"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

There’s an image from The Elephant Man I can’t get out of my head.

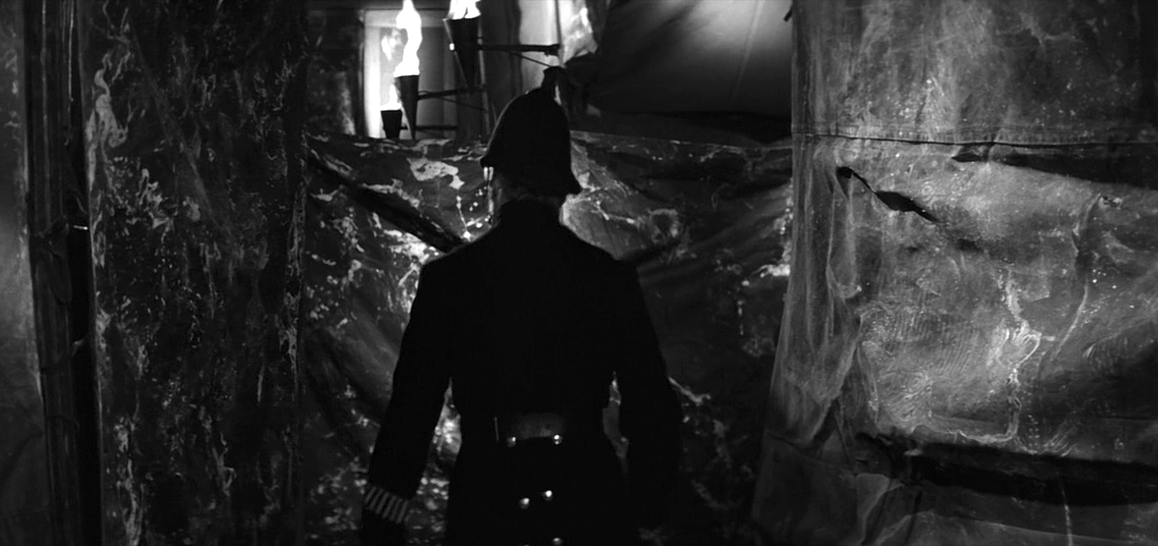

Well, there are a few. David Lynch and Freddie Francis didn’t exactly slouch here. But there’s one moment, quite early on, that struck me with its oddness. Dr. Treves (Anthony Hopkins) has snuck into the legally-tenuous circus of Mr. Bytes (Freddie Jones), just as the police are about to shut him down. The deeper one ventures, the strange the surroundings look. Here we see a cop navigating this temporary labyrinth of light and shadow...

What are the walls made of, exactly? It appears to be some sort of thick canvas material, perhaps used to slightly muffle the shrieks of wonder from the various exhibitions. Beyond their practical purpose, they’re also decorative - they must be, someone has tossed paint at them. There’s no discernable pattern, though. It’s practically Abstract Expressionism.

The physical material of the film’s sets is rarely so assertive. The Oscar-nominated production design begins with a bang, so to speak, and retreats to (relative) subtlety after. But the tone set by this subterranean episode never really goes away. The team of production designer Stuart Craig, art director Robert Cartwright and set decorator Hugh Scaife engineered a persistent visual refrain of stifling interiors and industrial alienation - even within the narrative’s most nominally peaceful spaces.

The theme of mechanical violence, in particular, is crucial. Lynch follows Dr. Treves from the freak show directly into surgery. “We’re seeing a lot more of these machine accidents,” he observes. The tools at his surgical table, some of which seem entirely prehistoric to the contemporary eye, suggest that Victorian medicine is struggling to keep up with the constant advance of industrial violence.

He soon returns to Bytes to purchase a private viewing of his “Elephant Man.” Upon meeting Joseph (or John) Merrick (John Hurt), the doctor will resolve to improve his situation, eventually establishing him within the London Hospital as a permanent home.

First, though, he has to walk there. Along the way he passes the hustle and bustle of the mechanizing meat industry, a wall of carcasses waiting for transport from the slaughterhouse to the butcher.

This visual theme of industrial shock and alienation will recur throughout the film. It’s almost as if the 19th century has turned all of London into a factory, replacing its air with soot and its sunlight with shadow. The decision to film in black & white certainly helps.

It’s a city somehow devoid of exterior spaces, a metropolis extrapolated from the bewildering subterranean circus where the film begins. Even at his return from a nightmarish abduction to the continent, Joseph is greeted by the ominous iron lattice-work of a grand terminal ceiling.

Suddenly a curious mob is chasing him into the depths of the station bathrooms - a nightmare of tile that feels like a damp tomb.

The thing is, his refuge in London Hospital isn’t all that visually different. The isolation ward, where Joseph eventually finds peace, is protected by a forbidding metal gate.

Lynch regularly introduces the apartments above with a shot of the tower’s innards, a muddle of beams with the vibe of a dark belfry.

The hospital barely gets more sunlight than the factoryscape outside. And as Nurse Mothershead (Wendy Hiller) points out, Joseph’s growing fame is replicating the circumstances of the freak show within the hospital. The only difference is that the gawkers who come to the Isolation Ward are much more posh.

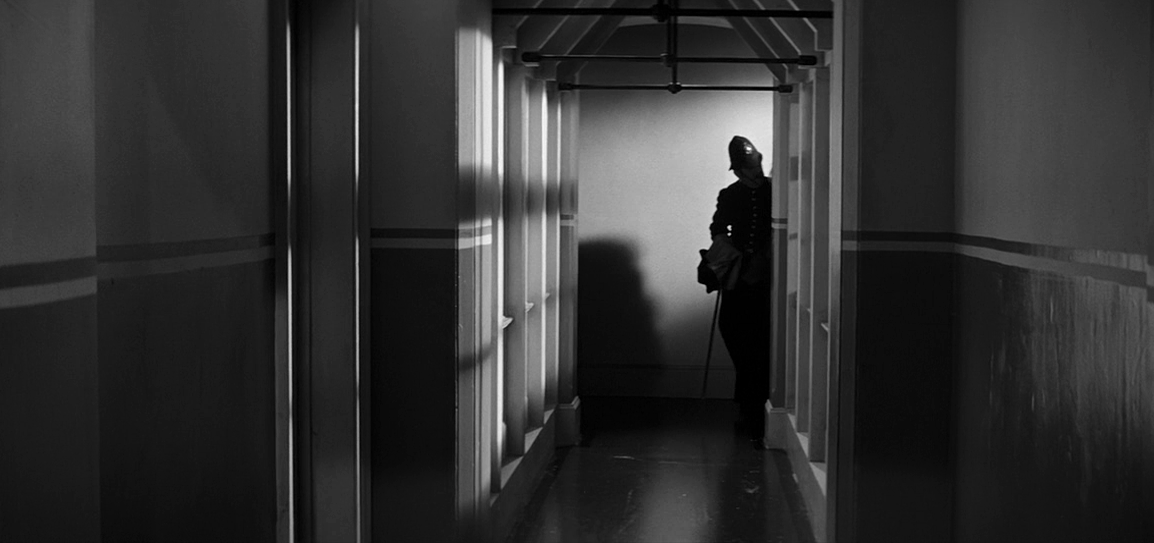

And the hospital’s halls are no more airy than those of the circus, either. The combined effect of the film’s design is brutal. The hospital becomes a factory, which becomes a circus, which becomes a prison - a frequently peaceful one, in this case, but with no less present a panopticon.

But for one detail. Joseph’s hand-made paper cathedral is a marvel, both of technique and of metaphor. Early in its construction, a nurse compliments him on the precision of the architectural details. Joseph replies that he can only work from what he’s able to see out his window, which isn’t much.

This little cathedral will be wrecked and rebuilt, then completed and signed in the film’s final sequence. What does it mean? Well plenty of things. But I’d like to make the case that its significance goes well beyond its architectural beauty, or its Christian symbolism.

Rather, by making a miniature model, Joseph turns the view from his window into something three-dimensional. He may never actually get the chance to ponder its full scope in person. But by making a complete replica of the cathedral’s exterior, he is able to remove himself from an interior. The cathedral, perhaps, makes him feel as if he is outside - in a city where no one is, at least not really. Perhaps his fantasy is to finally look through a window from the other side.