Last year, when exploring the wonders of horror costuming, I sang the praises of Eiko Ishioka's Oscar-winning Dracula designs, a heady mixture of Nipponic fantasy and Victorian fashion. While that's a cinematic wardrobe for the ages, it's fair to say Eiko's most crucial big-screen collaboration wasn't with Francis Ford Coppola. Instead, that would be her decades-long teaming with Tarsem Singh. Indeed, the Japanese artist's work with the Indian director became so intrinsic to his filmography that she could be considered a co-author of those movies. Her vision is vital to their final form. So much so that, after her death, Tarsem's cinema lost some of its spark. He's yet to return to the visual heights he had achieved with Eiko. Of the four features they did together, The Cell's the only adventure in the horror genre, a nightmarish plunge into a serial killer's psyche…

Like Hellraiser, The Cell represents a collaborative effort of costume design more significantly than the typical film project. Two credited designers, Eiko Ishioka and April Napier, match the two modes of visual storytelling and realities the movie moves within. Based on their careers alone, it feels safe to assume that Eiko took on the trippy surrealism while Napier created the grounded reality from which those other dreams blossom. This is a bifurcated story, of course, one that starts in a sci-fi clinical environment where doctors have devised a technology that allows one to enter the unconscious mind of another. Their research focuses on comatose children whose minds are trapped inside their bodies. By the end, though, such wonders will be employed for another purpose altogether.

At the same time child psychologist Catherine Deane (Jennifer Lopez) tries to save her patients, a serial killer terrorizes some anonymous American location. Carl Rudolph Stargher (Vincent D'Onofrio) likes to kidnap women and play with their bodies, enclosing them in glass cells that slowly fill with water. He watches them drown and uses their death videos for sexual gratification, their suffering an aphrodisiac. Still, when the FBI finds him, at long last, he has succumbed to the same schizophrenic infection that victimized Catherine's case study. Simultaneously, Carl's latest catch is already inside a drowning tank in an unknown location. So the clock's ticking, and only the murderer's mind holds the key to saving an innocent life. You can guess what happens next.

Before exploring the demented excess of Eiko's designs, one shouldn't ignore the nuanced craft of Napier's work. Establishing the context for the dreamscape is important, clueing us to the neuroses that later manifest inside the unreal world. There's also an imperative of contrast, strict dichotomies separating one dimension from another. To better achieve these visual relationships, Napier clothes the characters in collections of curated drabness, matching them to their surroundings through paroxysms of brown, grey, beige, and black. It's eerie how the real world feels like it's had its quirks sanded off, bleached clean like Carl's doll-women. Furthermore, Catherine's everyday life holds the key to understanding her dream self. Hints in her home indicate references that later explode into mental costumes. There's plenty of religious imagery and sci-fi psychedelia on the TV while she wears looks of unassuming conventional femininity.

Enough about the mundane existence. Let's look at The Cell's maddening lunacy. For starters, it's essential to establish repeated motifs, chief among them the idea of suspension. It manifests in multiple iterations throughout the picture, bleeding out of Carl's mind into the world at large. There's the fetishistic suspension for which the killer has implanted piercings on his back. We also have the tanks that serve as his victims' watery graves. Logically, the surreal inner world of his mind is full of such images, like when Catherine falls upwards in a flurry of crimson and then floats, suspended in mid-air like a cloud of red ink in a glass of water. However, the suspension doesn't only surge forward from Carl's imagination. In cryptic foreshadowing, it's an essential part of Catherine's world, a way to help mind and flesh disconnect.

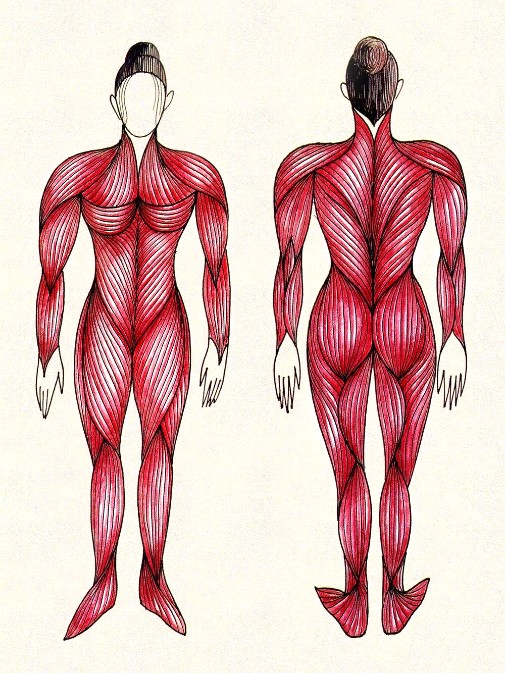

The therapeutic technology necessitates the suspension of bodies dressed in special rubber suits. Intersecting therapy and murder once more, they look like floating corpses, flayed alive with their heads covered to hide dying expressions, their death masks. The sinewy sculpt of the red suits further suggests both blood and musculature, an echo of Dracula's anatomical armor in the Coppola movie. This time, though, Eiko's sanguine obsessions are a tool to look at undiscovered technological futures rather than forgotten pasts. They forge a pathway through which Catherine accesses the nightmares inside Carl, starting with labyrinthic architecture that couldn't be more distant from the comatose children's storybook deserts.

Giger, Hurst, and Nerdrum were important artistic references for Tarsem. While Eiko didn't quote so directly, it's possible to denote the influence of fashion designers like Gautier, Mugler, and Miyake in the dream wardrobe. This is evident from the start when Catherine's voyage through the mind's maze leads her to a horrific museum. The gallery of ghouls presents women as caged animals, embodying Carl's twisted views of femininity, his idealized bodies. People are made into cruel archetypes within those hellish tableaux, collars, and metal fixtures strapping red and silver across their faces and necks. Even the naked bodies feel imprisoned, while the partially clothed ones serve to model bleached skin suits punctuated by kinky accessories, signs of submission, symbols of multifaceted violence.

We glimpse sex slaves and tortured victims, motherly saviors and fierce warriors – all ideas that Catherine will end up personifying, one way or the other, through more spectacular costumes. Notice that when Carl's subconscious takes her hostage, the psychologist becomes another woman in a scarlet collar and metallic face jewelry. In this garb, she's one more of the killer's prisoners, sexualized against her will and reduced to lifeless ornament. Only when the metal tendrils are taken away and the camera pushes close enough so that the plastic collar disappears does her will supersede Carl's influence. Framing and costume work together to visualize shifting power dynamics, eroticism charged with discomfort.

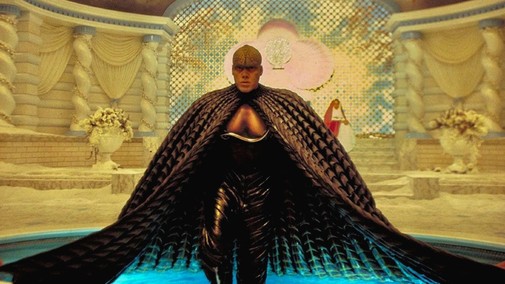

Curiously enough, Lopez wasn't a fan of the look and felt the collar, sculpted to replicate the actress' clavicle, was too tight. Eiko's response was withering – after all, the character is meant to be tortured. Tortured by the man into whose mind she's sinking. As the journey continues, the killer's psyche fragments in two. On the one hand, there's young Carl, a childish ghost of innocence lost. On the other, there's King Stargher, whose malevolence embodies psychopathy ran rampant, unbound and unraveling. While the young boy dresses in the realistic garb of memories – look at those 70s collars and prints – the demonic King is all jesting opulence. Initially, he's more tethered to a present version of Carl, back piercings continuing into a monumental purple cape, the color of royalty, and arms painted in the yellow hues of the gloves he wears to dismember cadavers.

However, as if illustrating our fall into the deeper recesses of the unconscious, the King becomes more abstract. In one moment, he's a papal monarch with bejeweled capes and a crown, ropes around the neck to mimic the intestines he's pulling from his victim's belly. In the next scene, the garment has evolved into an acrobatic jester costume, creepy for its animation and tainted joy. By the end. The abstraction has gone so far that King Stragher appears to be an animal, reptilian textures and leathery scales blurring the divisions between body and costume. It's disturbing, and yet, one can't look away from the unholy beauty of it all. If King Stargher's a devil, Catherine designs herself in the shape of an angel descended from heaven.

There's a Marian quality to Catherine's conception of herself as keeper of children, a messianic figure that walks the desert to free young souls from their mind's prison. Like D.H. Lawrence, she's a storm of white across the sandy sea. Only her garments evoke haute couture fairytales rather than Arabian garb. Her white dress is an intersection of nature and machine, angelic feathers and synthetic plastic textures over silky expanses, vaguely bridal and warrior-like. Later iterations of the same concept will see less armored propositions until, at long last, she becomes a Virgin Mary figure, literalizing the underlying metaphors and putting them forward without shame or subtlety. Still, one sees other bright colors cut through the total white in the set and costume. There’s the blue so associated with Catholic depictions of Mary and the red that foretells bloodshed.

The saddest twist happens as we understand that, to defeat King Stargher and save young Carl, Catherine must choose a path of annihilation rather than beatific forgiveness. The white shapelessness melts away to reveal a hard-shell bodice with anatomical details, all in black. It's a costume for killing, a deliberate mirroring of the King's dark reptile appearance. The heroine succumbs, deliberately stepping into the killer's violence in order to end the chaos and deliver a final mercy. In the end, though, when putting the young boy to rest, she returns to the Virgin outfit, saying goodbye with kindness rather than fury. Or maybe, the biggest horror of all is that, in her limited purview of humans, Catherine can only see herself as either total purity or pure evil, nothing in between. It's a tragedy of imagination told through costume design.

The Cell is streaming on Hoopla and Starz. You can also rent it on several platforms.