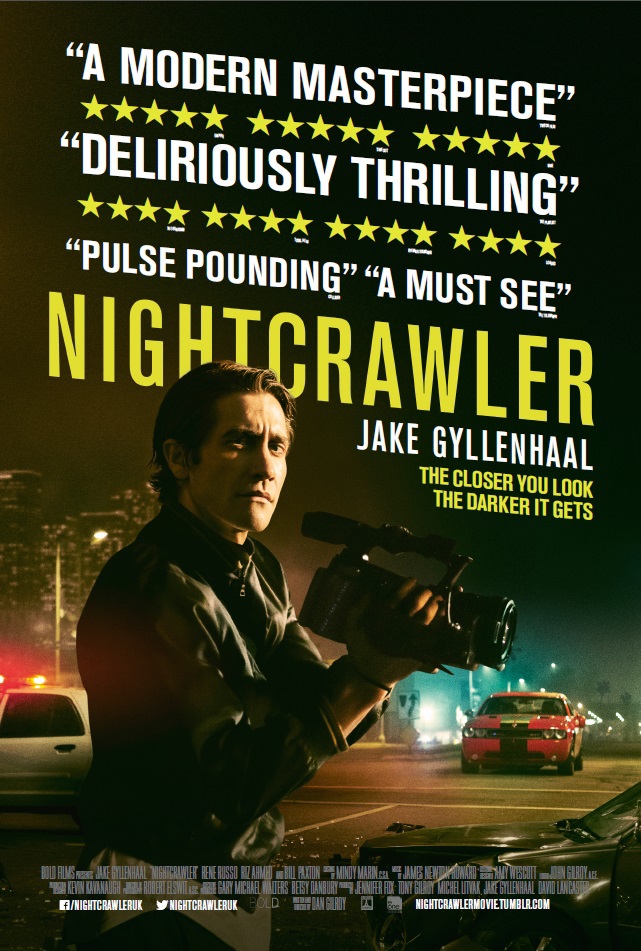

About once a decade we get a film set in the world of television that serves not just as a satire but a warning, asking us to take a look at the glaring problems in the way Americans get their information. Titles like A Face in the Crowd (1957), Network (1976), and Broadcast News (1987). It’s clear to me that the film to take up this mantle for this last decade was Dan Gilroy’s Nightcrawler (2014).

The trend in these stories does not inspire optimism. If the 2010’s spat up Jake Gyllenhaal’s Lou Bloom to represent it, am I ever terrified to meet the standard-bearer for the 2020’s...

Each of these films center around a harbinger of doom who exploits the system to great success. One can chart our growing disillusionment through the fates of these men. Face in the Crowd must’ve seemed pitch black in its day, but it ends with demagogue Lonesome Rhodes vanquished after his true toxic nature is exposed on live TV, an idea that is positively quaint today. Network’s “Mad Prophet of the Airwaves” Howard Beale is also destroyed but for much more cynical reasons: his rantings affected corporate profits. Broadcast News is ostensibly the lightest of these but it dares to have William Hurt’s idiot TV savant Tom end up on top of the world, although it does dilute the sting of that by having Tom bring on ethical Jane as his producer. (The film also denies him a symbolic romantic victory with Jane).

Which brings us to Lou Bloom. Lou doesn’t just succeed. He triumphs. Unequivocally. Those who opposed him are either dead or persuaded by his success to support him.

And more so than these other characters, Lou Bloom puts us, the audience, on the hook. Having a Lonesome Rhodes or Howard Beale indicts the gullible masses for being swayed by such figures but it also allows viewers a certain degree of distance. “I wouldn’t be taken in by these charlatans”, we think. Plus these men are aberrations. We might comfort ourselves that without them the system would basically function.

In Nightcrawler everything is irretrievably rotten from the start, allowing the likes of Lou Bloom to thrive like a case of black mold behind the evening news’ cityscape backdrop. He only ended up a stringer, selling grisly and racially inflammatory crime scene footage, because that’s what paid. It’s our bloodlust and racism driving that demand. Lou is ambition untethered. If Rene Russo’s TV producer said she needed heartwarming stories of unlikely friendships between animals, Lou would be breaking into the zoo to toss penguins into the tiger cage. But what Nina says is:

“Think of our news cast as a screaming woman running down the street with her throat cut.”

Lou isn’t lying when he calls himself a quick learner.

Which is not to say it’s all the system’s fault. Bloom is a sociopathic ambition vampire with hints of deep perversion churning below the grinning skeleton surface. His crimes cover everything from broken traffic laws to manslaughter. But it’s his threat to our institutions that is insidious and ultimately most frightening. It’s the kind of incremental corruption that Broadcast News identified in Albert Brooks’ famous tirade against Hurt’s character:

He will just bit by little bit lower our standards where they are important. Just a tiny little bit.

Scene: At the scene of a shooting

Nightcrawler pinpoints and isolates one such lowering of standards. When Bloom is first at the scene of a shooting at the home of a lower class family. He first sneaks into the house without permission while the victims are distracted, then, in a small but crucial moment, shifts one family photo on the fridge to be nearer to a bullet hole, creating the kind of punchy, obvious symbolism that is perfect for the fleeting attention span of the evening news.

Later Nina coos over the footage “That’s a great piece of tape!” and Gilroy has succeeded in making us disgusted at the ethical transgression. It’s a subtle act one break as the question becomes how far will Lou push the boundaries in pursuit of success. We know it won’t stop there, and sure enough, Lou’s manipulation quickly escalates to arranging dead bodies to orchestrating shootouts between cops and killers.

I’ve thought of that one shifted photo countless times since 2014. Nightcrawler shows how so many of our ethical rules aren’t rules so much as norms. They exist so long as everyone agrees they do, and as soon as one bad actor tromps over these invisible barriers we realize too late that the systems we thought were in place to punish such actions have atrophied from disuse or never existed in the first place. We end up watching as the Lou Blooms flourish while waiting for a moral comeuppance that never arrives.

Previously on Season 2 of "The New Classics"

Follow Michael on Twitter and Letterboxd or join his weekly game of Movie Trivia on Zoom.