By Glenn Dunks

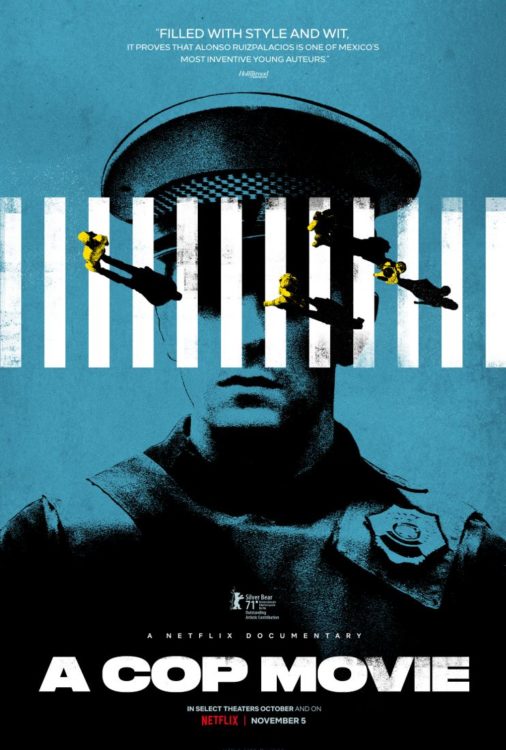

The release of Alonso Ruizpalacios’s A Cop Movie (Una película de policías) via Netflix was timed with a series hosted at New York’s The Paris Theatre. Named ‘New Directions in Documentary’, the series sought to highlight “the innovative films and filmmakers who have created new cinematic languages and forms by combining elements of fiction and documentary” (all Netflix titles, of course). Unsurprisingly, I have loved most of the films they played. Several of them (Strong Island, Shirkers, Bisbee ’17, Kate Plays Christine) made my own personal best of the decade list.

The release of Alonso Ruizpalacios’s A Cop Movie (Una película de policías) via Netflix was timed with a series hosted at New York’s The Paris Theatre. Named ‘New Directions in Documentary’, the series sought to highlight “the innovative films and filmmakers who have created new cinematic languages and forms by combining elements of fiction and documentary” (all Netflix titles, of course). Unsurprisingly, I have loved most of the films they played. Several of them (Strong Island, Shirkers, Bisbee ’17, Kate Plays Christine) made my own personal best of the decade list.

The series also recognised Robert Greene’s new film, Procession, which we will look at in the coming weeks. But Ruizpalacios’s feature—which directly taps into the series’ concept of playing with the concepts of artifice, performance, and the documentary filmmaking process—is an interesting inclusion. It’s the only non-American title for starters, from the director of Museo. It’s nice to see somebody recognise that innovation in doc filmmaking is happening everywhere.

The film follows two officers on the Mexican police force and is told through elaborate reconstructions. Ruizpalacios and editor Yibran Asuad don’t make it immediately clear what is real and what isn’t. Likewise, who is real and who isn’t. Although it is beautifully shot by first-time cinematographer Emiliano Villanueva, repeatedly bathed in the red and blue of a police car’s lights, there is obvious manipulation at play and it is often integrated in ways the heighten its story from the streets of Mexico City.

There is Teresa, a woman once eager to prove to her policeman father that she has what it takes to follow in his footsteps. There is also Montoya, a well-meaning larrakin type. The pair are collectively known as “the love patrol” after their burgeoning romance was discovered. Halfway through, however, the script is flipped and Ruizpalacios’s film changes drastically. The audience learns the truth (or, part of it) and from there A Cop Movie becomes more traditionally filmed and structured. It moves away from the inventively written and well-shot recreations to incorporating video diaries shot on mobile phone with investigative journalism and talking heads.

What this shift in filmmaking style is meant to say is where it gets quite murky. It’s clear that Ruizpalacios has thoughts on the police and the act of policing, as well what appears to have a genuine curiosity about the sheer mechanics of being a cop in Mexico. These are very similar ethical concerns to other documentaries from all corners of the world. That these concerns are universal is probably why he was wise to attempt something more structurally daring to confront it.

But as he follows Teresa and Montoya’s story and its inevitable swerve into corruption and greed, the filmmaking innovations appear to grow increasingly beyond the point. Or maybe it becomes a mask, for the more insidious ideas about policing that Ruizpalacios struggles to reconcile.

In a way, A Cop Movie highlights how extremely difficult it is to make a movie about the police that is critical of the system. It’s hard not to romanticize it in some way when filtered through a subject’s POV who, corrupt or not, sees their role in society as that of a great good. Even films about crooked cops often ultimately find themselves emphasizing redemption and the good apples (so to speak) who are just trying their best in a bad system. For example, as I watched A Cop Movie I also thought of Sidney Lumet’s Prince of the City about Robert Daley. I also thought of Peter Nicks’ The Force from 2017, which I felt did a better job of balancing our desire for police to be good with the reality for many in society that they simply are not.

Whether you believe the ACAB rhetoric or not, interrogating the police force is such a tricky space within which to navigate and I’m not entirely sure Ruizpalacios succeeds. Although it is interesting to watch him try. A Cop Movie will pair well for viewers with Luke Lorentzen’s Midnight Family from 2019 about the ambulance shortages in Mexico City, that’s for sure, though.

Alonso Ruizpalacios has said that “performing is an essential part of a police officer’s life.” That they must put on an act along with their uniform and display strength and skills they likely do not have. It is an arresting (no pun intended) thought that would typically be well-served by something as structurally playful as A Cop Movie. But by its end, I am unsure what the film really has to say about corruption in Mexico’s police and Mexico’s relationship with police. It’s not positive, of course, but the use of performers and non-traditional methods ultimately feels distracting from something bigger. Some cops are bad, others aren’t. Okay. But what about the system that allows for this in the first place?

Release: A Cop Story will have a brief theatrical run from today before streaming on Netflix from November the 5th.

Awards chances: The documentary branch haven’t been as kind to form-stretching titles as only one of the aforementioned inventive titles, Strong Island, was Oscar-nominated. I probably wouldn’t expect A Cop Movie to join it, but non-American titles, especially those with the backing of Netflix, probably have a better shot than most. It is also on Mexico’s radar as a Best International Film submission, but I would prefer Identifiable Features there.