Please welcome back former contributor Sean Donovan who returns to the fold...

With the 2005 Supporting Actress Smackdown quickly approaching TFE, let’s take a moment to think about a future Best Supporting Actress winner who was just then gathering her strength, summoning her powers of fierce alien glamour, and dipping a toe into Hollywood. 2005 was a pivotal year for Tilda Swinton in that it was her first engagement with big budget genre filmmaking. Tilda had found her way onto some Hollywood projects prior to this -- The Beach (2000) with Leonardo DiCaprio, Vanilla Sky (2001) with Tom Cruise, Jonze and Kaufman’s contemporary classic Adaptation (where she briefly shares the screen with Meryl Streep and my little gay heart explodes) -- but 2005 brought bombast, costuming, and blockbuster genre storytelling to her body of work...

In the beginning of the year the avant-garde actress graced DC Comics’ Constantine starring Keanu Reeves, and at the end of the year Disney’s lavish rendition of The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The renegade queer punk, introduced to arthouse audiences tearing up a wedding dress as Derek Jarman’s muse in The Last of England (1987), was now working in a context far closer to the flows of global entertainment capitalism, and left an indelible, singular stamp on Hollywood in the process.

Constantine is one of the odder would-be tentpoles to come out of DC Comics’ forays in film. Released in February 2005, the film uses the Hellblazer comics and their collage of spirituality and action for a dark, eccentric film that has more in common with pop-religious-supernatural entertainment like The Sixth Sense or Flatliners than it does Christopher Nolan’s Batman films. Keanu Reeves sulks as occult detective and exorciser John Constantine, tip-toeing across the line between the human and non-human worlds and policing the rowdy demons that aren’t where they belong. Reeves’ signature detached, strange persona (that might in some contexts be called ‘bad acting’) is on full display and lends a charm to the film as it struggles to cram mountains of backstory, mythology, and world-building into a limited narrative architecture. It’s all a bit overwhelming and rushed, characters played by the likes of Djimon Hounsou and Gavin Rossdale run in and out of the picture at a chaotic pace before we get a grasp on who they even are.

This overstuffed nature perhaps discouraged plans for a sequel, though Constantine seems fully due a resurgence of interest today. With Keanu’s new status as a lovable internet boyfriend, leading lady Rachel Weisz still driving queer twitter crazy from The Favourite, and sidekick Shia LaBeouf in the post-Honey Boy reflective moment of his career, the Constantine gang have all found transformed contexts of relevance in 2020. Jump on Hulu and check it out! Constantine the character has found continued play in the CW’s Arrowverse, and also in animation, where writers have engaged with Constantine’s queer sexuality that was omitted from the 2005 film. Making a film for a comparably conservative America, Keanu Reeves’ brooding super detective wasn’t allowed to express sexual curiosity in other men. And where else would all that displaced queer energy go, moved from the center to the margins, but to the freaky androgynous alien in the supporting cast?

Tilda Swinton plays Gabriel, an angel tasked with maintaining God’s standards on Earth. Appearing first in a men’s suit, a delicate swoop of red hair brushed to one side, she serves a kind of Oscar Wilde late-Victorian decadent energy, playful genderfuck theatrics as she’s seated in an antiquarian library. A destabilizing presence next to Keanu’s almost noir detective, Gabriel is a figure of order and discipline with a transgressive smirk and a wardrobe to die for. All of the queerness Constantine is denied in this film is placed onto Swinton’s androgynous Gabriel (and, to a lesser extent, Peter Stormare’s Lucifer). Tilda’s other appearances in the film, in roughly three big scenes, all include spectacles of gender-bending fashion. In a film that draws heavily from Christian mythology, Tilda Swinton’s Gabriel, supposedly God’s most loyal believer, embodies a kinky queer retort to the safe expression granted Christianity in the movies.

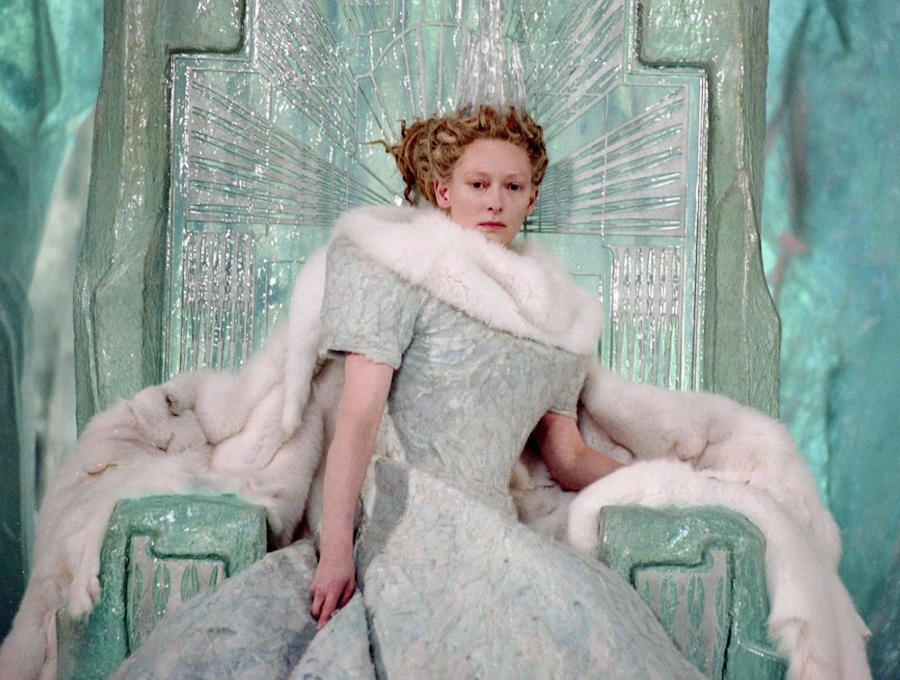

Later in 2005, Swinton would appear in another major Hollywood blockbuster that draws from Christian faith and tradition, this time as an iconic literary villain. In The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, Swinton plays the titular Witch as a grand treacherous diva with calculating strategy. Her striking appearance and severe features are deliberately used to emphasize her unusualness, and she plays this famous villain with regal iciness and an eerie, unsettling poise. Tilda strains against the family-friendly nature of the film at times- you can feel her discomfort when anything resembling the film’s disneyfied ‘comic relief’ comes close to her- but Narnia mostly provides a killer opportunity to watch Swinton model an array of truly stunning white gowns and coats (costumes by Isis Mussenden) with a pointed frozen mane of hair accentuating a powerful silhouette. It’s little wonder Edmund, the selfish and gloomy loner of the central kid hero quartet, should wander off like many queer young boys before him to follow the allure of a powerful diva in all her glory, rather than the stifling constraints of a biological family.

Of the two films Constantine has aged far better, contrary to mainstream critical opinions in 2005. Both films use heavy amounts of CGI, but Narnia’s attempt at ‘realistic’ CGI was doomed to look obsolete far more quickly than Constantine’s more expressionistic imagery. Constantine stands out as weird and defiantly singular, while Narnia bears the hallmarks of safe corporate filmmaking, carefully constructed at every phase of production towards commercial success. Tilda Swinton’s radical energy-burst defines small sections of both films, thoroughly enhancing them. Her magnetic presence and dazzling strangeness brought her avant-garde energy to unexpected venues in 2005. Just two years later she would win the Oscar for Michael Clayton, and eventually explore mainstream Hollywood franchises again with Doctor Strange and the MCU in 2016. For an actress who has often described her career as that of a ‘studio spy’ in Hollywood, 2005 can be seen as a decisive victory in her undercover espionage.