There are many ways to talk about Phantom Thread. My favorite Paul Thomas Anderson production is, among other things, one of the best films about romantic love I've ever seen, looking at the way that loving another person is to willingly become vulnerable to them. To love is, in essence, to open ourselves up to the possibility of mutually assured destruction. The picture is also a canny dissection of the muse/artist relationship, one that illuminates matters of obsession, dynamics between the sexes, the luxuriant pleasure of touching silk, and gazing upon that which is beautiful. It's all that and much more, a multifaceted jewel of cinema about which I could write endless rhapsodies of passionate praise.

Still, for this piece, let's look at the aspect of the movie that earned one of its makers an Oscar (and a jet ski). I invite you all to peruse the costumes Mark Bridges created for Phantom Thread, a film which proves that lackluster fashion can be masterful costume design…

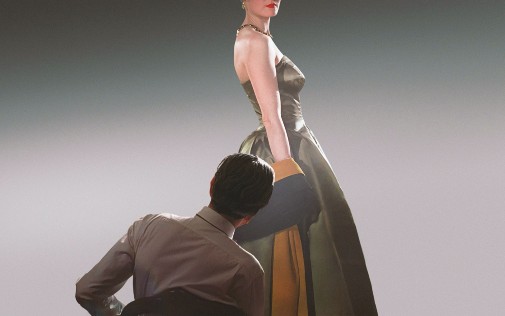

Phantom Thread tells the story of the unexpectedly twisted love affair between a controlling fashion designer and an immigrant waitress in 1950s England. Reynolds Woodcock is a renowned dressmaker whose clientele includes British aristocracy and foreign royalty. Woodcock is a war veteran and a mummy's boy who always carries something of the dead matriarch, be it a picture or a lock of hair, sown into the canvas of his suits. He's also an irritable asshole who can't so much as hear the scraping of a butter knife against toast without complaining about his spoiled routine. At the start of the film, we find him at the end of a particularly extenuated dress project and of an affair, a double dose of exhaustion that makes him drive to the countryside in search of relaxation. Instead of finding peace, he finds Alma.

She's a waitress from an unspecified European country whose confidence charms Reynolds on their first meeting. What follows suit is a strange relationship, one where the woman submits to the man's controlling whims, becoming his muse, model, and dress form. However, attempts at categorizing Alma as a helpless victim would be wrongfooted. She quickly proves to have a backbone that perhaps none of Reynolds' past companions ever had, falling into a delightfully sick game of power and submission with her whining couturier. What's perhaps most surprising about the plot is that their grotesque arrangement works, making for a love story with an unlikely happy ending.

With fashion so central to the character's world and even their geography -- most of the picture is set inside the House of Woodcock's atelier -- Phantom Thread was one of those movies that was predestined to win major raves for its costumes. Indeed, that's what happened. That said, among the celebration, there were also words of dissent. Many tweets, reviews, and entire write-ups talked about how the costumes Bridges designed were singularly underwhelming despite their narrative importance and pristine construction. The fashions of Reynolds Woodcock are hardly spectacular and certainly pale in comparison to the designs of such contemporary couturiers as Christian Dior, Cristóbal Balenciaga, or Charles James.

While I agree with those assessments, I think that calling Bridges' designs subpar because of their lack of cutting-edge style misses the point of the costumes and the film as a whole. Reynolds Woodcock may consider himself a genius worthy of worship and unquestioned obedience, but Anderson's vision doesn't necessarily share those delusions. The camera may rapturously observe the luxurious silks overlaid with Flemish lace, the precise construction of haute couture, and the erotic act of building a toile garment on someone's body, but its judgment of the finished pieces is never as straightforward. Upon seeing what was supposed to be a bridal tour-de-force, the only dress in the world, Reynolds himself describes his work as ugly.

The garments produced by the House of Woodcock aren't particularly chic, neither are they bold or innovative. On the contrary, they are the product of a rigid mind, one that loses itself in details and misses the bigger picture. These clothes are fussy and even a bit mumsy, their silhouettes closer to those of wartime frugality than the new tendencies brought on by Dior's New Look. Instead of full-skirted, the gowns are often narrow or bell-shaped, constrictive in their elegance, ostentatious but seldomly opulent. More than reminding us of the Parisian visionaries of the same period, they are more akin to the stodgy stylings of Norman Hartnell, Digby Morton, Edward Molyneaux, and other British-based designers.

In most movies, costumes are used to characterize the action on two fronts. First, they establish a time and place, a tone that lets the audience discover the world and aesthetic of the picture. Second, they serve to point out specificities about their wearers. Many times, great costume designers use clothing as a means of building characters in the same ways a screenwriter may use dialogue. In Phantom Thread, however, the showstopper costumes aren't used to characterize those who wear them, but the man who created the clothing in the first place. The garments of the House of Woodcock aren't there to reflect the interiority of their models, to establish the mood of the scene, or to dazzle us with spectacle. They are there to tell us who Reynolds Woodcock is.

That's especially evident whenever a garment falls outside the realm of Woodcock's control. Notice how his designs are obsessively symmetrical, but, when Alma surprises her lover with an unexpected homemade dinner, she wears a piece of her design with an asymmetrical silhouette. That choice shows her autonomy from Reynolds, her defiance, and is immediately regarded with distaste by the man. Another interesting moment where we can see how Alma and Reynolds play out their relationship in the form of clothing is the fashion show where she wears what is, essentially, a stylized version of her maroon waitress uniform and apron from their first meeting. Whether he has done it wittingly or not doesn't matter, Reynolds has immortalized Alma in his collection, he's used her as part of his craft. On her part, she refuses to be so easily used and reduced to a passive mannequin.

Phantom Thread shows us how avoiding the spectacle of high-fashion may be the right course of action, even when the production being outfitted is one centered on the fashion world. It's also a great example of how costuming can be as character-defining as the actor playing the role, with the caveat that it isn't always the one wearing the piece that's being defined.

Mark Bridges accomplishes all of this through the miracle of costuming, one so devastatingly perfect that I would go as far as to say that he's one of the most deserving victors in the history of the Best Costume Design Oscar.

Phantom Thread is available to rent from Amazon, Google Play, Apple iTunes, Youtube, and others.

We hope you enjoyed our mini-celebration of Paul Thomas Anderson's 50th Birthday.

- How Had I Never Seen Hard Eight (1997) by Claudio Alves

- PTA's Familiar Faces by Nathaniel R

- The New Classics: The Master (2012) by Michael Cusumano