By Glenn Dunks

It’s become somewhat predictable that a new Robert Greene will challenge an audience as much as it enthrals. He doesn’t exactly pick the most digestible of subject matter, but the way he comes at them is always so interesting and refreshingly unique that it becomes more than just a dour excursion into humanity’s darkest corners. While some may question his tactics, often interpolating traditional non-fiction form with performance and scripted drama, there is nonetheless a quality to his works that poke and prod at the most sensitive parts of a viewer’s brain.

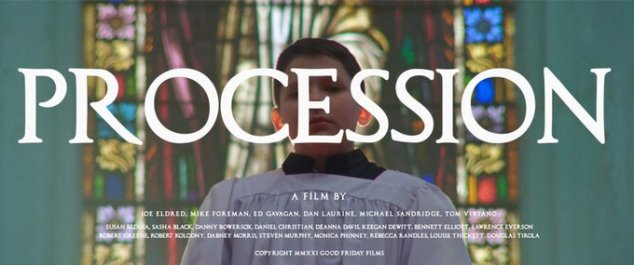

His latest, the Netflix-distributed Catholic Church abuse drama Procession is no different. More so, it’s the best documentary of the year.

Shot predominantly in Kansas City, the subjects of Procession are all clasped fists and fidgety fingers. They are six men who all suffered abuse at the hands of Catholic priests in their teenage years and whose efforts at justice have collectively been for very little. We learn throughout about the fate of their abusers and they have a right to be angry and betrayed. By its end, the effect of this experiment appears clear, although anybody who’s seen or read anything on the topic (or, heaven forbit, have experienced it themselves) will know it’s likely not that easy. Thankfully, I don’t think the film assumes it will be.

One of the strongest ideas of Procession, the very core of the film really, is that it isn’t Greene or anybody else taking back the power that the abusers have had over them all these decades. It is the men themselves. In its opening credits, Greene’s name isn’t even mentioned, rather it is “a three-year collaborative process between the filmmakers, a professional drama therapist and the survivors.” By asking these men to write, direct, star and even build sets for a mini film within the film seems like a stroke of dramatic genius. That it allows them to come together, damaged but willing to be each other's confidant on screen and off only makes it all the more powerful.

The experiment is to purge demons through film. Remarkably, what it reveals in these men is something akin to childlike imagination. Some kind of miracle all its own given these men had their childhoods torn away, tainted and likely didn’t get to experience to sort of youthful joy that they were meant to—particularly given they grew up in the Midwest where, so we’re often told, these sort of things aren’t supposed to happen. Of course, the glee some experience firstly at being able to creatively tell their story is replaced at some point by fear and dread upon revisiting the churches and the lake houses where their abuse happened to confront their experiences. In one man’s story, he evokes Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz with the role of showman going to a priest. Another man recreates the ‘independent’ review of his own case where he hurls a torrent of pent-up anger at actors and strangers. The revelations that come out are deeply personal, deeply effecting, and raw.

Subjects as auteur is not something too much discussed in documentary, but here it likely very much feels like it should be—even if the finished product bears many of the stylistic and storytelling trademarks of Greene himself (beyond the form, Procession looks great, and Greene’s own editing is yet again stellar).

There have been many films about this subject matter of the abused reckoning with their experience. Some of them great (documentary: Alex Gibney’s Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God; fiction: François Ozon’s By the Grace of God). Many are quite standard. When one of Greene’s subjects says he doesn’t want the project to be mere self-flagellating on camera, it’s actually kind of funny if you are at all familiar with his work. Like Kate Plays Christine and Bisbee ’17, Green has extracted some kind of catharsis out of this terrible pain in the form of this incredible film. It’s hard to imagine a documentary this year more effectively using art for the betterment of its subjects’ humanity.

Release: Streaming globally on Netflix.

Awards chances: Robert Greene has never made the Oscar shortlist, but I think this year could be the one. Its Netflix release will surely help, but his reputation has only grown and grown over the years. Unlike his other films that use a similar device, Procession does it the best while still never hiding its documentary roots, which could be the deal-maker for the doc branch.