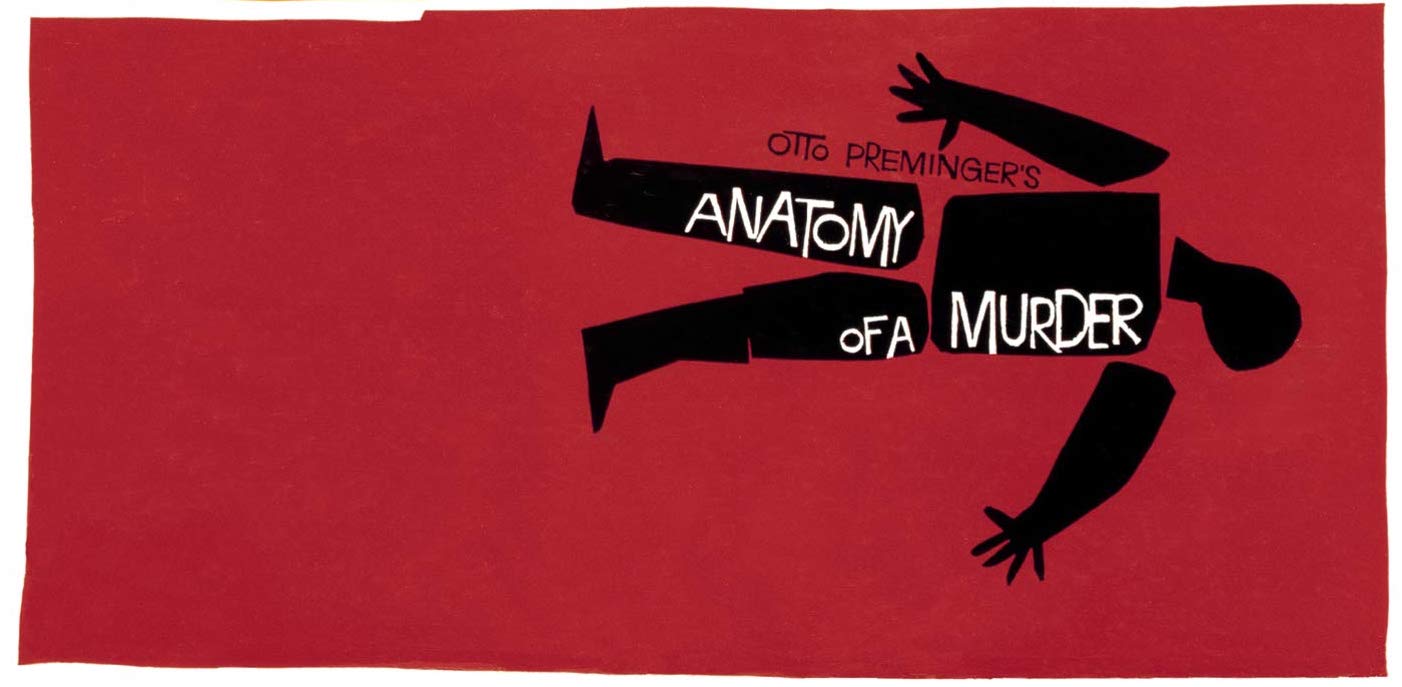

In this series members of Team Experience share their feelings for movies they have watched multiple times and that they can never get enough of. Here's Michael Cusumano

I can’t remember what originally drew me to Anatomy of a Murder. I certainly never held strong feelings toward the courtroom genre in general or the films of Otto Preminger in particular. I do recall a youthful obsession with George C. Scott that might explain it; Dr. Strangelove and The Hustler both would both qualify as top contenders for this series.

Whatever path I took to Anatomy of a Murder, once discovered it was never far from my rotation. You would think courtroom movies would be ill-suited for repeat viewings since most are structured like mysteries where the truth is gradually forced out into the open. Once the secrets are spilled, what is left for the return visit? But therein lies the appeal of this surprisingly idiosyncratic title...

Anatomy of a Murder isn’t especially concerned with the sort of courtroom bombshells that leave the judge banging his gavel for “Order!” over the din of gasping spectators. The truth is obvious from day one and even the last-minute surprise witness is brought in to confirm what we already knew. This frees up the trial to be an elaborate dick-waving contest between the attorneys, an approach that is endlessly entertaining and feels a lot closer to the reality.

Put simply, Anatomy of a Murder is my favorite courtroom drama ever because both sides of the trial are utterly full of shit.

The defense knows their guy is 1000% guilty, having walked into a bar and shot an unarmed man five times. The victim had it coming, sure, but they can’t explicitly stake their defense on that. Instead they attempt to eke an acquittal out of an arcane legal loophole called “irresistible impulse” which amounts to something less than “legally insane” and a smidge more than “not guilty because I really, really wanted to shoot the guy”. The film even undercuts the supposed vigilante righteousness of the killing. The defendant executed the man who raped his wife, but the film is careful to note that it was less about justice and more about a violent brute asserting ownership over his property.

Even good ol’ Jimmy Stewart as the cagey proto-Matlock defense attorney doesn’t care about truth, and justice, so much as he’s sore over losing an election to the current district attorney (a dunce) and would enjoy nothing more than to give him a public legal pantsing. He seems reasonably satisfied that right is on his side, but it’s hardly a priority. Battered nobility is the default mode for most defense attorney protagonists. Stewart’s default is bemusement.

On the opposite side, the prosecution is led by a predatory George C. Scott. We sense that they probably realize the murdered man is a rapist who got what was coming to him, but they know better than to build a case around asking a jury to put aside emotion. So they put the rape victim on trial for being a tramp who was asking for it, cynically believing the jury will be a lot more receptive toward that line of attack. It should be noted that the film never shares this view, framing attacks on her character as a shameless smear from the prosecution and toxic jealousy from the husband; For a sixty-year-old film about salacious material it holds up shockingly well to modern sensibilities.

What really seals Anatomy’s rewatchability is that, in the end, the truth somehow manages to fight its way into the trial and a shaky version of justice actually does win the day. It’s one thing when a courtroom movie aims to inspire. It feels nice, but we’re instinctively skeptical. The film is selling something. But when a film this cynical says the system works, well, there’s something comforting in that.

Previously in Over & Overs...

- Moonstruck (1987) by Deborah

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) by Lynn

- My Girl (1991) by Camilla

- Sister Act (1992) by Kyndall

- The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) by Mark

- Sense & Sensibility (1995) by Claudio

- To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything Julie Newmar (1995) by Chris

- Sugar & Spice (2001) by Spencer

- Marie Antoinette (2006) by Claudio

- Julie & Julia (2009) by Ginny

- Moonrise Kingdom (2012) by Ginny