Michael Cusumano here to celebrate a film that is so much more than just another "based on a true story" prestige pic. I have noticed that Bennett Miller’s Capote is often shoved into the biopic genre in a way that diminishes the film’s achievements.

Lesser biopics bask in the glow of reflected importance coming off their subjects. Significance through osmosis. They value the flush of recognition over insight, and the accumulation of incident over meaning. Capote on the other hand is crafted with a stark, unwavering discipline. It has more in common with a portrait of artistic self-destruction like Black Swan than with Walk Hard inspirations like Ray...

The Scene: Movie Premiere

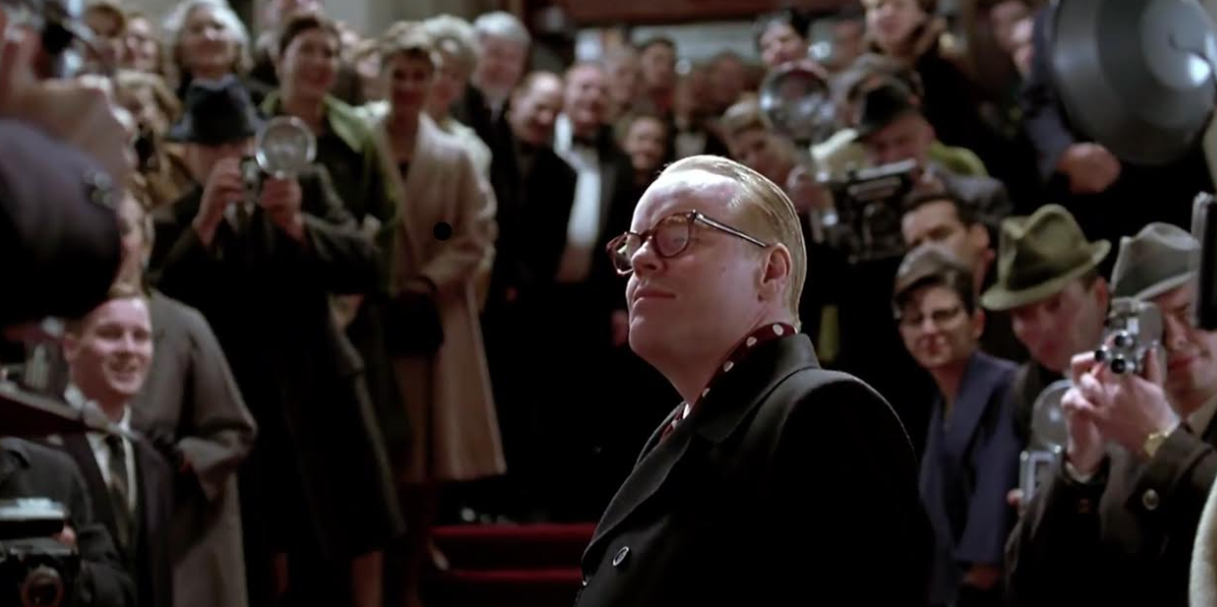

Take my favorite scene: A brief, late-in-the-film sojourn to the 1962 premiere of To Kill a Mockingbird. Right away, Capote resists the urge to fill the scene with a parade of celebrity reenactments. It must’ve been so tempting to cast someone as Gregory Peck so we can hear that deep, familiar voice. But then that would be a distraction from the point of the scene, which is the contrast between Nelle Harper Lee and Truman.

The scene is the payoff of a subplot about the publishing of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Earlier when another writer asks about her children’s book about birds, we might worry Capote is headed for cheap historical irony territory, a Titanic “something Picasso” moment. It becomes clear, however, that Mockingbird is not mentioned for the cheap jolt of recognition, but as a counterpoint to Truman’s obsession with fame. Harper Lee flees from praise while Truman holds court with his admirers. As a result Nelle sees clearly while Truman is perpetually lost in a fog of his own ambition (and gin).

Everyone rightfully talks about Hoffman’s brilliance, but it should be equally noted how the direction and writer set the stage for his success. There is a reason this is one of the projects that allowed Hoffman to display the full extent of his talent, and it wasn’t just that he made a surprisingly convincing Capote, despite being no one’s first casting. Dan Futterman’s script is a marvel of economy. One of my favorite examples is early in the film when, after spending his first day in Kansas sticking out like a sore thumb, he greets Nelle in the hotel lobby dressed in an ordinary black suit and does a little “Happy now?” twirl. Without a word of dialogue we know everything about their relationship, the tension between her practicality and his flamboyance. The fact that the actors don’t have to wade through pages of lugubrious exposition frees them up to simply, fully embody these characters. On repeat viewings I find myself marveling at Keener’s performance as much as Hoffman’s. It’s a stunningly confident piece of acting. Like the film around her, she adds nothing for effect.

By the time the film reaches the premiere we know their dynamic so well we can read their slightest gesture or inflection. Nelle finds Capote bathed in green light at the bar, as if literally immersed in a gimlet. She patiently wades through his self-pitying monologue about trying to finish the book, simultaneously making not just her big night about himself, but also the impending execution of two men. He then fails to summon a single word of praise, managing only to mutter a bitchy “I frankly don’t see what all the fuss is about” (a Hoffman line-reading for the ages).

I frankly don’t see what all the fuss is about”

(a Hoffman line-reading for the ages).

The fact that he’s not merely being snidely dismissive, but snidely dismissive after seeing the world premiere of To Kill a Mockingbird is an example of using the audience’s historical perspective well.

Truman Capote’s life following the events of the movie is not a happy story, and without being heavy-handed, this brief conversation foreshadows the pickled, mean, and self-destructive man Capote would become after hollowing himself out in service of In Cold Blood: Another biographical film might have tacked on another hour, letting Hoffman go to town on the ravages of Capote’s decline. But we can see it all in this scene. We see his hunger for fame in the way Capote luxuriates in the flashbulbs on the red carpet. We see his soul-sickness in the way he stews in petty jealousy where at the start of the film he celebrated the publication of Lee’s book. Most of all we see his future in Keener’s eyes, in which she betrays not a flicker of disappointment or offense at Truman’s insult. She expected nothing better. Rather she extends a sympathetic pat on the back. She knows no insult he can dispense can match the abuse he’s going to inflict on himself.

Follow Michael on TWITTER and LETTERBOXD or join his weekly game of Movie Trivia on Zoom. Previous episodes of The New Classics here.