By Glenn Dunks

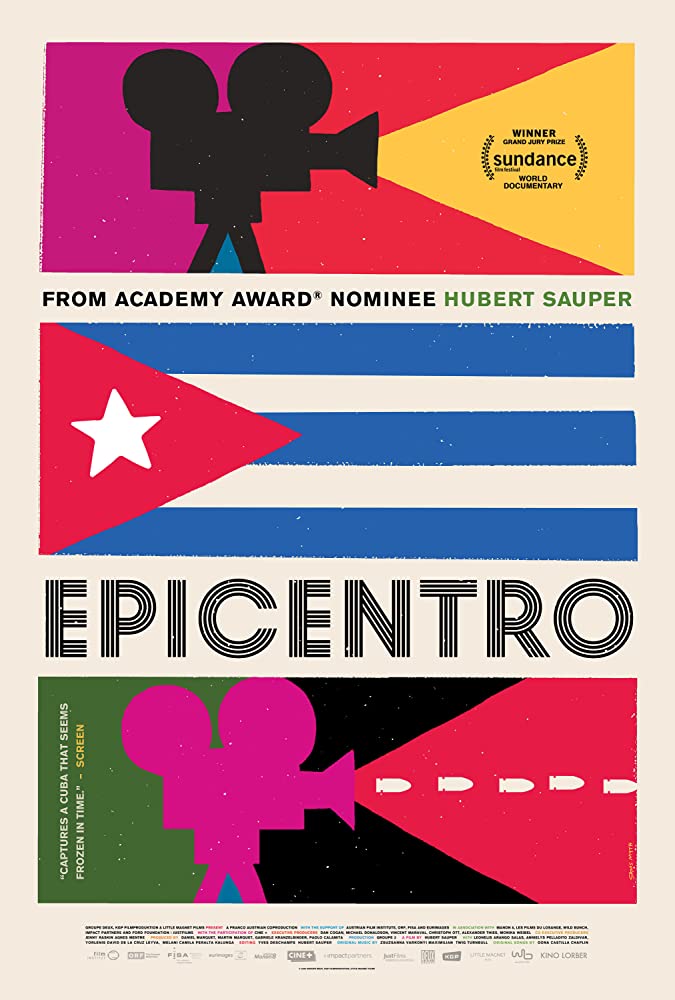

White faces invading Cuba is one of reoccurring images in Hubert Sauper’s Epicentro. And this includes the director himself. It is surely not lost on him that in examining the country’s place as “the epicentre of the three dystopian chapters of history” he at least somewhat places himself among the throngs of white, stickybeak tourists who get their ethnic cultural kicks by swarming barbershops to photograph young black boys getting haircuts before retreating to their glamorous five-star hotels.

White faces invading Cuba is one of reoccurring images in Hubert Sauper’s Epicentro. And this includes the director himself. It is surely not lost on him that in examining the country’s place as “the epicentre of the three dystopian chapters of history” he at least somewhat places himself among the throngs of white, stickybeak tourists who get their ethnic cultural kicks by swarming barbershops to photograph young black boys getting haircuts before retreating to their glamorous five-star hotels.

But this is what the Austrian filmmaker does, embedding himself within a place that has become a wrestling point of contention for lands beyond its borders...

And if his latest, only his fourth feature as director, lacks some of the propulsive drive of his last—the extraordinary We Come as Friends (one of the best of the decade), which found South Sudan in the grips of a contemporary colonial takeover— it still, nonetheless, finds its director digging his own unique path. He explores the devastating effects of slavery, colonization and the globalisation of power with an empathetic eye to the victims found in their wake who nonetheless see their homeland as utopia.

Beginning with opening narration that spans grand swathes of time and space in mere moments, Sauper then uses the history of film as a place-setter for contemporary Cuba. He takes us to 1898 when the modern Cuba was born out of the destruction of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor. Just in time for filmmakers to manipulate for the sake of patriotic nationalism (recreations labelled documentary were just literal smoke and mirrors), footage sent around the United States spurred the country into action to overthrow Spain as the empirical 'owner' of Cuba. He smartly uses this movie footage and more to highlight the nature of propaganda to a crowd of young children who learn very early about how storytelling tools shape our understanding of the world around us.

Many of these kids appear extremely advanced in their political understanding as a result and become the film’s most dominant figures. For as much as they speak eloquently about imperialism and the 1901 Platt Amendment, they also like to dance, swim and do photoshoots for their friends. It’s easy to see why the director was drawn to them.

There are others that the camera follows, but like his other films, Epicentro has a loose attitude towards shooting and cutting. Some of the footage is often roughly photographed digital where even the camera light flickers off and on throughout a scene. In another, he drifts away from a night-time serenade to watch the waves crash against the Malecón (one of America's earliest additions to the city in 1901) and then upwards still to the moon as it emerges out from under a midnight cloud. His themes of Cuba as paradise often emerge out of these sorts of extended sequences with Cuban nationals and music and love.

Meanwhile vignettes here and there highlight the fetishization by European tourists to the country’s plethora of restored classic vehicles before they shuffle off to their luxury hotel districts that are ghostly in their vast gaudy emptiness and which do more to highlight the poverty of locals than their living conditions do by themselves. When the kids see a silver-plated pen worth 600 times their mother’s daily wages (that would be $4), it becomes too hard to fathom. For some reason, Charlie Chaplin’s granddaughter, Oona, even shows up at one point.

All of this does mean that film can occasionally feel adrift. And there are indeed moments that don’t necessarily coalesce with the wider narrative. Those moments still offer off-the-beaten-track observations about Cuba that would likely go otherwise ignored. But then again, perhaps that’s intentional as Cuba itself is a bit like that. Disconnected from its military occupiers that has meant streets are now riddled with potholes, buildings stand seemingly on the verge of collapse, and water services are routinely turned off.

It asks questions like, “why is America always at war” that seem foolish to even attempt to answer. It quotes Mark Twain, “It is easier to fool people than convince people they have been fooled”, which certainly is pointed in its contemporary resetting. But ultimately it always comes back to storytelling and how the people of Cuba use it understand their own history—those three dystopian chapters of history—and to make sense of the world around them. For Sauper’s subjects the truth sits underneath the white tourists and the American propaganda and the expensive hotel rooms. And in a very roundabout way, the director does seem to find it, too.

Release: Currently playing in virtual theatres through the Kino Marquee platform.

Oscar chances: Sauper is a previous nominee for Darwin’s Nightmare, and We Come as Friends made the 15-wide shortlist. I think this one’s scrappier elements and a more expansive field jockeying for attention may mean it doesn’t reach that far into the season this time. Still, he clearly has fans within the branch. Plus they've been opening up in unpredictable ways so you can’t dismiss the possibility.