As a general rule, remakes don't represent a particularly respected type of film among cinephiles. Concerns about lack of originality abound, as do questions of necessity and the way remakes can lead to the obscuration of older movies. That being said, to characterize every remake as a mercenary minded waste of time isn't fair to the filmmakers involved. Moreover, it can result in the unfair dismissal of interesting cinematic propositions. Remakes can recontextualize past narratives, respond to aesthetics of yore and comment upon them, reinterpret texts and revitalize forgotten styles, deepen pre-established themes or even make us look at a classic through new eyes. They can also highlight the specificities of different artists' visions, exposing how their particularities shape the same raw material. Not all remakes are good, but we can say that about every kind of film project.

Some directors have shown a particular aptitude for this type of project, like Luca Guadagnino with A Bigger Splash and Suspiria. Still, we're not here to talk about that epicurean delight or the transfiguration of Dario Argento's post-Giallo masterpiece. Our subject, today, shall be Martin Scorsese and his mastery of the remake…

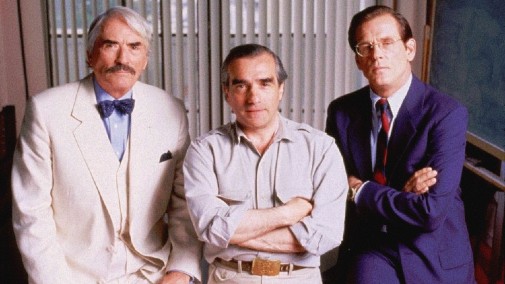

1962's Cape Fear, directed by J. Lee Thompson, is a classic of neo-noir cinema, playing with notions of psychological warfare, paranoia, and a sense of domestic bliss rudely violated by a ghost from the past. Robert Mitchum embodied that early movie's haunting villain, delivering one of his greatest star turns as a demented rapist hellbent on revenge after getting out of prison, while Gregory Peck was the lawyer whose family is targeted by the criminal. Tightly paced and strikingly scored, the movie's good reputation and lasting influence are amply justified, though some of its morality is a bit too neat, its suspense too mechanically perfect. There are no grey zones in the first Cape Fear, no risky form, no murky waters for the audience to thread to as it experiences Candy's malevolence. It's great, but in a controlled manner that leaves little space for genuine surprise or shock.

1991's Cape Fear, directed by Martin Scorsese, is a different beast altogether. While both movies are putatively adapted from John D. MacDonald's novel The Executioners, the later project owes a lot to its predecessor, even recasting some of its main actors in showy cameos. In some ways, Scorsese's reimagining feels like a response to the original, a challenge almost. It's a savage response, in any case, one with sharp teeth and someone else's blood on its mouth. Instead of precise thriller mechanics, the younger Cape Fear is a lurid spectacle, as wild and savage as its slippery villain, now played by Robert DeNiro at his most unhinged. That's not a dig at the actor, by the way, since it's only right that he goes to extremes when his director is so gloriously off the deep-end, drunk with a cinephile's love and a mad genius' self-assurance.

Scorsese throws everything at the wall with his direction of Cape Fear. We get the sense that he's not even seeing if something sticks, he's just having fun and asking us to join in. Even so, part of his mastery comes from the knowledge of when to stop, when to back down, and put an end to his formalistic folly. Consider the twelve-minute pas de deux of sexual precociousness and predatory manipulation that is the first scene shared between De Niro and Juliette Lewis as the lawyer's teenage daughter (now a character instead of an anonymous archetype). You can cut the tension with a knife, and it's not just because of the actors. It's thanks to the stillness of the camera and the editing, the movie holding its breath, waiting for some horrible thing to happen. Faced with such breathless contention, the audience has no choice but to become restless.

The second Cape Fear is the perfect example of a good remake. It's not only a riveting piece of cinema, but it also illuminates some of the original's best qualities by showing another, different but equally valid, approach. Scorsese did a similar thing in 2006 when he remade the Hong Kong crime thriller Infernal Affairs as the Oscar champion The Departed. That movie takes an already complicated plot and makes it into a byzantine labyrinth, decentering the original protagonists and adding twists and turns. At the level of direction, what's most impressive is how Scorsese weaponizes the audience's disorientation and allegiance to the players, making for an experience that's more visceral than the original even as it is less character-based. Again, two approaches, both valid but beautifully unalike.

1991's Cape Fear is streaming on fuboTV, DirecTV, and Showtime. As for The Departed, you can find it on fuboTV and HBO Max. Are you a fan of these Scorsese-helmed remakes?