1991's The Silence of the Lambs won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, thus becoming the only horror movie to ever conquer that much-coveted prize. Still, overall, the film seems to owe more to the crime thriller, the police procedural and investigative manhunt than it does to the horror genre. However, one element plunges it right into the depths of cinematic nightmares. It's a character so malevolent that it often feels larger than life, like a primordial evil closer to the divine than to the human. We're talking about the monster that tops the AFI's greatest movie villains list, the role that earned Anthony Hopkins his Oscar and made us never look at Fava beans the same way ever again – Hannibal 'The Cannibal' Lecter…

Before Hopkins took on the iconic part, another actor had tried on the shoes of the most famous character ever conceived by novelist Thomas Harris. In 1986, director Michael Mann made his own adaption of a Harris' novel, The Red Dragon, rebaptized as Manhunter for the big screen. As in The Silence of the Lambs, Mann's picture positions Lecter at the periphery of the story, a Mephistophelean consultant that aids a young investigator in the capture of another homicidal maniac. No matter how central he may be to the picture's general atmosphere of stifling moral degradation and virulent violence, Lecter is a supporting player, confined to the insides of a white cell from which he spews venomous words like the diabolical snake he is.

In the same way his film differs from The Silence of the Lambs in terms of tone and intent, so does Brian Cox's Hannibal differ from Hopkins'. His version of the monster isn't as steeped in theatrical sophistication as the latter portrayal, presenting a Hannibal that's more physically menacing but also less cerebral in his evil-doings. Moreover, while Hopkins' Oscar-winning performance makes Lecter into something inhuman, a reptilian beast of other-dimensional provenance, Cox's take is more grounded. The Hannibal of 1986 is frighteningly believable as a serial killer that could exist in our world, a brutish presence that's not as ethereal as his 1991 counterpart but just as unsettling.

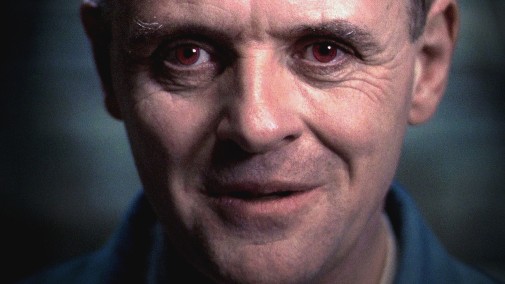

That being said, if asked to name the best screen version of this villain, I'd have to choose the one Jonathan Demme lensed in The Silence of the Lambs. Cox glowered from his cage like a trapped animal, hungry for prey that's out of reach, but Hopkins plays Hannibal like a predator that already has its squirming meal pierced atop a pointy claw. Throughout his conversational games with Clarice Starling, he's like a cat pawing at a helpless mouse, playing with his food. It's entertaining to watch, but it's also terrifying, as Hopkins makes our skin crawl in survivalist revulsion at the same time we are enthralled by his every arsenic-laced word, every arrogant smirk and sharp smile.

While he wouldn't have been my choice for the Best Actor trophy, it's impossible to begrudge the Welsh thespian his accolades since his take on the role is so undeniably magnificent. The same cannot be said about his reprisals of the part, in Ridley Scott's flotsam Hannibal and Brett Ratner's underwhelming Red Dragon. There are some things to cherish about the second movie, but the Scott helmed abomination is more difficult to defend, in part because its source material is so uncontrovertibly mediocre. After the success of The Silence of the Lambs movie, Thomas Harris decided to capitalize on the popularity of his great villain, writing new sequels and prequels that lose what made his early works special.

When reviewing the gangrenous disaster that was Harris' Hannibal Rising, New Yorker critic Anthony Lane wrote down the five essential conditions that must be fulfilled for a Hannibal Lecter story to work. "1. Lecter must be incarcerated. 2. He must be in America. 3. He must be peripheral to the plot (the capture of another killer), however central he is to the atmosphere. 4. He must attract the professional interest of a woman. 5. He must be as insoluble as Iago." It's possible to argue against some of those tenets, especially when considering a certain TV show, but the fifth necessity seems, to me, like a cosmical truth that's as undeniable as the rising sun. For Hannibal to work, he must be insoluble, incomprehensible, a mystery that's left unsolved.

That's the main reason why Hannibal and Hannibal Rising, both novels and movies, so flagrantly fail. One shouldn't try to explore why Hannibal Lecter is Hannibal Lecter, he simply is. If you love the villain you saw in The Silence of the Lambs, I besiege you to avoid watching the Ridley Scott catastrophe as well as the 2007's adaptation of Harris' prequel. Both movies are so bad they the preceding works feel worse in retrospect. Hopkins' first portrayal of the cannibal is a being of all-consuming evil, a disease upon this world which sickens our souls the longer we gaze into its abyss. On the other hand, the protagonist of Hannibal Rising, now played by Gaspard Ulliel, is a nasty-minded whinny avenger with a taste for human flesh and a kill list comprised of people so venal that they make him look valorous in comparison.

Luckily for the fans of the villain, another screen version was to come, overshadowing the mediocrity of post-1991 Hannibal Lecter and offering audiences a fresh take on the character. Bryan Fuller's Hannibal is a twisted game of cat and mouse curdling into a horrifying queer romance. It's also one of my favorite TV shows. Played by Mads Mikkelsen, the killing psychiatrist is central to the plot, mostly out of prison and sometimes traveling through Europe, violating three of Lane's tenets in a fell swoop. However, he's never fully explained, his brains never unspooled for us to see the reasons behind the monster's monstrosity.

If anything, this Hannibal manages to be more alienating than his predecessors, fully embracing the epicurean abandon suggested in the source material and taking it to extremes so ignoble they go beyond comprehension. He's also impeccably dressed and horny for Hugh Dancy, which makes him fun to watch and weirdly sympathetic. Demme and Hopkins made us squirm away from the screen in dazzled fear, but Fuller prefers to seduce his spectators. Before we know it, we've fallen into the spell of Mikkelsen's Hannibal and are more disgusted at ourselves than at his cannibalistic ways. Revulsion and lust, two very different ways to interpret Hannibal Lecter, both successful and worthy of our attention. Which one do you prefer?

The Silence of the Lambs and the three seasons of Hannibal are available to stream on Netflix and Amazon Prime. You can easily find the other screen iterations of Hannibal Lecter online, though Manhunter isn't available to stream anywhere at the moment.