"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber, is a series on Production Design.

Thursday marks 100 years since the birth of iconic French actress Simone Signoret. But how to celebrate? By my count, she was in three films nominated for Best Production Design. One of them, Is Paris Burning?, I covered way back in 2016. Another, Ship of Fools, also nabbed Signoret her second nomination for Best Actress. Unfortunately, it’s something of a bloated and maudlin mess.

Thursday marks 100 years since the birth of iconic French actress Simone Signoret. But how to celebrate? By my count, she was in three films nominated for Best Production Design. One of them, Is Paris Burning?, I covered way back in 2016. Another, Ship of Fools, also nabbed Signoret her second nomination for Best Actress. Unfortunately, it’s something of a bloated and maudlin mess.

That leaves us with La Ronde, a film made shortly before Signoret really burst into international stardom. She’s barely in it, playing a Viennese sex worker who bookends the meandering narrative. Even so, it’s her movie star quality that makes the whole thing work - that and the magic of Jean d’Eaubonne’s Oscar-nominated production design, of course. The film is Max Ophüls’s adaptation of an Arthur Schnitzler play, a circular jaunt that slips from paramour to paramour...

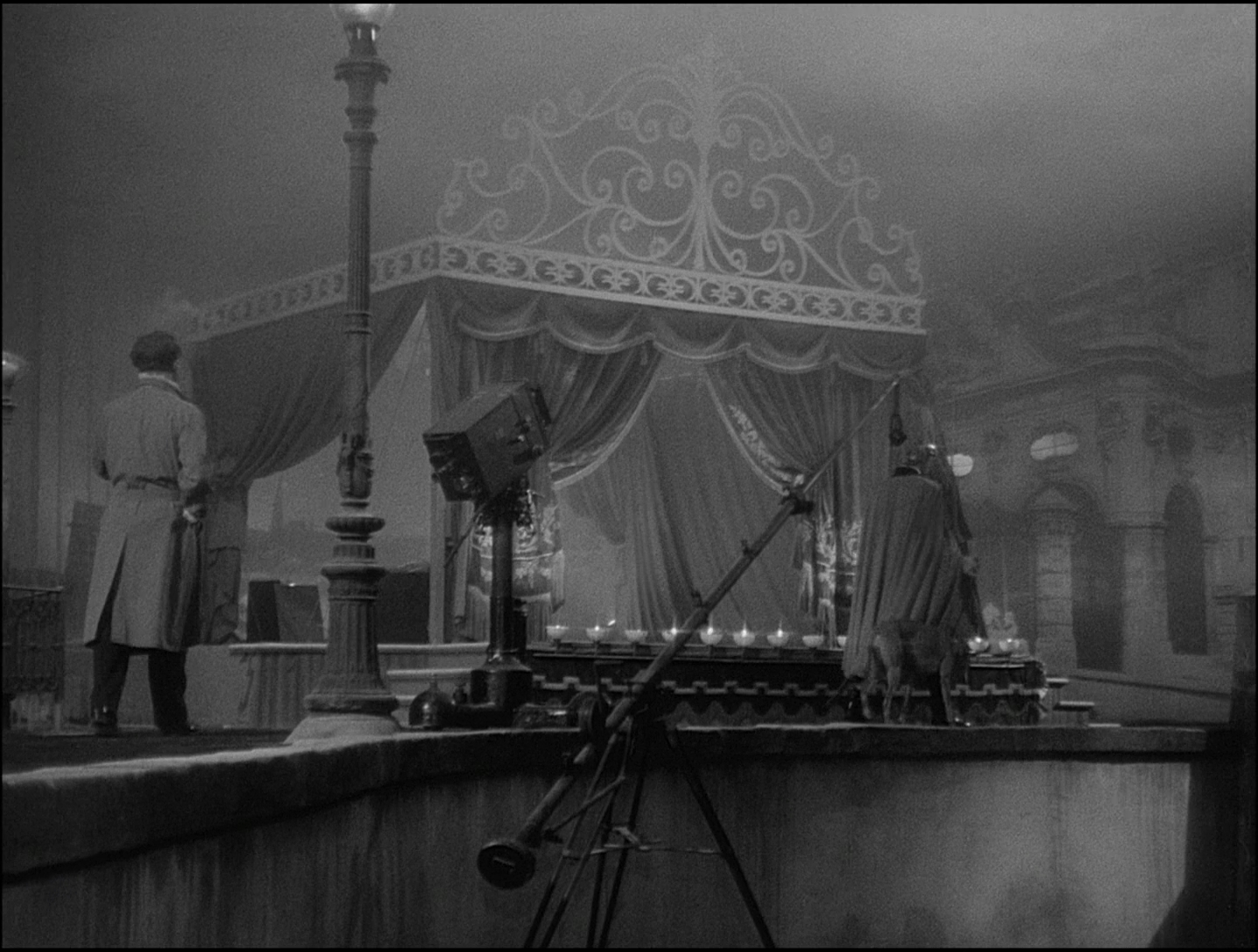

The opening sequence of the film is as elegant as it is iconic, the overture to a cinematic waltz. We are greeted by Anton Walbrook as the “Raconteur,” shifting between light Viennese song and self-aware theatrical asides. He walks right past the proscenium of a little temporary stage, of the sort used by traveling performers.

The backdrop of the stage is but a backdrop - soet of. There is actually no rear wall of the stage. We’re seeing straight through to the night sky of Vienna. Yet the Vienna we see isn’t real - it’s a matte of the city that serves as the scenery, not for this little stage, but for the film set around it.

La Ronde plays with the layers of make-believe. We’re never asked to suspend our disbelief, but rather to simply enjoy it. It’s a bit like cognitive dissonance, but its dulcet tones undermine the sonic metaphor of the phrase. When Walbrook points out the full camera set-up on this Viennese vista, it hardly feels jarring at all.

Walbrook’s destination is a carousel, the perfect metaphor for La Ronde. Round and round it goes, slow enough that the locals can hop on and off without risking too much whiplash. You may see the same beautiful toy horses each time, but the riders change faster than you might expect.

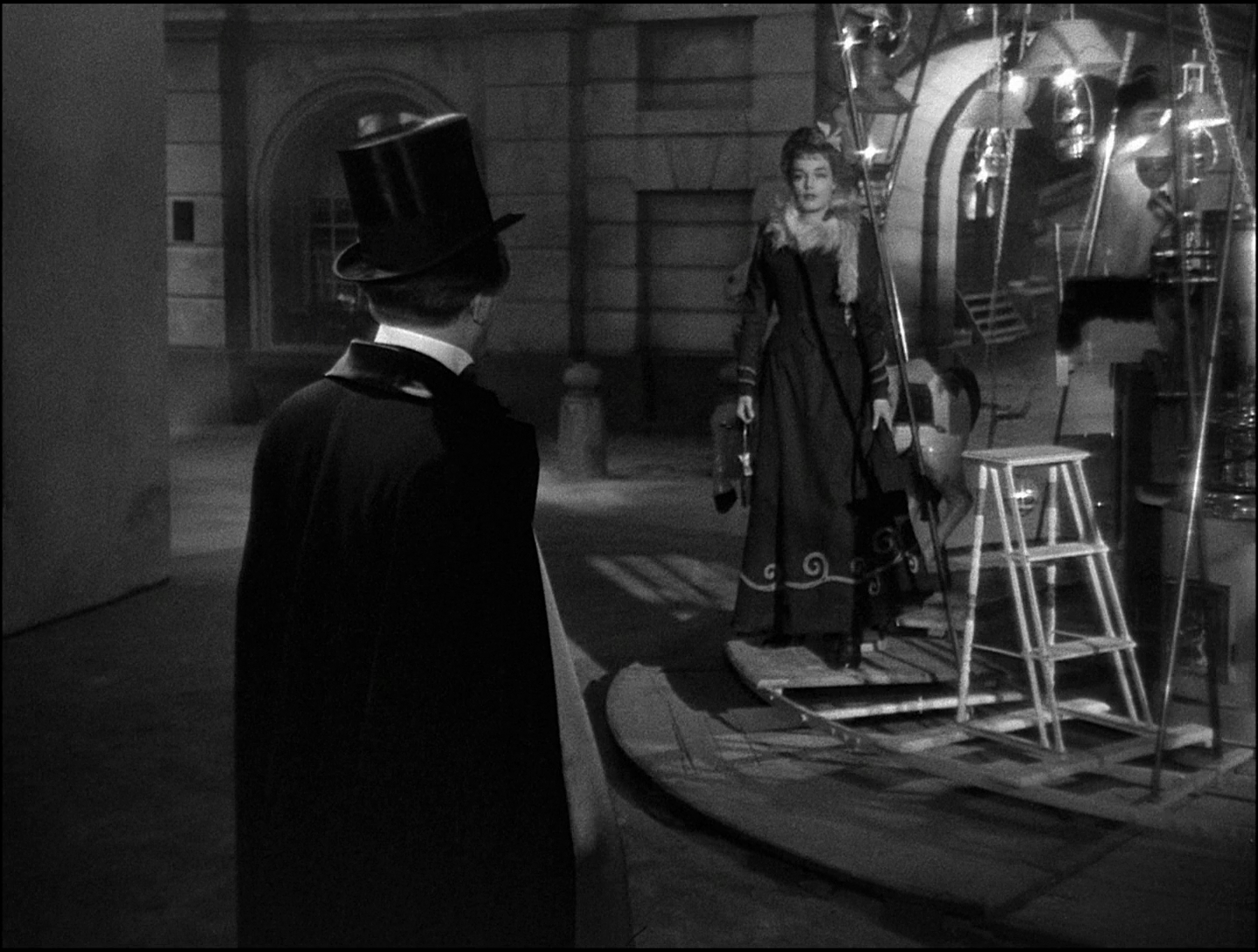

The carousel is how Signoret makes her entrance. We don’t see her climb onto the platform, which would ground her character in a reality beyond that of La Ronde. Rather, she is simply and suddenly just there.

Signoret appears to be at least somewhat more authentic a resident of this fictional Vienna than Walbrook. She approaches the carousel and its Master of Ceremonies with a bit of wide-eyed caution. But she also, instantly, carries herself like a movie star. It seems clear that Ophüls starts with Signoret because there is no confusing her presence with realism - or worse, neorealism. This is Vienna before the World Wars, before the break-up of the empire, before the cinematic discoveries of both hard truth and existential drift. There is no space for even a suggestion of the cracked, plurally occupied Vienna of The Third Man.

Which, then, is why it must be so transparently false. Ophüls understood that a faithful, realistic representation of turn-of-the-century Vienna would be a lie. But a self-aware ghost-town, a Vienna where everyone speaks French and the circus is always in town, where movie stars ride carousels and even the sewers are the perfect setting for a tryst - this is the Vienna of La Ronde. After all, despite the visual grime, Signoret and Serge Reggiani act as if it doesn’t even smell.

But this moment under the street is interrupted by Walbrook, who has donned his first disguise and trumpeted the curfew warning for Vienna’s soldiers. The young man runs off to an unseen barrack. And then, just a few seconds later, Walbrook ushers in the following night of revelry. Time is flexible in this amusement park of a town.

With that, La Ronde leaves Signoret behind for quite some time. And her return in the film’s final moments is brief, a dalliance with a count met by hazy lamplight. Frankly, it leaves us wanting more time with her. But audiences would get that soon after, with Casque d’Or, Thérèse Raquin and Les Diaboliques following right on its heels.

In the meantime, La Ronde shows how the right performer can make all the difference to a film’s tone, no matter how fleeting the role. Signoret was a perfect fit for the layered, operetta-like vibe of this masterpiece of nostalgia, collaborating beautifully with the production design and its waltz-magic.