With Pieces of a Woman having premiered on Netflix, Vanessa Kirby becomes one of the big contenders in this year's Best Actress race. She previously won the Volpi Cup, joining a selection of other actresses who managed to turn a win at Venice into genuine Oscar buzz. However, not every Volpi champion is as lucky as to get a nomination. In 1993, Juliette Binoche managed to earn the Cup for her studies of loss in the first part of Krzysztof Kieslowski's trilogy about Europe and the French Revolutionary ideals. Still, when Oscar nomination morning arrived, Binoche's searing work in Three Colors: Blue was not found amid AMPAS' choices…

Grief is a complicated unseemly animal. To capture its true form is a challenge many artists have tried and almost as many have failed. The beast runs and hides, its body as unsolid as smoke, slipping through our fingers the very moment one starts to get a grasp. It's aided, in this perpetual evasion, by cultural and societal expectations of what grief should look like. Facing loss, to not cry can be as criminal as crying too much. Being acerbic is understandable, but only up to a point. Being listless and numb is a privilege we only give some people. The parameters are strict, inhuman, and as byzantine as any convention.

If we peruse film history, we can easily see many of those expectations in action. Notice the pressure for grief to be beautiful, a martyr's teary-eyed reaction to loss, limpidly emotional but not to the point it might become ever so slightly repugnant. When the saintly sorrow isn't the chosen path, there's always the opposed approach. It manifests in many stories about violent people, grief shedding propriety, assuming a new form that surpasses common hideousness to become more monstrous, more openly violent.

A tinkling simper or a bloodthirsty roar, a pretty implosion or a terrible explosion, these are the main modes in which mainstream cinema tends to portray the ever-changing face of grief. However, in both extremes, one hears untruth, a whisper of falsity, a song of manipulation. I don't mean to shame the common binaries of dramatized grief. Great works of art have blossomed from its fertile grounds, but one can't help but want more. The sad truth about this human reality is that it's often a mess, a complex web of contradictions that's ugly in unspectacular fashion, neither glamorous nor demonic.

It festers in the soul. It can freeze it cold, take it to boil, infect and sometimes even heal. Grief's a hydra-like beast. Cut off one head, and two more will spring forth, ready to bite you, kiss you, taste you, throw up on you. Perhaps because none of us wants to feel it though we're all condemned to do so, there's a collective effort to avoid its actuality and lose ourselves amidst vacuous idealizations. Whatever the reason, all this gibberish concludes that honest representations of grief are rare and to materialize them takes both a lot of craft, discipline, and courage, a willingness to repel, to shock, to scandalize, and confuse.

The glorious pair of Binoche and Kieslowski has all those qualities in spades, and their Blue is perhaps my favorite representation of grief ever put to film. What's more interesting is that, putatively, this isn't even an exploration of loss, but a celebration of liberty, of freedom. Only those things manifest themselves by way of tragedy, making us question the essential value of being free if the path to such deliverance is full of blood, small coffins, and mournful requiems. It all begins with a bang, a car crashing into a tree, smoke erupting from the wreck as a kid's ball bounces away. Death is the starting point.

Julie is the wife of a famous composer, and we meet her on a hospital bed, as she discovers she's the sole survivor of the accident that claimed the lives of her husband and little daughter. She despairs, though Kieslowski doesn't let us spend too much time in the instant of shock. Immediately after, Julie tries to commit suicide but is too scared to die, what remains of a survival instinct's keeping her tethered to life even as her heart may long for annihilation. Nonetheless, it's through destruction that she finds a new way of confronting her earthly existence. More specifically, she kills her old life by getting rid of its material signifiers, property and objects. All of it except a blue chandelier, the color she most associates with her family's fate.

Whatever wisps of plot exist in the film concern the composition of a hymn for the unification of Europe, a musical celebration of the fall of the Soviet Union and the start of a new era for the Old World. The piece was to be written by the dead man but is instead brought to life by our protagonist. Like Julie, the Europe of Blue faces a rebirth forged in the fires of bereavement. However, one shouldn't reduce the character or her film to symbolic puzzles. Julie finds her freedom in tandem with the continent, it's true. Nonetheless, hers is a personal story that's always played at the scale of people, not ideas.

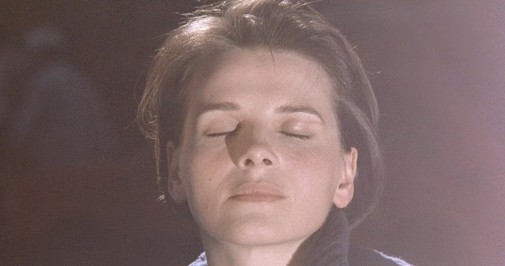

In some ways, Blue's a blunt film, one that announces its intentions in brusque directness while simultaneously allowing them to breathe. It's in those breaths that the spiritual power of the picture resides, that the actors' performances achieve greatness. Binoche is interpreting someone trying to build herself up from absolute despondence and doing so through negative actions. Not only is she getting rid of her old life, but she's also trying to erase her emotions. Some actors would perform the hell out of such bottled-up pain, but Binoche chooses to project this state of being by following along with her character. Like Julie, she attempts to erase any affectation, any inkling of personhood.

It looks, superficially, as an act of uncaring mourning, a performance of blank stares and little else. Try to look deeper. Investigate the pauses when Julie is looking into the azure shine of the chandelier, the instances she thinks nobody's watching. Then you'll see the crack in the façade, the effort by which this blank canvas avoids being painted on. Binoche isn't here to explain to us who Julie is or what she's going through. The actress is here to show the character living in the universe of the film. It's up to us if we want to make the effort to meet her where she's at or not. It's a prickly thing, uncomfortable to observe and singularly detached, a vision of grief as something that's intrinsically unknowable to those that stand outside of it.

Such insular feats of acting are hard to create and painful to appreciate. At a certain point, when staring into the void, the void stares back, and its eyes are our own. To get Julie is to see in her the reflection of our complicated humanity, the ugliness we carry inside, the sharpness, the despair. Re-watching Blue in the aftermath of my recent dealings with loss, I was keenly aware of the anger that lives inside Binoche's Julie. If you let her be alone for too long, you'll catch a glimpse of inchoate fury, a sudden self-mortification, the belligerent tension of a composer who wants to be deaf but keeps hearing the ghost of a future symphony. The anger of a woman who wants to feel nothing but keeps feeling.

Critics have described Blue as an anti-tragedy in the same way that White is an anti-comedy and Red an anti-romance. While I'm not too fond of this strict description of the trilogy, Blue and Binoche's Julie certainly feel as if they're deliberately trying to drain the tragedy out of a tragic premise. Out of death comes a new life, a new beginning born from an end. As Julie ends the film rejoining the world of the living, of the feeling, she has scraped herself clean in the purification waters of sorrow and came out necessarily changed. There's hope that those changes are for the better. The bloom of generosity to a hated adulterer suggests that, at the very least. Still, even when Julie's story nears a conclusion, Binoche chooses ambivalence. Grief is a mystery to the last second of Blue, and its leading lady valiantly keeps it that way.

Oscar-wise, Juliette Binoche did get further than many might suppose considering the arthouse nature of Kieslowski's odd hymn to liberty. The movie itself was nominated for three Golden Globes, including Best Actress in a Drama. In contrast, eventual Oscar nominee Debra Winger was ignored by the HFPA for her work in Shadowlands. Along with Winger, the rest of AMPAS' selected five were Angela Bassett in What's Love Got to Do with It, Stockard Channing in Six Degrees of Separation, Emma Thompson in The Remains of the Day, and the victorious Holly Hunter in The Piano.

Kieslowski's Three Colors trilogy is available to stream on the Criterion Channel and HBO Max.