Despite starring in two Best Picture winners and many other movies blessed by plentiful love from AMPAS, Christopher Plummer always struggled to be recognized by the Academy. While the actor earned a lot of golden accolades and nominations for his TV work, including two Emmys, his cinematic efforts rarely caught the attention of awards-giving bodies. It was only in the twilight of his career that such fate changed but that doesn't mean he wasn't deserving before. For example, in 1965, the year of The Sound of Music, I'd have happily nominated him both for his stern star turn as Captain von Trapp and for the malicious sensuality he brings to Inside Daisy Clover.

Still, the closest he ever came to an Oscar nomination pre-2009 was for Michael Mann's The Insider...

That 1999 Best Picture nominee is a near-perfect movie, a fictionalized retelling of a scandal that rocked CBS and the tobacco industry in the mid-1990s. It happened when a former big tobacco executive turned whistleblower, Jeffrey Wigand, told an investigative reporter from 60 Minutes, Lowell Bergman, about lies the industry had been telling the public about its knowledge on the addictive qualities of their product. When it came time to bring the information to light, the CBS legal team insisted on a heavily redacted version of the story instead of the original interview between Wigand and Mike Wallace.

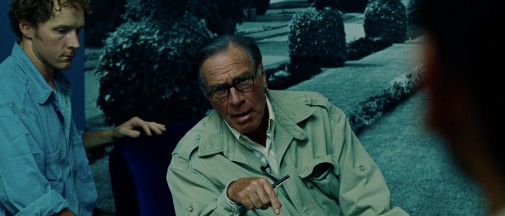

Plummer plays the famed interviewer, a supporting role in comparison to Al Pacino's Bergman and Russell Crowe's Oscar-nominated work as Jeff Wigand. In many ways, the arrival of the actor is presaged by grand anticipation. Not only is he the most famous real-life character being represented but Plummer himself brings with him an aura of wizened stardom. Fittingly, we hear about Mike Wallace before we see the man, his first scene being the closest thing this hardened procedural has to a star entrance. In an Iran-set prologue, we see Wallace control a room as his strong will cajoles those around him, including the security team of the sheik he's interviewing. In no time, we've grown to respect Plummer's Wallace, cowed by his sense of unshakeable authority.

There's an impertinent pride to Plummer's Mike Wallace, the sense of power of a man used to getting his way, even when around some of the most dangerous people in the world. He might explode one moment, and quietly demand vassalage to his authority the next. It's an intelligent variation of professional imperiousness, one that exudes majesty with ease. It seems to come organically to him, no forceful effort visible. In that sense, Plummer embodies the role, smoothing the separation between actor and character until there's little to no friction between the two. Like The Insider itself, the portrait works more as a myth than as a docudrama and it's all the better for it.

This isn't the Mike Wallace of the history books, but the man of legend, a titan who bent the knee when things got tough, disappointing those for whom he had been a mentor, a figure of inspiration and aspiration. In the actor's own words, he wasn't doing an impersonation of Mike Wallace, rather a loose impression of the man that focused on ideas of professional pride and crumbling integrity. He does look like him but other elements reveal the distaste for carbon copy. The voice, apart from some precise speech cadences taken from Wallace's on-air persona, is all Plummer's usual register. He's an actor who molds a role to his specificities as a performer but does it with intelligence and attention to detail. He doesn't disappear into Wallace, rather he makes the script's vision his own.

At the same time, it feels distinct from Plummer's other performances. The performance comes off as unique, singular, transformative even. I wouldn't blame anyone who said the actor is unrecognizable as Mike Wallace, even as I disagree with the assessment. There's a healthy edge of theatricality to Plummer's powerful presence. It's a factor in all of his screen work, but in The Insider, it manifests in a quiet magnetism that brilliantly meshes with Mann's cinematic style. Between the handheld nervousness of the shots and the precise, often feverish, editing, Wallace holds the eye like a portentous monument, his expression defining the scene's mood. It's a magnanimous, majestic thing to observe like a great sight of natural wonder, a waterfall, or a great mountain.

To understand how this performance works, though, we must understand how the film works too. The Insider is constructed in two acts, bookended by a scene-setting prologue and a mournful epilogue. Plummer's contribution to the first portion of the flick is as a delineator of tone, often letting his strong presence take over as he observes from the background. The second act sees that monument crumble once the camera and the audience's attention become laser-focused on Wallace's choices, his caving in to pressure from the higher-ups. It's a smart bit of structuring, both in terms of script and performance.

It allows Plummer to act through a harsh character arc without calling attention to the changes, letting things naturally reach their fraught conclusions. The hints are there from the beginning, like when his joyous charm at a dinner melts into patrician indignation when faced with his interviewee's stress. We can also see it in his dealing with the lawyers from CBS, how he puts on his interview face in conversation with them. Because of all that, the shocking moment when Wallace agrees with the corporate higher-ups feels inevitable. Plummer plays it with no bolster either, just a muted, stoic, almost shameful agreement. Of course, the true acting showcase starts when things go wrong for Wallace, from the cutting of a pre-recorded statement to the New York Times article exposing his agreement with corporate censorship.

His scene in Lowell Bergman's hotel room in the aftermath of betrayal is amazing. Disappointment and prideful resentment wear him down, the TV star looking like a king who's been deceived by his closest minister. As he explains his perspective, why he caved to pressure, neither Plummer nor Wallace asks for sympathy, but the articulation of complicated emotions is impactful nonetheless. As he sees the end of life near, this old legend worries about his legacy, about the final chapter in the story of his life. Sitting in a nondescript hotel chair in a sad little room, he's a man talking with the weight of mortality bearing down on him. Someone who realizes they might have jeopardized the only thing he cared about as well as lost a friend.

He tries to explain himself, but one also feels the tinge of nervousness, the disquiet of a trained orator trying to talk himself into a lie. The next day, he's acting as if nothing happened as if he knew he was wrong all along. The patriarchal soothsaying of a king is back. It's impressive how quickly he switches modes, becoming superhuman instead of that frightened individual with a hurt pride in the hotel room. Still, the crime is done and we must all pay the price. The real Wallace may have spoken against the film, but Plummer allows him to keep his dignity to the end. As Bergman turns his back on the mentor figure during the men's final scene, Plummer says goodbye to his audience with an enigmatic half-smile. It's a perfect note to end, a reticence that leaves us wanting more even as we feel like we know exactly who this version of Mike Wallace is.

In the awards season of 1999/2000, Christopher Plummer got quite a lot of critics' honors. He won the prizes from BSFC, LAFCA, and the NSFC, while he was nominated by the CFCA, LVFCS, NYFCC, OFTA, OFCS, SDFCS as well as the Satellite Awards. However, when it came to the televised precursors, his campaign faltered. The Insider might have gotten a lot of love, but Russell Crowe soon dominated the conversation about its excellent acting at the same time other contenders rose to the front of the Best Supporting Actor race. Soon enough, a quintet emerged and the Globes and SAG lineups were the same as AMPAS'.

The nominees were Michael Caine's inconsistently accented work in The Cider House Rules, Tom Cruise's grubby tour-de-force in Magnolia, Michael Clarke Duncan's take on the magical negro stereotype in The Green Mile, Jude Law's devilish eroticism in The Talented Mr. Ripley, and Haley Joel Osment's distillation of fear in The Sixth Sense. This last one is a case of category fraud but that didn't stop the actor from winning several awards. As for the big precursors, BAFTA went with Law, the Globes chose Cruise, Critics Choice awarded Duncan and SAG gave its prize to Caine. The Academy followed the guild's example. Would you sacrifice any of these men's nominations for a Plummer nod? I certainly would.

The Insider is available to rent from most services.