by Nick Taylor

Ah, 1947. Back when the Golden Globes only announced their winners and neither NYFCC (age 12) nor NBR (age 2) had supporting acting categories. Searching for alternatives to Oscar’s lineup -- as we like to do when approaching a new Smackdown -- is appealingly open-ended. There are ways to find other options without awards bodies, though. The simplest is to call upon decades of film history to see which of any year’s most durable films have noteworthy female performances. For instance, has any other 1947 film so formidably established itself in the canon as Powell & Pressburger’s Black Narcissus... particularly as an offering of great actressing?

Centered on a group of Anglican nuns instructed to open a school on a Himalayan mountainside already infamous for scaring off other settlers, the film maintains the directors’ penchant for overripe atmosphere and jaw-dropping spectacle...

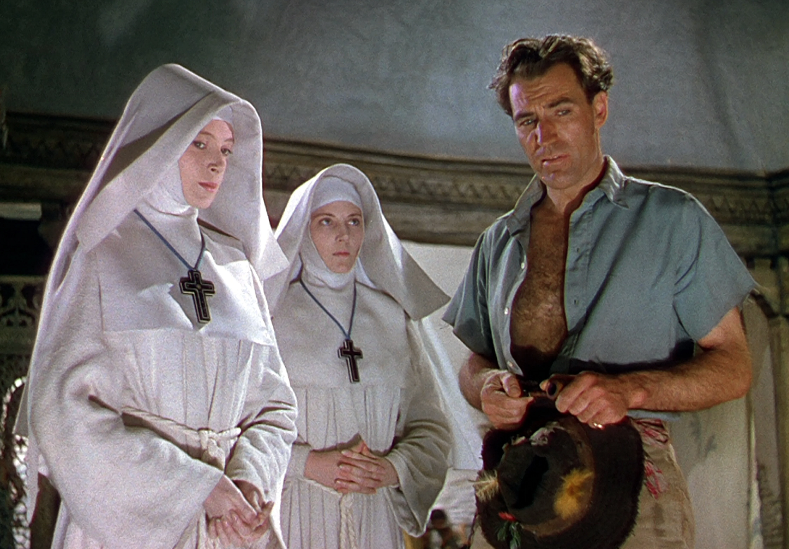

Black Narcissus boasts an indelibly multifaceted lead performance from Deborah Kerr as Sister Clodagh, the newly annointed leader of these nuns, but for the subject of this week’s article, we’ll be discussing Kathleen Byron’s obsidian supporting turn as Sister Ruth. This nun does not take well to this new setting but is very excited by the presence of a swarthy Englishman.

The very first thing we hear about Byron’s Sister Ruth is that she’s . . . . unwell, in a way neither Sister Clodagh nor her Reverend Mother feel quite comfortable describing in detail. They both seem concerned for Sister Ruth’s well-being but also a little frightened of whatever illness they’re implying, as though speaking it aloud might summon her. Sister Clodagh thinks Sister Ruth coming to this convent is a bad idea, likely to exacerbate her ill health, though the Reverend Mother believes the fresh mountain air may reinvigorate her. Even when we finally see Sister Ruth, her face as white as her robes and staring into the abyss as she rings the convent’s ornate, cliffside bell to signal the start of the day, her wrongness is hard to categorize but instantly present, especially once she starts grinning at an eerie horn blast that accompanies her ringing. Is she physically ill, or at least prone to illness? Is she psychologically disturbed? Is she just a bad person having a terrible time?

As it turns out, the answer given by Byron, Powell & Pressburger, and the film’s other artists is a resounding “all of the above”, portraying Sister Ruth as an already unstable figure pushed to the brink by this Himalayan outpost. By making her so unwell from the out and framing her fall as so self-mediated, her arc is shorn of any tragic or overtly sympathetic edges in favor of a doomed sense of inevitability. Sister Ruth’s status as an embodiment of repressed neuroses gone haywire couldn’t be more apparent. The fact that she bears a resemblance to Sister Clodagh automatically lends Sister Ruth more thematic weight as an extreme foil to her, yet Byron and her directors elevate Sister Ruth beyond a mere device. As maligned as she is, she’s never a reducible idea or a source of one-note villainy. It’s clear that among the non-Clodagh nuns, the character of Sister Ruth and Byron’s performance are given the most shaping by Powell & Pressburger, and Byron amply rewards their attention. Her expressions, movements, and postures are perfectly suited to her directors’ exaggerated style without resorting to caricature or overwhelming scenes that aren’t about her. She’s always a legible presence, modulating her gestures precisely no matter where she is in Cardiff’s compositions.

But Sister Ruth is as susceptible to physical maladies as she is psychological ones, and the film’s uncredited makeup team (listed here) takes great care with her appearance, giving her clammy, pale skin, chapped lips, and bloodshot eyes. Like Byron herself, these effects are able to register at all times, albeit in a less Gothic key. Byron dramatizes these illnesses in her bodily actions, sometimes rushing unsteadily from place to place or seeming visibly exhausted. In close-up she occasionally looks as though she’s trying to force her eyelids open to keep from fainting. Sister Ruth frequently looks as though she’s barely holding herself together, making the straight-backed vigor with which she rings the convent’s bell even more startling. There’s a great sense of purpose to her when she’s staring into the abyss or watching an object of her fascinations, one that never feels contradictory to her sickness or level os fatigue.

Part of what makes Sister Ruth’s madness so potent is the sheer size of it. Though all the nuns are bothered by this village and its people, Byron scales her own reactions slightly beyond these contexts. She certainly arrives with her own racist hang-ups and bad faith views of the locals, sourly trying to shoot down Sister Honey’s initial plans to teach the children English because they’re too stupid to understand her. It’s almost funny to see how much she doesn’t care about the children she’s been assigned to instruct, often not even pretending to teach them as she gazes out the window at Mr Dean or remaining lost in thought. But compared to the other Sisters, her breakdown feels more rooted in her growing dissatisfaction with the faith and her newly felt horniness than becoming unmoored by this specific environment. When Sister Ruth bursts into Sister Clodagh’s office to report the status of a new patient who nearly died from her injuries, she’s breathless but also a bit excited recounting the details of the ordeal while covered in the woman’s blood. It almost doesn’t matter who this person is or what part of the world they’re in, except that she has felt this stranger’s pain and is now energized by it. When she starts biting back against Sister Clodagh, the purity of her malice is frightening in its intensity and directness.

This is all the more impactful because Byron binds Sister Ruth’s obsessions into one concentrated force. Her erotic fixation on Mr Dean (which she plays as a girlish nervousness in their few interactions), her displacement in the convent, her jealous rivalry with Sister Clodagh: Byron shades all of these developments expertly while weaving them together as symptoms of the same mania. These threads culminate in a late-night confrontation with Sister Clodagh after she finds out out Sister Ruth intends to leave the order. Ruth opts to celebrate this with a massive transformation, one involving a whole new sense of style with colors that set her at violent odds with the desaturated, chalky white of the nunnery.

Her actions in the final third of Black Narcissus reach new extremes, seizing the opportunity to fulfill her deepest desires rather than just watching them, yet Byron’s performance remains fully controlled. She plays Ruth’s defiance of Sister Clodagh and her ardor for Mr Dean with a new level of intensity, kaleidoscopically shifting through these high-scaled emotions without sacrificing nuance or luxuriating in the camera’s already considerable attention. There’s nothing indulgent in Byron’s work, which feels as defined by its own might as it does a palpable sense of collaboration between her and her directors. Even as Ruth begins deteriorating in her final sequence, Byron maintains a technical skill and emotional directness that’s perfectly balanced to Powell & Pressburger’s narrative and aesthetic demands. You couldn’t get a Sister Ruth this affecting if Black Narcissus didn’t have the humid, overwhelming style of its direction, nor an actress so willing to meet those demands and enrich them with her own sense of danger and provocation. For all the folks who rightly deserve credit for the success of this character’s arc, there simply isn’t a Black Narcissus without Kathleen Byron.