Daniel Walber's series on Production Design offers a digestif for our Shelley Winters festival. Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Does it matter to you if a disaster movie is realistic? This is an honest question. How solid is your suspension of disbelief when it comes to airplane explosions and burning buildings, tsunamis and earthquakes? Do you sit on the couch fact-checking on your laptop while expensive catastrophes unfold on your TV?

Does it matter to you if a disaster movie is realistic? This is an honest question. How solid is your suspension of disbelief when it comes to airplane explosions and burning buildings, tsunamis and earthquakes? Do you sit on the couch fact-checking on your laptop while expensive catastrophes unfold on your TV?

I ask this because I was surprised to learn how much the team behind The Poseidon Adventure cared about accuracy. Paul Gallico, who wrote the original novel, was inspired by an actual trip on the Queen Mary he took in 1937, during which the ship turned on its side. And he did plenty of research to make sure it was possible for an ocean liner to be flipped entirely upside down by a rogue wave.

Director Ronald Neame and production designer William Creber were equally concerned. By the time The Poseidon Adventure went into production, the Queen Mary had begun a long retirement docked in Los Angeles. Much of the film was shot on the real ship, including this pleasant glimpse at the deck...

There’s Shelley Winters and Jack Albertson as Belle and Manny Rosen, a couple of Jewish grandparents on their way to Israel to meet their brand-new grandchild. Later, these two will become crucial to The Poseidon Adventure’s attempt at allegory, like a spiritual sequel to Ship of Fools. But for the moment they’re just another detail in Neame and Creber’s meticulous construction.

So meticulous, in fact, that the interior sets back at the Fox Studio were built from archival photographs and the Queen Mary’s original blueprints. Everything was to be as precise as possible, presumably to make the horror seem all the more real.

And, frankly, it works. As a feat of engineering, the ballroom set is astonishing. Creber and set decorator Raphael Bretton would have deserved their Oscar nomination for the central sequence alone, a nightmare New Year’s Eve party with just enough flying tinsel to overwhelm the audience.

There’s even a falling piano!

That the tables and chairs remain stuck to the ceiling, even after the ship has fully rolled over, may seem like a rush into the surreal. Yet this was yet another well-researched detail, as cruise ships often bolt down the furniture in case of rough seas.

The thing is, there’s still half a movie left. We’ve had a realistic disaster, now what? From here, the script positions the Reverend Scott (Gene Hackman) and his small band of survivors as stock characters in a vague allegory of faith and self-empowerment. The production design follows as best it can, abstracting and escalating the vibe. Does it make much sense? Absolutely not. But it’s a hoot to watch a Jewish grandmother climb an enormous Christmas tree, regardless of whatever bizarre point the film is trying to make about the doomed and sheepish crowd below.

And she makes it up just in time.

The water bursts into the ballroom, drowning everyone who refused to listen to Reverend Scott. From here, the film’s focus shifts from the ship as a whole to this small group of survivors, whose journey will get stranger with every step.

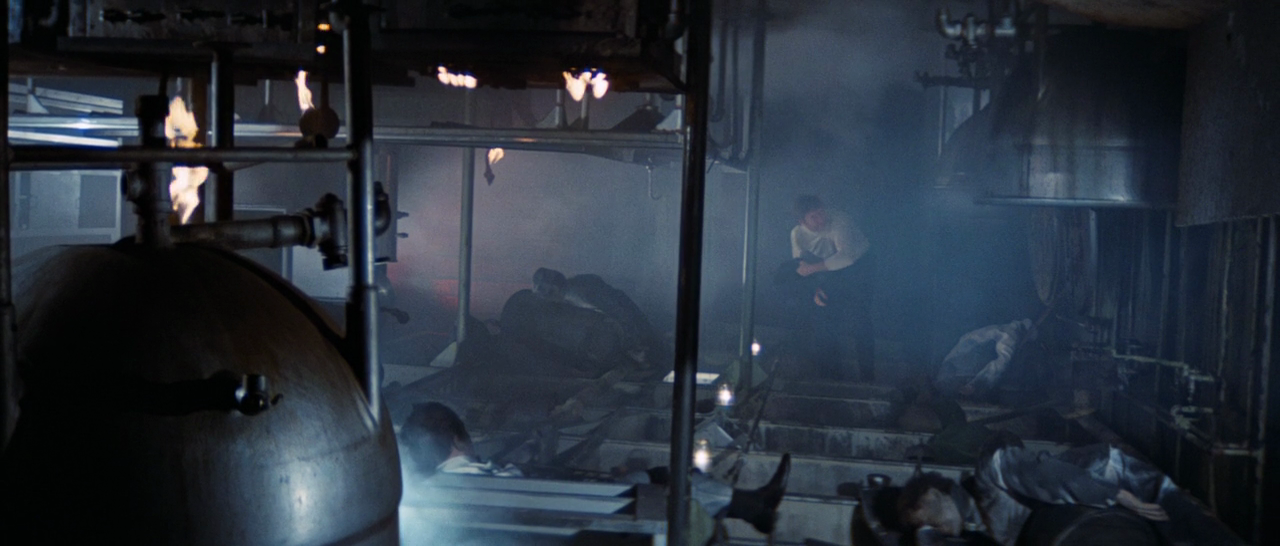

The next obstacle is the kitchen, a dungeon-like chamber littered with burnt corpses and gas flames. Belle takes one look at the scene and panics, refusing to go any further. Manny manages to get her through, but it’s hard not to read her reaction as a reference to another, much more real death chamber.

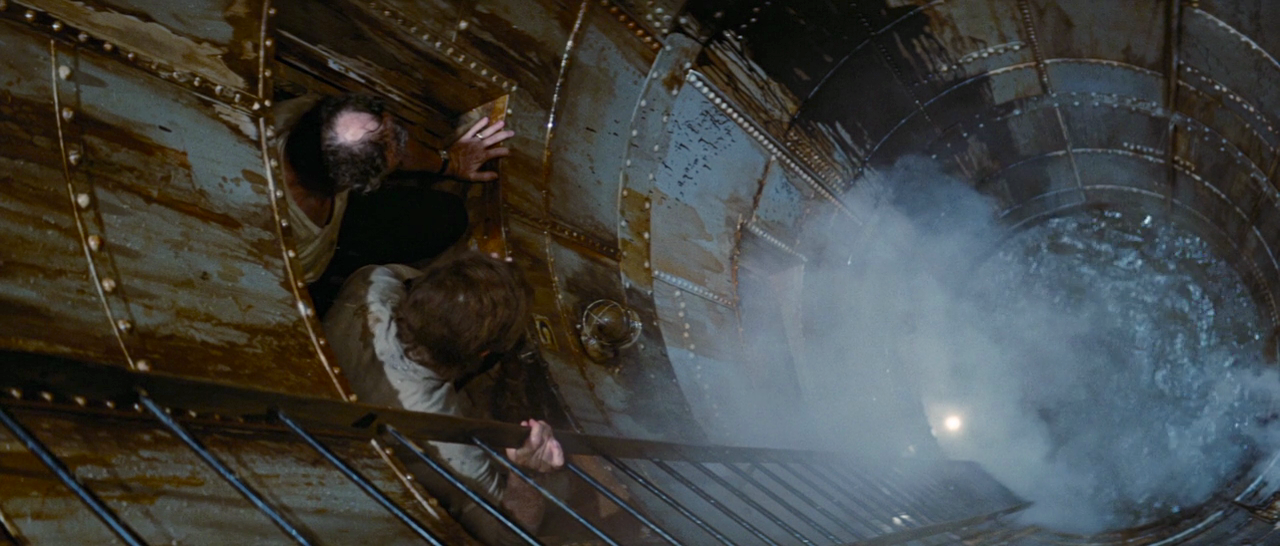

Next is an internal shaft, a forbidding column in the ship’s normally hidden underbelly. It’s the first set that offers absolutely no grounding in the familiar. It looks like something out of a video game.

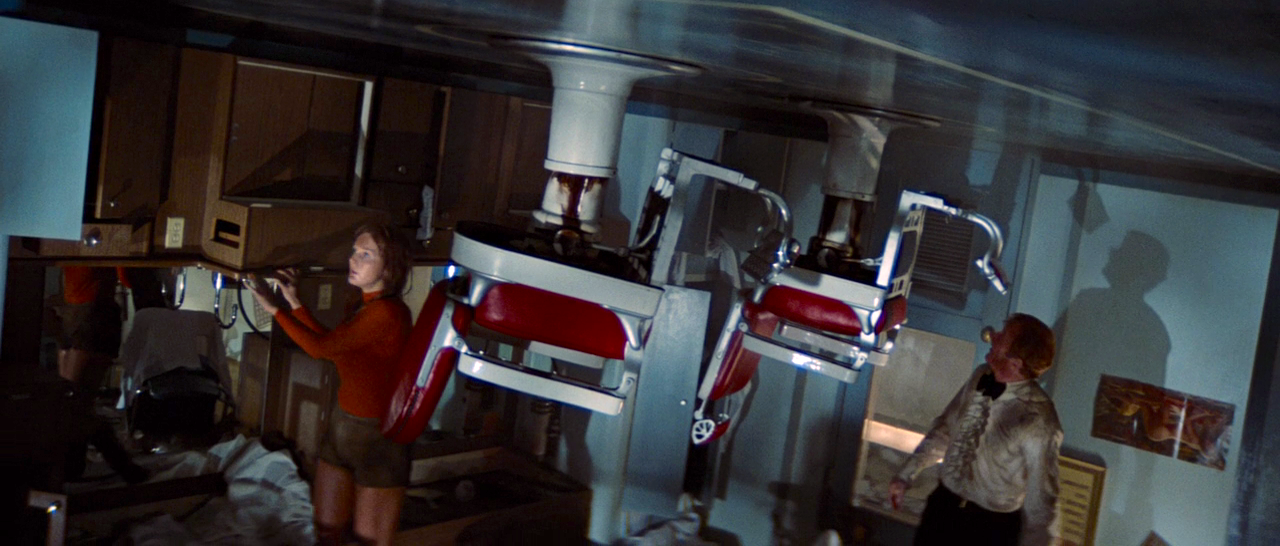

Then Neame and Bretton begin to play a bit more with the “upside down.” The first example is this barbershop, which Red Buttons suggests might inspire a new trend, trimming the hair of hanging customers.

There’s also a bathroom, which is remarkably clean under the circumstances.

All the while they’ve been searching for the engine room, the place with the thinnest hull. All of the dramatic tension on the way is built from the Reverend Scott’s confidence in this one route as the way of salvation. He has his believers and his skeptics, and it shifts as they go.

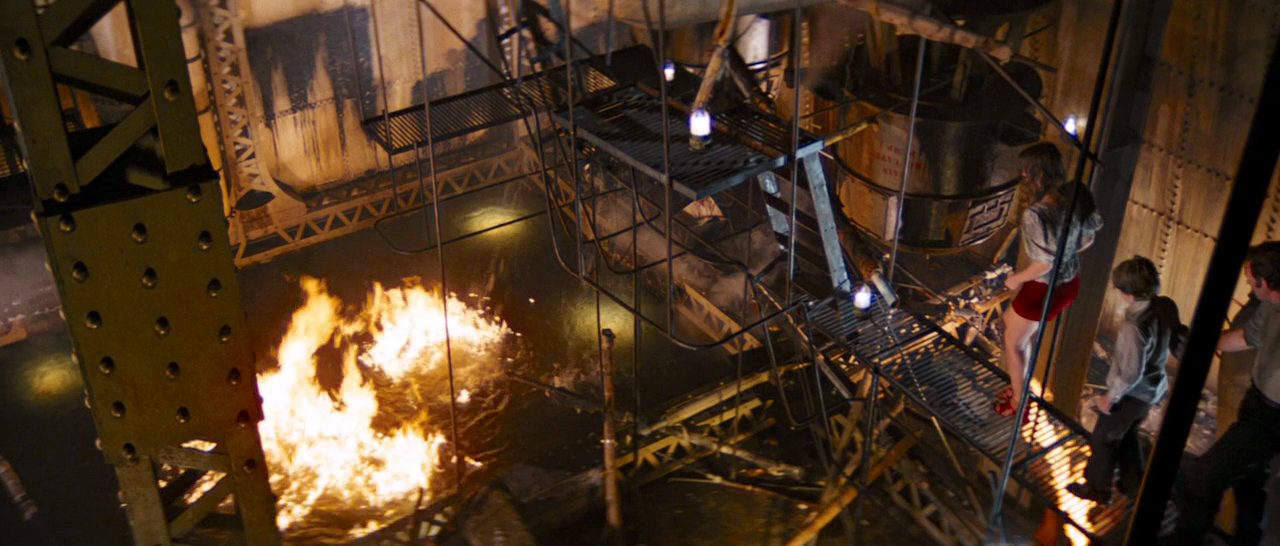

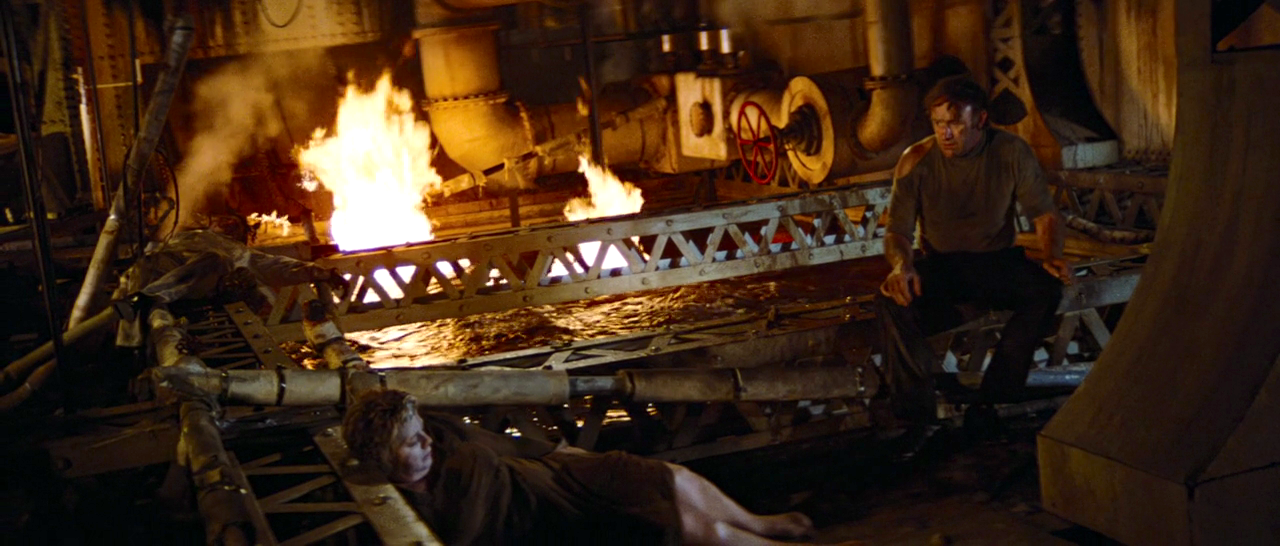

When they finally arrive, it is with a mix of relief and horror. The engine room looks like hell. This may be a bit out there, but it reminds me a little of Patrice Chereau’s production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, another grand and expensive 1970s allegory. The iron, steel and fire suggest a 20th century gone wrong, civilization leading to an industrialized death.

We’ve surpassed the momentarily surreal and the comically upside-down. Here is a space of real allegorical potential, a nightmare of oil and flame. The Reverend Scott and Belle are the first to arrive, swimming up through a sunken passageway. He nearly doesn’t make it, actually. Belle rescues him from a watery grave, pushing him through the water with the lungs that once won her an award from the Women’s Swimming Association. But then she promptly has a heart attack and dies, forever to rest in the engine room of the S.S. Poseidon.

Her sacrifice saves the Reverend, who will then go on to sacrifice himself in turn, leaping onto a steaming hot valve to get a door open. It’s the last obstacle, one more challenge before everyone else can go free. Before he plummets into the burning water below, he manages one last brimstone speech, shouting at his god in anger and frustration.

And so Ernest Borgnine, Red Buttons and the rest get to survive. It doesn’t seem fair, but then again perhaps it’s smart to give the death scenes to the good actors.

What does it all mean? Well I suppose one could read the Reverend Scott and Belle Rosen into a Christian Evangelical allegory of self-reliance and the sanctity of life, with the Holocaust as little more than a metaphor and the unseen Israeli grandson as an apocalyptic prop. Heaven knows this is a phenomenon that has only become more entrenched since 1972. But one could just as easily consider the whole movie to be Hollywood showmanship seasoned with thematic nonsense, like all the other blockbuster literary adaptations of the era.