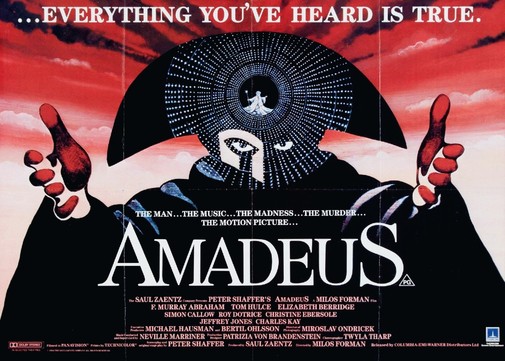

To celebrate the recent centennial of sound mixer turned movie producer Saul Zaentz, I decided to revisit my favorite of his projects, the glorious marvel that is Amadeus (the second of his three Best Picture winners). On paper, the movie may sound like the most airless and insufferable of Oscar champions. It's a musician's biopic, probably my least favorite of prestige subgenres, whose take on history is closer to feverish invention than thoughtful analysis. With a theatrical cut running for nearly three hours, the movie's a behemoth of excess in a decade when the Academy was prone to shower such things with undeserved accolades. Nevertheless, I find myself besotted by Milos Forman's 1984 Best Picture winner, its meditations on mediocrity and spiritual discontentment, its celebration of opera, the lushness of its emotions...

Peter Shaffer did the job of adapting his 1979 play and the result is a robust re-imagining of the text, seamlessly translated to the screen without denying its ties to theatrical traditional. So much so that this is one of the few film credits of legendary stage director Josef Svoboda. The Czech artist conceived the numerous stage shows we see throughout the movie, from Mozart's ebullient operas to Salieri's sepulchral piece of Baroque drama to a carnivalesque parody of all the above. In any case, Daniel Walber already went in-depth into the paper opulence of Svoboda's 18th-century stagings, so we should focus on other matters.

Rather than being the story of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's last decade, this is a confession made from the recollections of Antonio Salieri. A composer colleague of the Austrian genius, he was also his bitter rival who conspired to bring him to premature death. Such rivalry is utterly fictional by all historical records, but that's irrelevant when discussing Amadeus. Forman, Shaffer, and Zaentz aren't trying to dramatize history nor are they pretending to do so as many other prestige filmmakers would. Like Mozart's operas, Amadeus is popular art, not a school lesson. It's entertainment for the masses that isn't ashamed of that status.

Going back to another artistic titan from past centuries, the attitude Amadeus demonstrates towards history is much of the same displayed by Shakespeare when writing about English monarchy. The real-life figures are meat puppets that confer a sense of dramatic weight to what is, in essence, the character study of a psychologically complex personality. You can get away with that when the execution is this pristine, when the characterizations are this juicy. F. Murray Abraham's Salieri is among the best depictions of a dissatisfied artist in American cinema. A shattered kaleidoscope of unconvincing lies, smugness, and Machiavellian intent, this Salieri is the self-proclaimed patron saint of all mediocre people, a master of intransigence, a monster of self-flagellation.

He's a man drowning in ambition and reflective hatred, imposter syndrome made flesh. We witness as his spirit is rotted by curdled envy, the forsaking of a cruel God. Abraham portrays this sorry creature through a meticulous strategy of filigreed gesture and mellifluous oratory. The actor punctuates this with some amazing details like the epicurean Nirvana the man feels whenever he tastes a sweet treat or his passionate response to Mozart's creations. Watching the two men communicate through music is one of the movie's greatest marvels. What's perhaps most interesting is that Amadeus doesn't go out of its way to defame Salieri as the mediocre artist he proclaims himself to be. Such ill descriptions come from the man's vision of himself, not from the filmmaker's conspicuous efforts.

If Salieri's compositions pale in comparison to Mozart's, it's because most works of music can't hold a candle to that man's once-in-a-generation talent. Tom Hulce's Mozart is less impressive than Abraham's Oscar-winning work but he's just as specific and delightful when playing this larger-than-life character. There's little subtlety in the actor's filthy take on the genius composer, though that's not the mark of an undisciplined performance. There's precision to his hyena-like giggle, the palpable need for attention and parental approval. For as much as Salieri's narration attacks Mozart for a lack of monastic devotion to music, Hulce lets us see the pride of the artist, how dependent his sanity is on the creative act, and how that's the source of his ruination.

All this praise doesn't mean I'm blind to the picture's faults. The thing about re-watching movies as consistently as I do Amadeus is that the perception of the film grows along with the viewer. The dueling perspectives of Salieri and Mozart don't make sense within the narrative through-line, no matter how compelling they both are. Furthermore, the fleshy, blunt recreation of 1780s Vienna isn't without a macula. The set design and cinematography are exquisite, while most of the costumes are on the wrong side of anachronistic cinema. All those visible zippers and polyester satin look cheap instead of purposefully irreverent. This is evident when we compare the clothes to the zany wig design which strides the line between period recreation and rollicking artifice with more success.

The best of Saul Zaentz's three Oscar champions, Amadeus is the first movie I ever updated from DVD to Blu-Ray because the disc was so worn down. My love runs deep, though I realize my description of its merits may suggest a more punitive watch than the reality. Amadeus is a depiction of the toxic dynamic of two self-destructive individuals, a rhapsodic depiction of jealousy at its most soul-destroying, of lost faith at its most defeatist. However, from the propulsive cutting to the heavenly soundtrack, Amadeus never drags, never exhausts even as it presents the audience with a tragedy. Like its version of Mozart recreates his father's recriminating ghost in Don Giovanni's hellish conclusion, the movie shapes human suffering into splendorous pageantry.

Thank you, Saul Zaentz. Thank you for this endlessly re-watchable movie miracle.