As a sequel to our recent look-back at the 42nd Oscars , please welcome guest contributor Orrin Konheim...

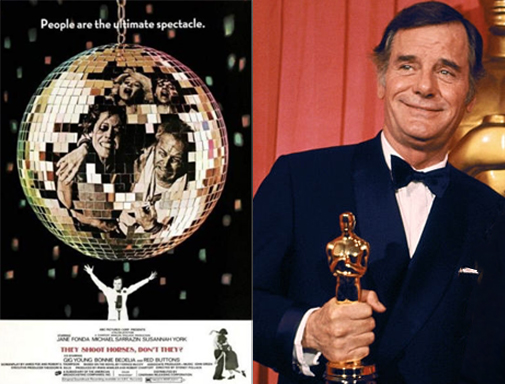

Fifty years ago, the Academy Awards marked an odd milestone when they awarded a Best Supporting Actor Oscar to Gig Young for They Shoot Horses Don’t They (1969) although they didn’t know history was being made at the time. Eight years later, Gig Young would shoot his wife of three weeks (and then himself) in the only known instance of an Oscar-winning actor committing murder.

His tale is a disturbing one with few answers...

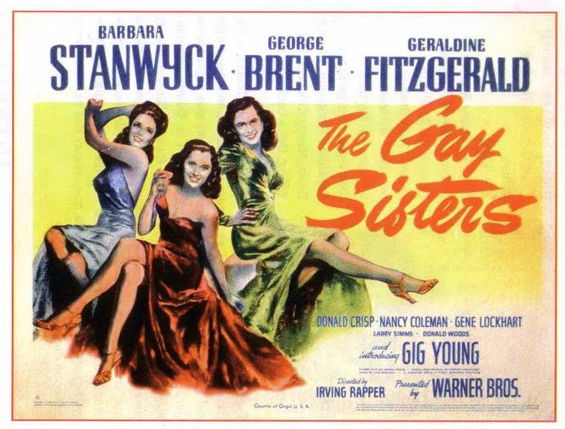

Gig Young was a steady character actor for three decades with an honorable war record in the Coast Guard to boot. Born Byron Barr, he came to Hollywood from Washington D.C. shortly after high school on the condition that he pay half his friend’s gas budget and worked as a used car salesman until he got a scholarship to the prestigious Pasadena Playhouse. From there, he got a contract with Warner Brothers and in a film called The Gay Sisters (1942) he played a character named "Gig Young" whose name he immediately adopted. Though it was his fourth credited role his billing was "and introducing Gig Young" as you can see on the poster.

In addition to his steady career, Young was a charming presence to the public as a favorite guest of Johnny Carson as well as a host of a pseudo-talk show launched by Warner Brother’s Studios’ new television division.

Actor Al Lewis summarized Gig Young’s career of his friend: "He was always the best friend of the guy who gets the girl, he was never the guy.” He starred in four films with Doris Day and he would be passed over for Cary Grant.

All this occurred while Young was having severe mental issues. While he was known for his congeniality on sets, those who knew him better could tell he had his own sense of paranoia. “Gig was a wasted human being…he was like a manic-depressive and paranoid,” a source told the National Enquirer after his death. His first marriage eroded while he was overseas during the War and his second was a natural death from cancer, but his third (Elizabeth Montgomery of “Bewitched" fame, 1956-1963) and fourth wives (realtor Elaine Young 1963- 1966) reported mental and physical abuse. Montgomery described him as having an internal loneliness in his obituary and former lover Harriette Vine Douglas said “he did everything to keep his mind off his own emptiness” later adding “He could win an Oscar and walk away two weeks later feeling like he was a total failure.”

He also exhibited a strange paranoia after his divorce to Elaine Young and attempted to disown his daughter, Jennifer, by launching a five-year lawsuit absolving himself of paternity (he lost). Young felt that denying his daughter was a reaction to the disappointment of divorce and hoped he might eventually come to accept her again.

Gig Young's Oscar nominated roles: Come Fill the Cup (1951), Teacher's Pet (1958), and They Shoot Horse Don't They (1969)

Gig Young's Oscar nominated roles: Come Fill the Cup (1951), Teacher's Pet (1958), and They Shoot Horse Don't They (1969)

Things were more compounded with his mental state when he went to “Therapist to the Stars” Eugene Landy for treatment in the mid-1960s. Landy is best known for sabotaging the recovery of Beach Boy Brian Wilson (dramatized recently in the film Love and Mercy) and had his license revoked by the state of California in 1991. Gig Young developed a valium addiction that might have had something to do with a therapist not administering it correctly.

They Shoot Horses Don’t They was by all accounts a career highlight for Gig Young though he’d been nominated twice before. Based on a 1935 novel about the depression-era trend of dance marathons, They Shoot Horses Don’t They portrayed the trend for the nightmare fuel that it was: unimaginably desperate people breaking down physically and emotionally for the slimmest chance at a few hundred dollars. The protagonist’s role of the suicidal Gloria allowed Jane Fonda to show she could be more than a pin-up girl (see Barbarella), the film also displayed Young in a new light. As the event’s promoter and announcer, Rocky who reveled in the cruelty of the spectacle without a hint of irony. Like Young’s inner life, Rocky encapsulated the joint persona of a man who performed well on stage but who had a weariness about the grimness of his reality in poignant images that found him positioned in front of a mirror staring at himself.

When Lewis was on the set of They Shoot Horses Don’t They he told Gig that he had a shot to win an Oscar because “no one had seen Gig Young sweat before.”

Over the next eight years, Young’s alcohol, drug use, and other undisclosed ailments became visible and he became far less in demand by producers. On the first day of shooting for Blazing Saddles he was carried off in an ambulance from convulsions. Gene Wilder would later make his part of “the Waco kid” famous. While the common story is that he was drunk, his recorded diaries indicated he was having an epileptic episode (another clue as to his complex mental state).

Peers said the pressures of trying to break out of limiting supporting roles mounted on him but Young remained as congenial right before his demise as he was during his prime. In a newspaper interview just six weeks before his death (eerily entitled “Survivors”) and a televised interview a few months prior (embedded above), one can see a man doing great work in the theater, optimistic about his future, and ready to put the past behind him.

In an interview with the National Enquirer shortly after his death, Paul Steiner, an author and close friend of Young revealed that the actor had skin cancer (something Young hadn’t disclosed): “When big parts, great parts… didn’t roll in (after his Oscar win)… he started a sad descent toward disaster. He had skin cancer… he was afraid of growing old.”

On an October afternoon around 2:30 p.m. in a New York City apartment, Gig Young shot a bullet through the back of the head of his new (and fifth) wife, Kim Schmidt, followed by one into his head. Schmidt was just 31 years old and Young was 64. To further compound the lack of context, Young had a peculiar habit of tape recording his therapy sessions and kept a meticulous diary as well. That diary, though, was unfilled during that doomed marriage (the last three weeks of his life). Police didn’t have much to go on either but they did surmise that it wasn’t a pre-meditated murder.

Gig Young was buried by his sister in North Carolina and the grave bears his birth name but doesn’t mention his illustrious career. Simply his birth and death. The star left behind $200,000 and an Oscar that was lying right next to him when he died. He called winning the Oscar “the greatest moment of my life” and it meant a lot to a couple other people who fought a court case over the physical possession of the statue in 1997 between his manager Marty Baum and Jennifer Young . Perhaps due to his loneliness, Young developed a strong attachment to Baum for never giving up on him (he takes up the bulk of Young’s Oscar acceptance speech) and bequeathed him the statue. Baum used the statue as a window ornament at his office but the two eventually agreed that she would get it upon his death. In 2009 when Baum passed away, Gig's once disowned daughter finally inherited the statue.

Orrin Konheim is a regional journalist in DC and Richmond, a contributor to a smattering of film publications, a fan of The Film Experience for over a dozen years and blogger at sophomorecritic. You can follow him on twitter. He is taking donations at this difficult time for his film research and writing through his new patreon account.