Last week, we took a look at the cast of A Raisin in the Sun for the Almost There pieces. Among that quartet of fabulous performances, Sidney Poitier's Walter Younger stood out as the most overwhelming one, so full of energy that the claustrophobic set seemed incapable of containing him. This week, we're again exploring the filmography of the first Black man to win the Best Actor Oscar, giving him a solo opportunity to shine. You could actually do an entire miniseries about the many times Poitier might have come close to an Oscar nomination and failed: A Raisin in the Sun, Edge of the City, Porgy and Bess, A Patch of Blue.

Today, however, we'll be looking at Poitier's 1967 Oscar bid, when the actor starred in three hits, two of which went on to be nominated for Best Picture. Of them, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night went on to win the big award and features what is probably the best performance of Poitier's career…

In The Heat of the Night is a hybrid of crime thriller and message movie, a procedural that unfurls a mystery in the same breath it tries to confront racial injustice. Some consider it a stone-cold classic, a courageous project that dared to deal with heated topics at a time when Hollywood would rather escape from the social schisms of the real world rather than represent them. On the other hand, others see it as a reactionary movie with good intentions but plenty of clumsiness too. I fall somewhere in the middle of those reactions, neither finding it a masterpiece nor an utter failure. Some aspects of it work like gangbusters, that's for sure, among which the cinematography of Haskell Wexler deserves particular praise, for example.

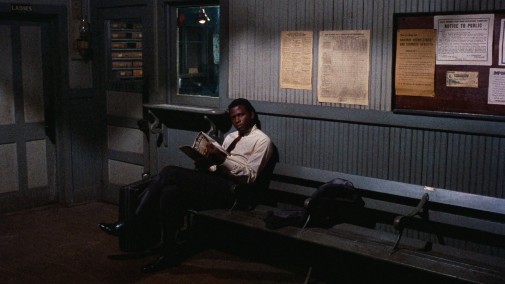

Through his lensing, we discover the small town of Sparta, Mississippi, as a shadowy place where the heat is unbearable and the night vibrates in deep blues. It's during such a night that we are introduced to our protagonists, a hot-headed local police Chief called Bill Gillespie and Mr. Virgil Tibbs. The latter one is the focus of our analysis, an African-American homicide detective from Philadelphia who's passing by Sparta on his way home. When we first see him, he's sitting on the platform, peacefully waiting for the next train, when he's spotted by another cop and promptly arrested for the crime of being Black. Accused of a murder he didn't do, stoic and preternaturally controlled, Tibbs goes through the indignancy of the arrest with quiet acquiescence, letting his fury simmer beneath a placid mask.

As the two law officers meet and the Philadelphian is made to help the Spartan police with a murder investigation, the tension between Gillespie and Tibbs is almost unbearable. In terms of body language, it's hard to miss how Poitier becomes increasingly rigid, each new insult weighing him down and intensifying the fury that shines in his eyes. If there's one thing that characterizes actor's approach to the character in these early scenes is that sense of contained rage. Tibbs may swallow down his responses to the racist nonsense that's inflicted upon him, but he isn't happy about it. Watching him is like watching a rope getting twisted, each new twist tightening it more and more. It's just a matter of time before all that tension is released and the rope breaks.

That release of accumulated tension comes in fits and starts with Tibbs trying to downplay how much the situation is affecting him. There's the iconic line "They call me Mister Tibbs!" and the famous slap that was heard around the world, but we never sense that the detective is losing control of himself. Such a register of perpetual self-repression is one hell of an acting challenge, for it asks a performer to outwardly close themselves off but, at the same time, telegraph the interior struggle to the audience. Poitier does it impeccably and adds many personable details to his characterization, dodging the bullet of one-note monotony. Notice the glimmers of pride Tibbs shows, how his stance changes when dealing with Black people instead of white bigots, how his hands move across a dead body with the ease of a confident profession whose gestures have become automatized thanks to repetition.

It's an intelligent performance that is made out of those little details as much as it is defined by Poitier's magnetic presence. The way he holds his body and catches the light with his eyes, his cool detachment, all of it transmits a sense of authority that requires only that the actor exists in front of the camera. Comparatively, Rod Steiger's Chief Gillespie is a mountain of mannered ticks, a filigreed construction of non-stop business and showboating that's admirable in its own way but contrasts starkly with Poitier's approach. I prefer the precise nature of Tibbs to the undisciplined ham of Gillespie, but it's easy to understand why one would want to reward both. That's what the Golden Globes did when they nominated the two performers for the Best Actor in a Drama award. Unfortunately, the Oscars didn't follow suit and only recognized the white star of In the Heat of the Night.

Rod Steiger won the Best Actor trophy that year, while Poitier was completely ignored, having also been snubbed for his solid work in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner and the box office hit To Sir, With Love. To understand this awards race in great detail, I recommend reading Mark Harris' Pictures at a Revolution but, suffice it to say, Poitier suffered both from vote-splitting between his big movies and a period of societal upheaval that saw the Academy respond in their usual reactionary manner. Some would say that awarding In the Heat of the Night Best Picture is part of that too, for the film ends with amicable peace between the two men, promoting the age-old Hollywood myth that racism is a problem of the individual that can be solved one interracial friendship at a time.

Still, Poitier's Tibbs is an Oscar-worthy achievement. If for nothing else, he deserved the trophy for the way his indignant fury still haunts the film by the end, smothering some of the movie's self-congratulatory noxiousness even as Tibbs exits the story with a smile on his face.

In the Heat of the Night is available to stream on Amazon Prime and IndieFlix. You can also rent it from Apple iTunes, Youtube, Google Play, and others.