by Nick Taylor

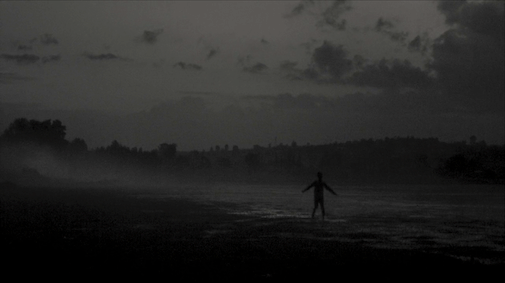

First thing’s first: Faya Dayi easily ranks as one of the most beautiful 2021 films I have seen. I don’t mean to equate its beauty with an automatic FYC for best cinematography, nor a backhanded comment on style over substance. In cahoots with the editing and sound design, the heavy, monochromatic images cloak Ethiopia in a hazy, dreamlike aura that’s foundational to the film’s tone and point of view, and unspeakably gorgeous to boot. I could've pulled a gallery's worth of screengrabs from the first five minutes alone. Producer/director Jessica Beshir also acts as her own cinematographer, and her ability to endow her images with such clarity and attention to movement, texture, and composition is a stunning achievement.

But is it fashion? Does the gorgeousness of the imagery actually serve the film, or is it too loaded down to carry its own weight? How much movie truly lies underneath all this black and silver? Well...

Faya Dayi takes place in the Ethiopian village of Harar, where Beshir grew up as a child. Her family fled the country when she was young, and in the time she was gone her village underwent a radical shift in which crops it produced. Originally renowned for their coffee plants, Harar now exclusively exports a stimulant plant called khat, which Ethiopian legend purports was prized by the Suli Imams as a way of connecting to eternity. The plant is now a cash crop sold across Ethiopia, and Harar’s economy is primarily (if not exclusively) based on harvesting khat, transporting it, and selling it to villages across the country. Faya Dayi is very much a showcase of how khat is harvested, and film’s style is meant to replicate the haze borne from being immersed in so much khat. But even more than that, Beshir’s camera is interested in weaving through the lives of the villagers who prepare it, depicting Harar as a town lost in the sauce of its endless khat supply.

Although the film has been classified as a documentary, the filmmaking gives it the feeling of a tone poem. Harar is more of a dreamscape than it ever is a physical location, one replete with older folks who long for the days of farming coffee and young people trying to handle khat-addicted relatives and hoping to leave Ethiopia altogether. Their testimonies are loosely scattered throughout the film, with a couple figures recurring through the film as they recount Harar’s history or debating getting passage to Egypt. I don’t know that Beshir gets away with how several scenes plainly read as restagings of earlier, off-camera conversations, but it fits Faya Dayi’s out-of-body tone better than a traditional documentary.

Still, the question remains: Is it fashion? Part of me suspects I might groove to Faya Dayi a bit better on rewatch simply by virtue of being acquainted with its peculiar style. Maybe it simply works best when the viewer is trapped in a theater. But I may also dive in again and emerge more frustrated with how Beshir’s style doesn’t really facilitate the sort of portraiture she’s aiming for. There isn’t much structure connecting one scene or testimony of Faya Dayi to the next, especially after the latest crop of khat has left Harar. I’d argue that folks who only appear for one or two scenes have the hardest time resonating, but even the people we return to throughout the film are too spread out for their stories to really land. The young man who wants to go to Egypt is present for a good number of scenes, but a specific plan to flee to Egypt that’s mentioned in his first scene doesn’t come up at any point until the very end of the film. Faya Dayi’s dreaminess has a hard time sustaining some of the more upsetting discussions people have about how their loved ones behave on khat. The heaviness of the cinematography ultimately makes the film as whole too impenetrable, even when it’s presenting a genuinely affecting story or striking image.

There’s also a problem with flow and pacing that, for my money, holds the film back even at its most promising points. Faya Dayi struggles completely with momentum, from the level of its overall structure down to individual edits, and I found it difficult to swing from so many jumps between a mood-focused montage to a one-on-one with someone we haven’t met before. It’s frankly surprising Beshir spends so much time reinforcing her dreamlike tone when it’s already so potent in even the most character- or information-focused passages. I expect if you’re in the film’s groove that its transitions and choices on what to focus on read as intuitive or surprising in a dream-logic sort of way, but it felt increasingly disjointed once it became clear that there wouldn’t be much to hold onto from one scene to the next except for the tone.

I admire a lot of Faya Dayi’s risks but spent a lot of my time with it thinking of Khalik Allah’s 2018 film Black Mother, an even more formally ingenious and narratively risky documentary that attempts to survey the past and present of a whole country, without striving for heterogeneity or being easy to sit with. That film gets away with telling about a hundred stories at once, all of which stand out on their own and still add up to a multifaceted presentation of Jamaica. Beshir could stand to let the many histories she presents breathe on their own terms. There is every chance you might get more out of this than I did. I might even get more of this on a second watch than I did now. But I mostly feel as though Faya Dayi has a lot of fascinating, worthwhile stories that its incredible lensing ultimately smothered a bit. The gains in mood and atmosphere richly convey a very real, very sad idea about Harar’s trajectory, but the inability to bring out the stories of the people living in the city’s fog prevents the film from really becoming something special.