Daniel Walber's series on Production Design. Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Yul Brynner, who we're celebrating this week for his centennial, was in a lot of very expensive movies. His biggest year was 1956, with The King & I, Anastasia and The Ten Commandments - a combined budget of over $20 million. But there were plenty to follow. Studios saw Brynner as a generic racial and ethnic “other,” which got him cast in all sorts of bloated historical, international, orientalist pictures. Which also means, of course, that many of his movies are entirely worthy of consignment to the dustbin of Hollywood history.

Yul Brynner, who we're celebrating this week for his centennial, was in a lot of very expensive movies. His biggest year was 1956, with The King & I, Anastasia and The Ten Commandments - a combined budget of over $20 million. But there were plenty to follow. Studios saw Brynner as a generic racial and ethnic “other,” which got him cast in all sorts of bloated historical, international, orientalist pictures. Which also means, of course, that many of his movies are entirely worthy of consignment to the dustbin of Hollywood history.

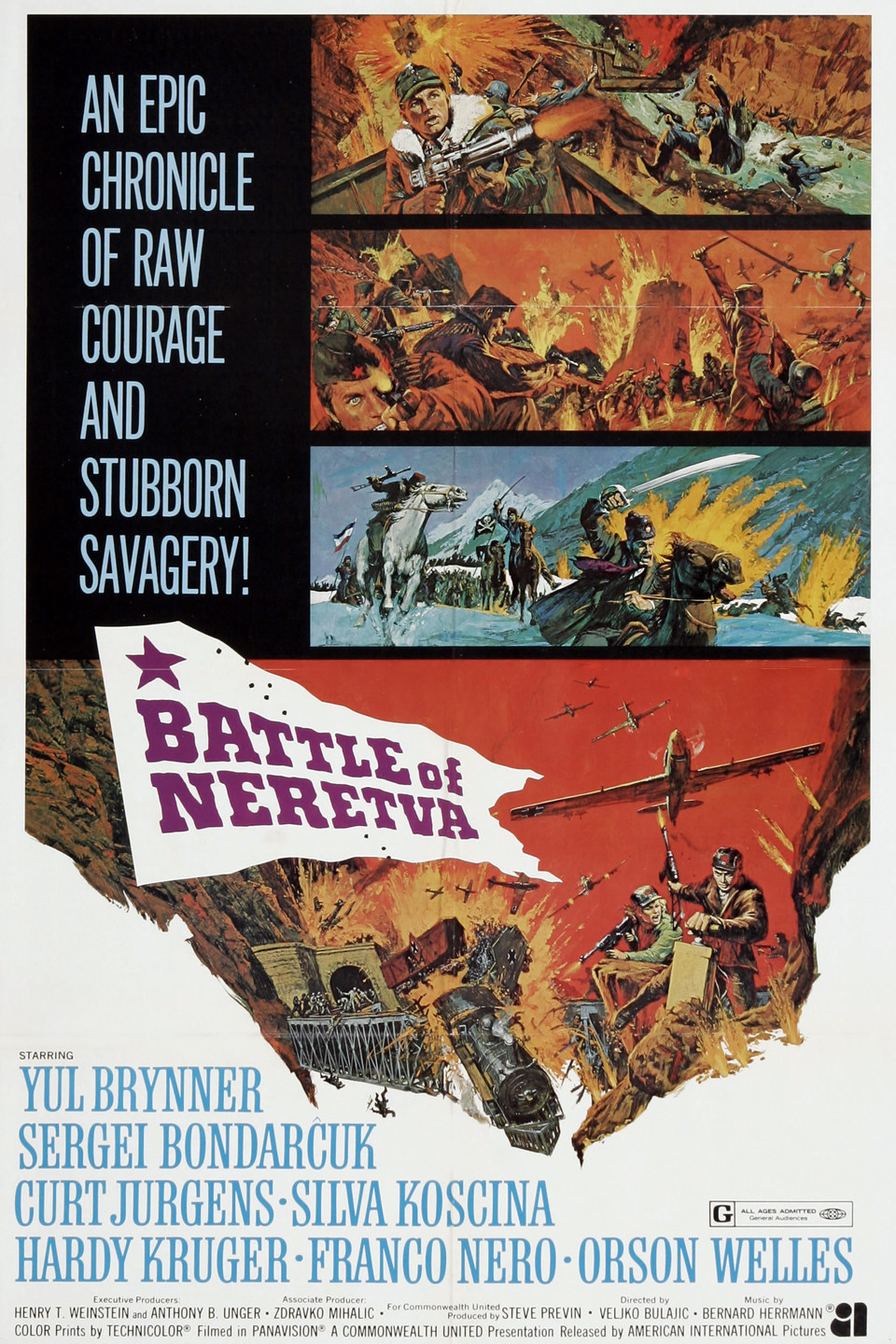

Intriguingly, though, he did occasionally work beyond Hollywood. In the late 1960s he joined Orson Welles, Sergei Bondarchuk, Franco Nero and Curd Jürgens in Yugoslavia for The Battle of Neretva. A World War Two Partisan film directed by Veljko Bulajić, a Partisan veteran himself, it ranks as the most expensive production in the history of Yugoslavia - and potentially in Brynner’s career, as some estimates push it into Ten Commandments territory...

The Battle of Neretva was a passion project for Yugoslavia’s movie-obsessed Communist leader, Josip Broz Tito. In a way, it’s his answer to the Soviet War and Peace, then the most expensive movie ever made anywhere. That’s certainly why Bondarchuk was cast. But unlike War and Peace, The Battle of Neretva is neither a literary adaptation nor a 19th century period piece. It’s a representation of recent memory, a campaign that Tito himself fought against the Nazis in 1943 - though he resisted the urge to put himself in the movie.

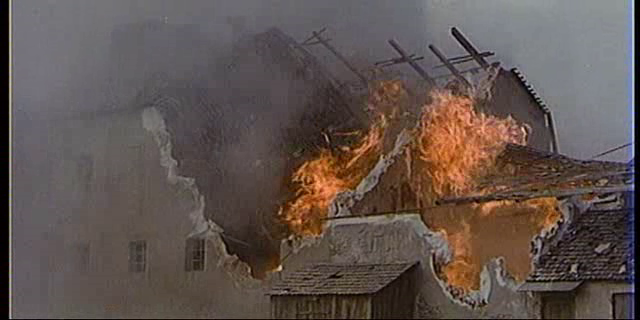

It is also one of those rare movies that makes you feel as if you’re watching someone set piles of money on fire.

The plot, briefly, follows a German offensive in early 1943. At the end of February, Tito decided to make a stand in Prozor and had all of the bridges over the Neretva River destroyed. This was followed by a week of fighting, maneuvering, and even negotiations. The result was a total shift in strategy by Tito, who decided that his forces did need to cross over the now-bridgeless Neretva.

Simple enough. To bring it to life, Bulajić and the production design team, led by Dušan Jeričević and Vladimir Tadej, would go about building and burning two entire villages.

Brynner plays Vlado, a Partisan engineer. (His fellow Hollywood import, Welles, plays a sinister Nazi-allied Chetnik senator.) Vlado will be responsible for the demolition of the bridges, an order that shocks many of his compatriots. It also may very well have shocked the movie’s crew, who would have to capture the actual demolition of this bridge:

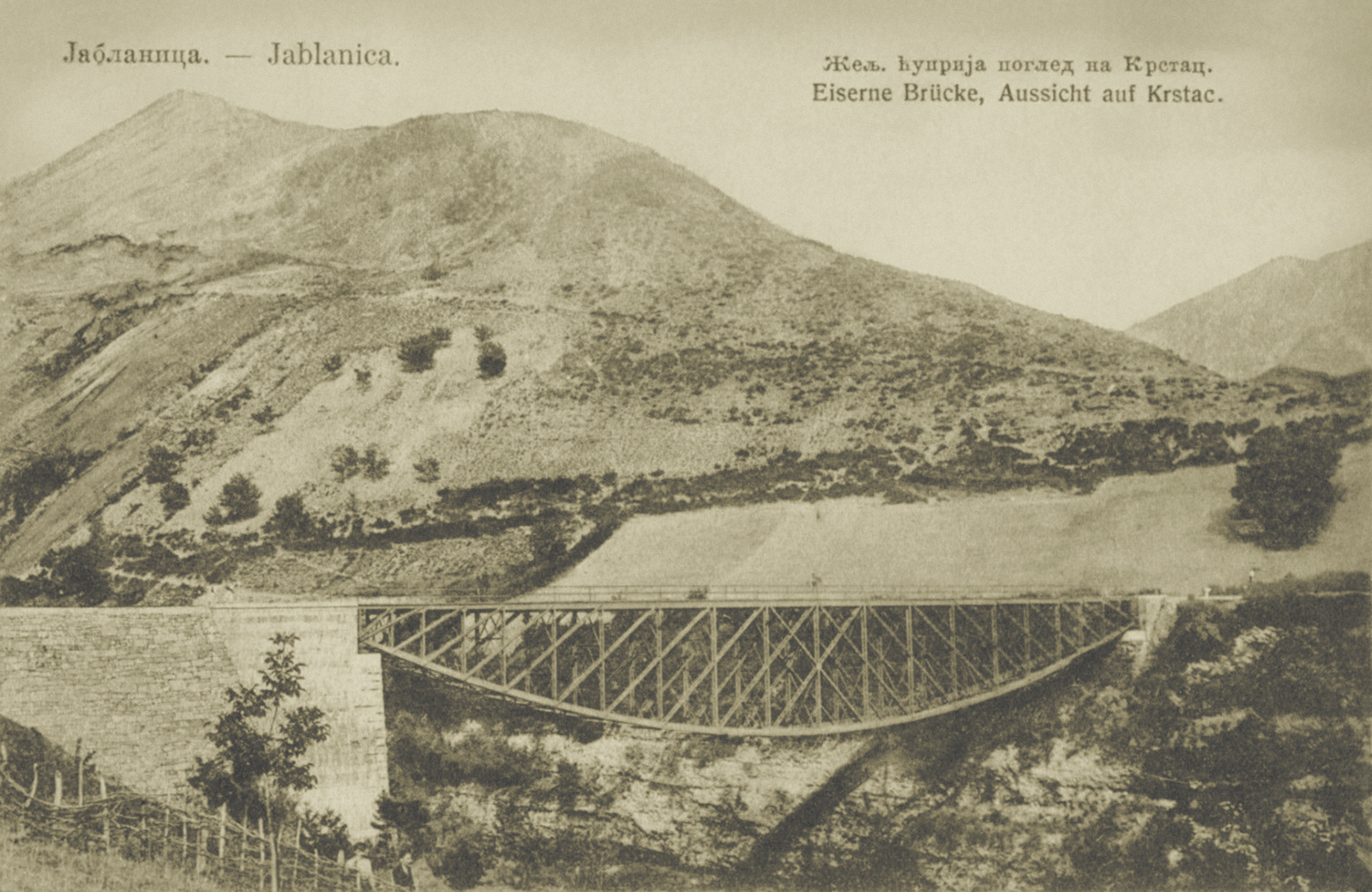

Or, well, not quite that bridge. The story goes like this: the bridge in question was in the town of Jablanica, now part of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The original bridge was built in the 1880s. Tito’s Partisans demolished it in early March, 1943. It looked like this:

Then, five months later, the Nazis built a new one. It stood until 1968, when it was blown up by the crew of The Battle of Neretva. But there was far too much smoke to get a good shot, so they rebuilt the bridge themselves and blew it up again. Apparently there was still a lot of smoke, so the version in the film is a composite of the real demolition and miniatures that were shot later.

Honestly, it’s one of the best scenes in the movie.

They get everyone across, climb the other side, and set it on fire again. Not too long after that, the credits roll.

In 1977, nearly a decade after the movie, Yugoslavia built a new bridge. But they left half of the rebuilt and re-demolished German-built 1943 bridge dangling off the side of a cliff. And in 1978, Tito inaugurated a brand-new memorial and museum on the site. Its logo uses the image of the broken bridge, though without a curved arch - it looks like the one from the movie, not the one that was actually demolished in March of 1943.

Does that matter? Perhaps if you visited Jablanica before 1943. Perhaps if you were one of the Partisans who used its wreckage to escape the Nazis and Chetniks. But that’s precious few people alive today. And the Bridge on the Neretva is hardly the only military heritage site that has been replaced with a movie in the minds of the public. How many people who visit the Alamo are really there to visit the John Wayne version in their heads?

The remains of the replacement bridge are now part of a heritage landscape, managed as both shrine and tourist attraction. The museum’s website also advertises the preserved Chetnik bunker across the river and the bizarre ruins of the 1978 monument to Tito over in Prozor. And there are the Stecci, elaborate medieval tombstones that were added to the World Heritage List in 2016. The Stecci also appear in The Battle of Neretva, perhaps as a gesture of multinational Yugoslav patriotism - these cemeteries are both Catholic and Orthodox, and mostly in majority-Muslim Bosnia.

These locations, taken together with the movie, invite visitors to craft their own interpretation of the past. The Battle of Neretva didn't represent history, it influenced it - narratively, even geometrically shaping the way these events are remembered.

But all films do that, even those that leave the physical landscape untouched. Perhaps blunt instruments like The Battle of Neretva are simply helpful reminders of that power.