Daniel Walber's series on Production Design. Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

First Cow is a mossy and melancholy tragedy. Kelly Reichardt makes the failure of her protagonists clear from the start, showing us their skeletons before introducing them in the flesh. There’s a morbid air to everything that follows, though it’s softened by an atmosphere of tremendous beauty. It’s the best ASMR video of the year.

First Cow is a mossy and melancholy tragedy. Kelly Reichardt makes the failure of her protagonists clear from the start, showing us their skeletons before introducing them in the flesh. There’s a morbid air to everything that follows, though it’s softened by an atmosphere of tremendous beauty. It’s the best ASMR video of the year.

Cookie Figowitz (John Magaro) and King-Lu (Orion Lee) clearly think that they are in a land of endless possibility: Oregon Country in the 1820s. Decades before a settled border, the USA and the British Empire “jointly occupied” the Pacific Northwest, in accord with an 1818 treaty agreement that did not even acknowledge the presence of indigenous people.

This is the context for King-Lu’s utterly false observation:

This is still new - more nameless things around here than you could shake an eel at… History isn’t here yet.”

Cookie disagrees, saying that to him “it seems old.” It’s a crucial early conversation, which sets up some difference in their characters. But it’s hard to shake the notion that these two are really just opposite sides of the same coin. Both men taken in by the myth of a lush, ancient landscape without names or living languages, densely forested but devoid of human culture - and with riches ripe for the taking by the common settler, if only he gets there in time.

And they never learn otherwise. Cookie and King-Lu dream of beaver glands and hotel bakeries until their last, somnolent breaths. As such, this mythology must be busted elsewhere, in large part via the work of production designer Anthony Gasparro and art director Lisa Ward. The colonial filter through which most of First Cow’s characters see their environment is quietly dismantled through an artful exhumation of colonial architecture.

Take, for example, the arrival of the titular cow. The scene begins with some close-ups of baskets, upon which local indigenous women are cracking nuts (see what I mean about ASMR?). It’s a symbol of, among other things, a continuity of local craftsmanship that stretches back well before the arrival of the settlers. There are plentiful names, languages, cultures and histories already present.

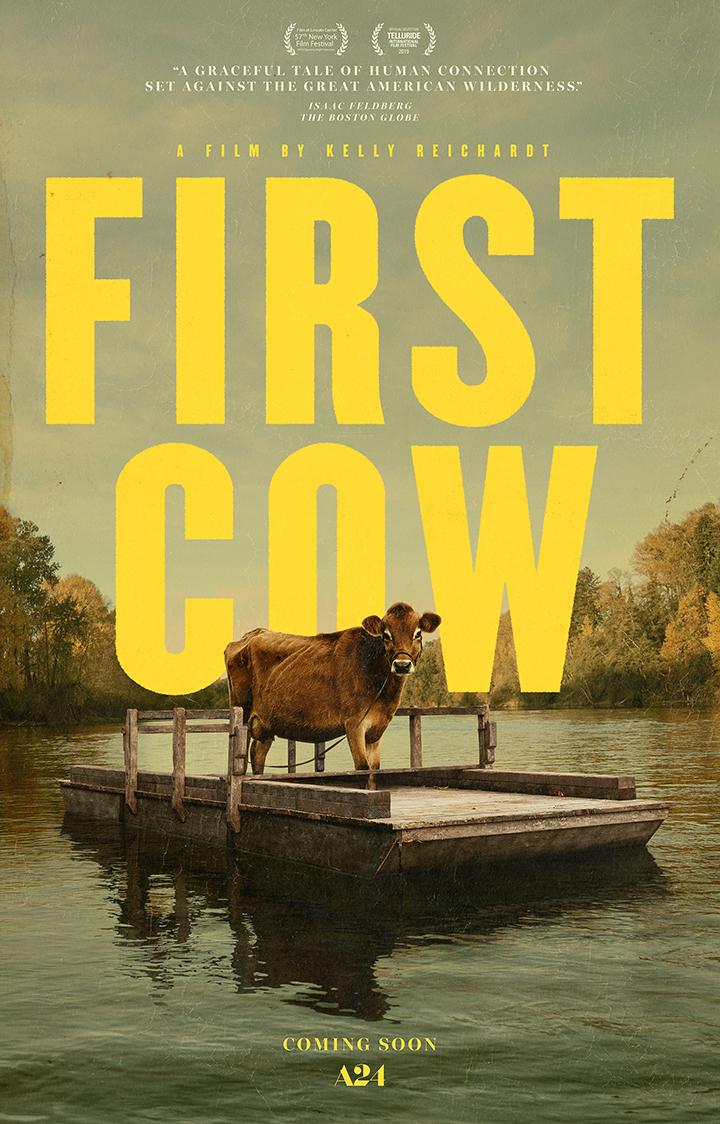

Then Reichardt cuts to the dock. It’s small and nondescript, only big enough to handle one or two cows. Granted, it only needs to support the one. To King-Lu and Cookie, this first cow is a sign that they’ve not yet missed their moment, that this is still a time of “before.” But to the women on the shore, the landscape has already irrevocably changed.

It is even more obvious in the fort, of course. The company flag is a clear symbol of the arrival of imperial commerce. The architecture itself poses questions. When looking at a wall made of sticks and a cabin made of logs, do you focus on the unfinished material or the military form? Is this a structure of “before” or “after”?

The oddest example is one of the nearby shacks, fashioned from local wood that hasn’t even been stripped of its bark. It looks almost like a natural outgrowth of the forest. Except, of course, for the fact that it’s not. It’s a striking metaphor for the falseness of a settler colonialism that will yield generations of “mountain men,” with their endless claims of male stewardship and ownership of the “virgin” landscape.

Still, King-Lu and Cookie might look at these shacks and see the possibility of their own entrepreneurial success. But it looks quite different in the home of the Chief Factor (Toby Jones), whose furniture makes Cookie seem like little more than a servant. And it is tragically poetic that his last-ever bake will be a clafoutis for which he will never be paid, on command of the wealthiest man in town.

King-Lu, meanwhile, is treated as a total non-entity. His opinion on the beaver market is met with confusion and silence by the Chief Factor and the Captain (Scott Shepherd). Of course, this does not prevent the Chief Factor from waxing poetic about the Chinese market. To him, China is yet another abstraction of imperial capitalism. King-Lu, standing in front of him in North America, cannot exist.

The Chief Factor’s interiors are the final proof that there is nothing “before” about Oregon Country, even in the 1820s, nor is it a place of openness and possibility. In fact, things only get worse. After the border was sorted out in 1846, the Provisional Government of Oregon wrote its white supremacy into law by banning the entry of Black people into the territory. In 1858, an Exclusion Law explicitly denied the right to vote to Chinese residents, the first of a long series of “exclusion laws” that federally prohibited Chinese immigration 1882 and banned Chinese property ownership in Oregon in 1923.

By then, Cookie and King-Lu’s dreams would have been long dead, but it puts their folly in even starker perspective. Getting the milk for free under cover of night can bring in a fair amount of cash, but would never be enough for King-Lu and Cookie to buy a royal cow - so to speak. The cow and her milk have already been commodified, the independent artfulness of Cookie’s biscuits notwithstanding. At the end, when the Chief Factor puts his prize cow in a pen, he does little more than make this explicit. Cookie and King-Lu’s small-time dreams were never really welcome in Oregon.