cinema remembering itself and Resnais shattered the recollection of personal history, Chris Marker paralyzed the days long gone and Varda made them abstract.

Cinema is the ephemeral crystalized. The camera transforms the now into a remembrance like the petrified bodies of Pompeii, those monuments of frozen life that frightened Ingrid Bergman in Rossellini's Journey to Italy. I still recall when I first watched that classic and felt as if I was witnessing a film reacting to its own limited existence. When Bergman cries we see a star realizing she's no more than a shadow of yester, like those burnt cadavers her image is an unwitting memento mori. Since then, cinema's relationship to time has fascinated me, especially when it comes to the portrayal of memory. Rossellini showed me cinema remembering itself and Resnais shattered the recollection of personal history, Chris Marker paralyzed the days long gone and Varda made them abstract.

While these are names of the European vanguards, cinema as theatre of memory isn't a phenomenon exclusive to the art house. We need only look at this year's Oscar contenders to find ways of picturing memory on the big screen…

Two of 2019's Best Picture nominee make ostensive use of memory dramatized. Greta Gerwig reimagines Louisa May Alcott's Little Women by scrambling its chronology. No longer do we perceive this story as a chronicle of childhood giving way to adulthood. Now, it's a tale of remembering the summer of youth in the winter of grown-up life, a dynamic which is made clear by the use of diverging color palettes. Golden ambers for teenage warmth and greyish blues for present hardships. This change fully transforms the story's emotional impact, allowing the time periods to dialogue with each other, a discussion that's often characterized by the pain of loss or nostalgic longing. Two different mornings shot exactly the same way, one ending in happiness the other in mourning, are thus joined in matrimony with heartbreaking editing.

The Irishman uses the mechanism of remembrance to give new context to a series of themes we've seen before in Scorsese's filmography. When looked through the prism of an old man's memory, moments of violence are joyless affairs, the final consequences of bloodshed evident everywhere we look. As the film progresses, the emptiness that flowers out of a violent life is too great to ignore. This sorrowful requiem isn't without humor, though, and Scorsese fuses the exercise of filmed memory with black comedy by introducing each new character with a written description of their death. For someone whose old buddies are all six feet under, remembering old faces must feel like a trip through a crypt. Recalling a wasted life is the same as meditating on Death.

Little Women and The Irishman do their sojourns through memory lane by way of subtle color grading and incisive editing. Not all theatres of memory are the same nor are their mechanisms similar. The painful glimpses into a dead matriarch last moments take the A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood into an idiom of abstracted theatrical space. There's no reenactment of past scenes, but a meeting between a boy made man and his mother, both lost in the theatre of his recollections. Regarding Almodóvar's Pain and Glory, memory and cinema are even more interwoven. In that doubly nominated Spanish film, a director's childhood becomes material for new celluloid dreams and romances long lost are resurrected for a kiss in a quiet night at home.

The Two Popes starts its biographical flashbacks by suggesting memory as architecture and mural painting while I Lost My Body fragments recollections by making them all about touch. Still in the realm of animation, the short Mémorable mixes painting and fractured psyches to suggest an artist losing his sense of self to dementia. When his memory of his wife fades, she turns into nonfigurative paint strokes and only the material record of past portraits can show a life lived and now forgotten. Sister, a short by Siqi Song, uses the plasticity of fuzzy felt to materialize false memories. Their falsehood is only revealed at the end, making their previous plushy appearance a cutting contrast to the painful reality of artifice.

Many of the nominated documentaries infiltrate their creators and subjects' memories, registering moments in life that are now lost to time and to film history. A beekeeper's mother will forever live while Honeyland is around to be watched and a country's history will not be a forgotten memory for as long as films like The Edge of Democracy speak their truth in shouted abandon. For Sama is the remembrance of a mother to her child, while In the Absence uses digital ghosts to recall one of South Korea's darkest chapters. The Cave is a cinematic memory deliberately constructed for a world that shall never misremember their complacency while such horrors took place.

There are other examples to mention, like The Lighthouse's ambivalent monologues about past crimes, Judy's traumatized flashbacks, and Rocketman's musicalized therapy session. It's possible to rhapsodize endlessly about this topic, but I shall stop if only for the sake of brevity and the reader's patience. To finish, let’s ask a simple question. Which of these instances of cinema as the theatre of memory moved you the most?