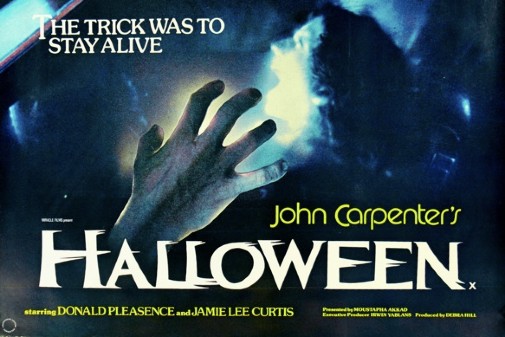

The release of Halloween Kills marks the twelfth feature in the franchise that originated with John Carpenter's classic slasher. It's been 43 years since it all started, but the story of Michael Myers keeps on engaging audiences. Unfortunately, four separate timelines have twisted it out of shape, making the monster into a druidic nightmare, a manifestation of murderous fate that chases after its own bloodline, a human psychopath, an inhuman abstraction. As for Jamie Lee Curtis' Laurie Strode, she went from the ultimate final girl to a scream queen offed off-screen to a traumatized woman and a violent avenger. Honestly, it's been a wild ride, and most of those sequels are misbegotten atrocities that deserve no attention. However, none of those sorry movies or their divergences from Carpenter's essential vision have retroactively worsened the first picture…

The original remains pristine, unmarred by subsequent mediocrities, a genre-defining masterpiece that deserves to be remembered with fondness, if not awe. Indeed, in the past few weeks, while anticipating the release of David Gordon Green's new entry into the Halloween franchise, I decided to watch all the movies in the series to confirm that idea. From 1981's Halloween II to 1995's The Curse of Michael Myers, I watched as the suburban fable of the first film became some monstrosity of inherited violence, byzantine beyond belief and increasingly cheap-looking. Then, the post-Scream era of horror brought upon Halloween H20 and the possibility for a decent ending to a mistreated saga. Of course, 2002's Resurrection spoiled it all.

Rob Zombie took the reins in the mid-aughts, remaking the first movie into a vicious artifact of nasty nostalgia that attempts to bring unsettling humanity to the figure of Michael Myers. The director's cut of his Halloween II is a Baroque piece of work, so deliriously unhinged it managed to win my affection. As for the newest flicks, the least said about them, the better, though they perpetuate Zombie's attempt at grounding the material in a world defined by pain. At the end of this journey, I re-watched the first Halloween, bringing it to a full circle, and the experience only served to highlight why the original is so effective. In the end, what surprised me the most was how at the heart of this cinematic beast, everything is built upon a foundation of simplicity, verging on horror minimalism.

Structurally, Halloween couldn't be more streamlined if indebted to the gialli of Italian cinema. There's a prologue defined by a stalking Steadicam flight, a POV from hell, and then a chilling crane shot that flattens the aftermath of murder into an iconic picture, a quasi-religious icon of childhood innocence turned into incomprehensible evil. What follows is a three-act structure that consists of roughly half an hour of daylight mood-setting, an encircling sense of evil and random killings on act two, and a final third marked by Laurie's nightmare as she tries to escape Michael. Many have read a puritanical punishment of teenaged sexuality into the killings of Laurie's promiscuous peers, Michael's preferred victims, but Carpenter disputed such claims years later.

While the narrative model served to solidify the slasher's sex-negative attitude for most of the 80s, what characterizes Laurie isn't so much her virtue but her loneliness. Jamie Lee Curtis plays Laurie like an adult in waiting for her teenage years to end, serious even when in the company of her randy girlfriends. It's not that she's anti-social. Instead, Carpenter and his actress define the female lead as a figure that exists as if floating by the suburban cosmos, aloof but always personable, alert, especially when on babysitter duty. In a genre often eager to reduce protagonists to archetypal caricatures, Laurie is complicated, appearing as someone whose inner-life exists but isn't fully perceptible to us, the audience. That is until the ending wrecks her. By then, even her complexity is smashed into primal emotion - pure panic.

Still, for most of the movie, she's full of private realities that are secret even from the camera. That sense of distance contributes to how real Laurie feels while also continuing the movie's minimalistic approach. If one were to point out what element best encompasses that artistic strategy, acting wouldn't be the first place to look. The music is probably the most evident proof and confirmation of that theory of horror minimalism. Carpenter, as ever, composed the movie's score, returning cyclically to a twinkling main theme that's eerie because of how infantile it sounds. One could imagine a kid learning how to play piano repeating those same notes over and over again, but the use of synth evokes an otherworldly quality.

The ditty becomes creepy, impossibly so, and part of the effectiveness stems from the rigidity of its motifs. Dean Cundey's cinematography and the editing of Charles Bornstein and Tommy Lee Wallace play a similar trick, repeating the same strategies with stoic severity. While never evoking an autumnal atmosphere, the film compensates for its lack of time and place specificity with excellent spatial awareness. Through Cundey's pristinely composed widescreen shots, one discovers a world of patient observation. We find out the suburban homes, the streets of Haddonfield, through a prism of cold cruelty. Chromatically, this manifests in some glacial blues painting the night air. Rhythmically, it lives in the long takes, the silence stretched until it becomes unbearable. Suspense emerges from inaction, not the spikes of carnage.

Transcending Curtis' performance and the complimentary lunacy of Donald Pleasance's Dr. Loomis, going beyond the formalistic coldness and the structural rigidity, one arrives at Michael himself and the story he unravels through his killings. Carpenter's greatest genius was his understanding of simplicity concerning fear. Understanding the boogeyman would deny the elemental powers that make it terrifying. Unknowability is scary. It's the deep shadows that gloom ominously where two eyes should be, the plastic mask that conceals expression, reducing the murder to only a facsimile of personhood. In other words, the key to making Michael Myers work is to make him so distant as to be incomprehensible, both a physical, psychological, and narrative level.

To this day, Carpenter seems like the only director to understand that, and even that knowledge abandoned him when writing Halloween II and its sordid twists. The original Michael stalks because he is fate, he is death, he is the shadow that smothers the light. He is a sketch deliberately unfinished, fragmented so as to be cipher-like. Perhaps because of that, his best cinematic apparition happens at the end of Halloween 1978, when, out of focus, the creature rises from apparent death. Why? It doesn't matter, and it should never be explained. Keeping things unburdened by narrative twistedness, the movie achieves the perfect alchemy of horror. It's minimalism highlighted by twisted flourishes here and there, just as the quietness of suburbia is broken by sudden savagery. It was the boogeyman all along, simple as that.

The original Halloween is streaming on Fubi, AMC+, Roku, Hoopla, Redbox, DirecTV, IndieFlix, Spectrum On Demand, and Shudder.