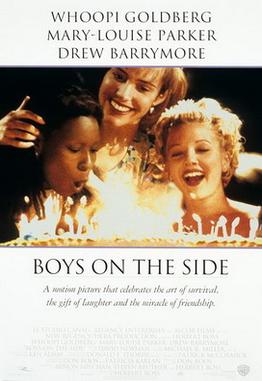

a series by Christopher James looking at the 'Gay Best Friend' trope

Incredibly disappointed I only now realized there was a road trip dramedy with Whoopi Goldberg, Mary-Louise Parker and Drew Barrymore.Long live the era of Whoopi Goldberg vehicles (aka the 90s).

Incredibly disappointed I only now realized there was a road trip dramedy with Whoopi Goldberg, Mary-Louise Parker and Drew Barrymore.Long live the era of Whoopi Goldberg vehicles (aka the 90s).

Goldberg kick-started the 90s by winning a (well-deserved) Oscar for Ghost and headlining the smash-hit Sister Act. From there, we got a string of movies where Goldberg was the leading lady. Though they varied in quality and weren’t always progressive, it was impressive to see movie after movie built around a black actress. Who else could do Eddie, Bogus, The Associate AND Ghosts of Mississippi all in 1996? We’re going a year earlier for this week’s gay best friend. No, we’re not talking about Theodore Rex (though… should we). Instead, we are talking about the messy dramedy I didn’t know I needed in my life, Boys on the Side.

Unlike in past weeks, our gay best friend (technically) takes center stage. Jane (Goldberg) is a lesbian musician looking to get out of New York and move Los Angeles after a tumultuous breakup...

She answers a newspaper ad from a nervous real-estate agent, Robin (Mary-Louise Parker), who wants a companion as she drives to California. Jane convinces Robin to take them to Pittsburgh first to visit her friend Holly (Drew Barrymore). Upon arriving in Pittsburgh, Jane finds Holly in an abusive relationship with her drug dealing boyfriend, Nick (Billy Wirth). Robin helps extricate Holly from the situation while the women all tie Nick up. After they leave, Nick falls over and hits his head on a bat, killing him instantly. The women find out about his death and high tail it out of Pittsburgh, eventually settling in Tucson.

You think that’s a lot of plot? We’re barely halfway through.

This trio lives rent free in my mind.

Robin: But this person who dumped her, she was gay, right?

Holly: Yeah, but even with gay girls there are no guarantees. They're very emotional. That's about all I know. They love uniforms and don't break their hearts.

Robin: Uniforms?

Holly: Oh, yeah, all kinds. Especially UPS.

The film’s greatest strength is its cast. The pairing of Whoopi Goldberg, Mary-Louise Parker and Drew Barrymore sounds bonkers on paper, and it is. However, it’s that unexpectedness that feeds into their characters’ relationships. Robin and Jane only meet at the beginning of the film and it takes a good amount of time for their differing personalities to warm up together. Their eventual friendship feels well-earned thanks to the actresses delightful sparring.

If one could zero in on the problem of the film, it would be the misuse of this central trio. Whoopi may be top billed and have the most screen-time of the trio, but it’s not her film. Boys on the Side does the typical 90s thing that was progressive for its time but is wildly dated now. Because she is a lesbian, she is someone everyone has to “understand,” and that’s the crux of everyone’s story. Exchanges like the one above are common throughout the film. Rather than let Jane tell us about her love or heartbreak, we are informed about her backstory through two white women trying to make sense of her interiority. This is why, though she is a lead, Jane is a classic example of the gay best friend trope. They exist as facilitators of the straight character’s journey to acceptance and understanding.

Where's their 90s rom-com?Boys on the Side was directed by Herbert Ross and written by Don Roos, two talented men whose competing visions don’t often play well together. It shows up on screen. The playful tartness present in The Opposite of Sex is drenched in Ross’ schmaltz, hoping to make every moment sweet and syrupy. Roos wrote characters with edge, but Ross wants them to be more cuddly.

Where's their 90s rom-com?Boys on the Side was directed by Herbert Ross and written by Don Roos, two talented men whose competing visions don’t often play well together. It shows up on screen. The playful tartness present in The Opposite of Sex is drenched in Ross’ schmaltz, hoping to make every moment sweet and syrupy. Roos wrote characters with edge, but Ross wants them to be more cuddly.

Even more than that, Roos writes his character as sexual and Ross seems to direct the actors to be more abstractly “in love” as friends. Jane and Holly are friends because they used to have a sexual relationship that turned into friendship. Holly doesn’t identify as gay, Jane seems to be someone she experimented with. (Side-note: What would a lesbian rom-com with Drew Barrymore and Whoopi Goldberg have looked like in 1995? I demand a prequel.)

Jane’s attraction to heartbreak doesn’t always lead her to straight girls, but it sometimes does. Over the course of the year or so the movie takes place, Jane’s affections appear to turn to Robin. Whoopi does a great job conveying Jane’s sensitive side, particularly when Robin buys Jane a piano and Jane sings “My Funny Valentine.” Just as it seems the movie will delve into Jane’s sexual feelings for Robin, it backs off to be more about friendship.

Remember how I said there was a lot of plot to get to, I skipped ahead a lot by jumping to the piano. While on the road to California, both of the white women in the car have medical updates. The first is that Holly is eight weeks pregnant (we’ll get into that more later). More importantly, Robin is hospitalized for pneumonia once they reach Tucson, Arizona. It’s not just a case of a bad cold though. We learn Robin has AIDS, which she got from a male partner back in New York.

Just two years after Philadelphia, movies were starting to talk about AIDS, but it still was very ghettoized. The way Boys on the Side handles Robin’s HIV diagnosis is interesting and somewhat revolutionary. In establishing she got it through heterosexual sex, the film acknowledges that the disease can touch more than gay men, even though that’s the disease’s primary target. Perhaps because a straight(ish) woman contracted AIDS, the film doesn’t feel the need to stigmatize or lecture her on her sexual practices. However, this sets a good baseline. It’s not Robin’s fault she contracted HIV, just like it’s not the fault of any of the gay men who died of AIDS during the ongoing crisis. It’s a disease that ravages its victims and people deserve to be cared for and loved as they go through their final days.

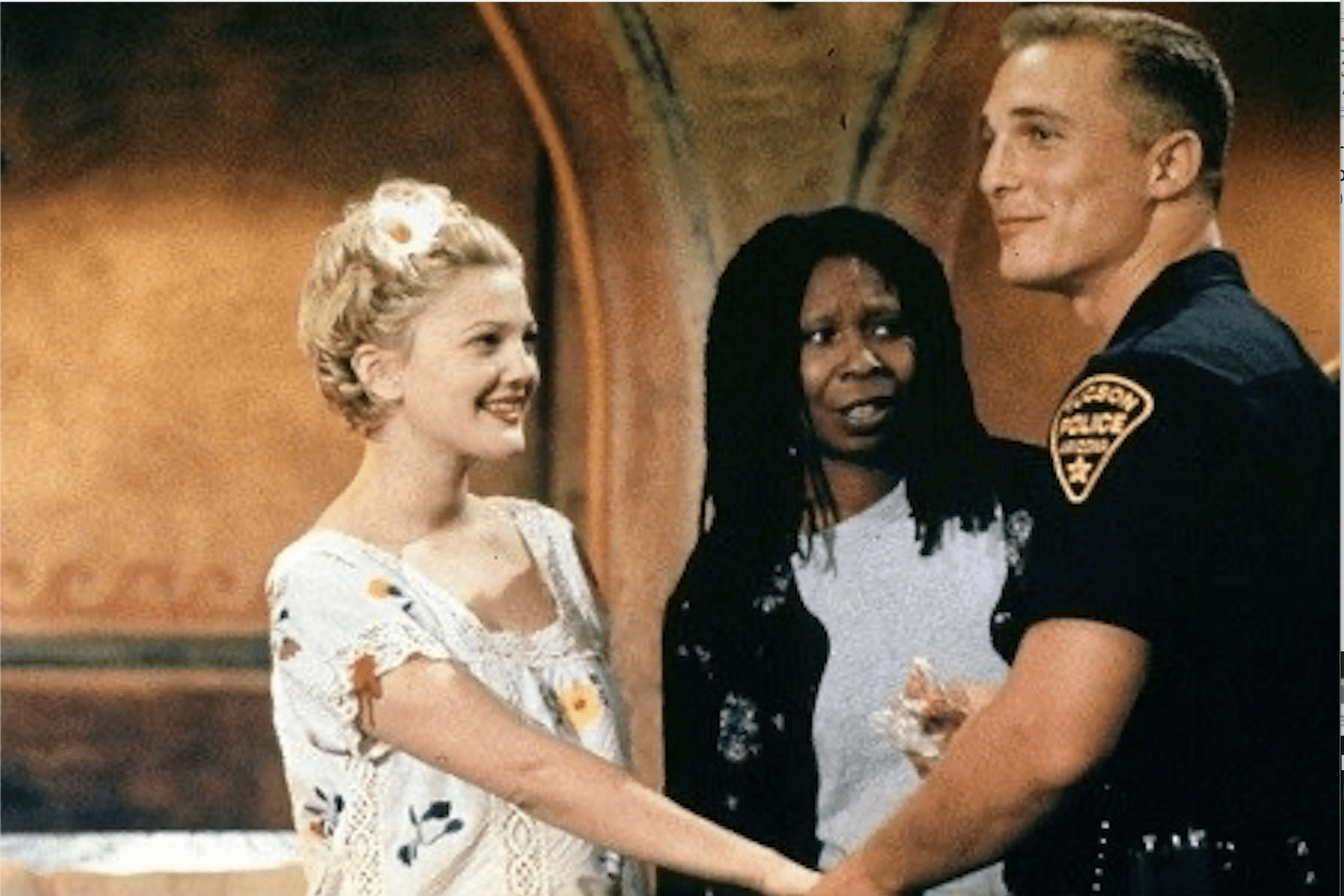

Whoopi and Drew are perfectly embodying both my reactions when I saw Matthew McConaughey appear on screen.

Whoopi and Drew are perfectly embodying both my reactions when I saw Matthew McConaughey appear on screen.

After the initial hospitalization, the women set up shop in Tucson. Holly falls for a local cop by the name of Abe Lincoln (Matthew McConaughey… yes really). Love is also in the air for Robin, who attracts the attention of a local bartender, Alex (James Remar). After some flirting, the two make their way to the bedroom, which causes Robin to freeze up. How will she navigate this situation, living with HIV. She tries to shut down the sexual contact, but Alex continues to make a move on her. Robin continues to insinuate that she has something to tell him, but he continues kissing her, softly saying he knows her secret. Robin bolts upright. How does he know? Alex tells Robin that he planned on using “a rubber” and was still interested in having sex with her, despite her HIV status. She still wants to know how he already knows. Alex tells her that he had “guessed” during a conversation with Jane. Too angry to move forward, Robin asks Alex to leave.

For 1995, having a scene where a man lusts after a woman, knowing full well her HIV status, is powerful. Casual depictions like these help normalize sex after diagnosis, as well as safe sex. Though Robin does not go through with the act, Alex is important in reminding her that she can still be sexual, even with a sexually transmitted disease. The news and media at the time had a habit of depicting people with HIV as lepers or diseased, rather than actual people who still have desires, wants and needs. Boys on the Side doesn’t give Robin a full sex life after her diagnosis. However, it establishes that (a) she could have a sex life, (b) it would be safe for her to have sex with proper protection, and (c) people could still desire someone even if they knew they were HIV positive. These assertions may appear standard in 2021, but for 1995 it was quietly progressive.

With every progressive moment is a less progressive moment. It feels out of character that Jane, the lone queer character, would be the one to betray Robin’s HIV status to someone. It feels like a means to an end to drive Jane out of the house for story convenience. However, betraying someone’s HIV status is akin to outing them without their consent. It’s terribly wrong, even if it's done through inflection rather than outright gossip. How would Jane not have understood the gravity of this reveal? This wedge is driven only so the characters have something to fix in the final act, and the two eventually rekindle their friendship as Robin’s health worsens. However, this underscores the central problem even further. Jane isn’t well defined enough as a character for this to seem plausible or dramatic enough. It just reads as underwritten. Once again, the queer character only exists as a storytelling device on the straight, white woman’s journey.

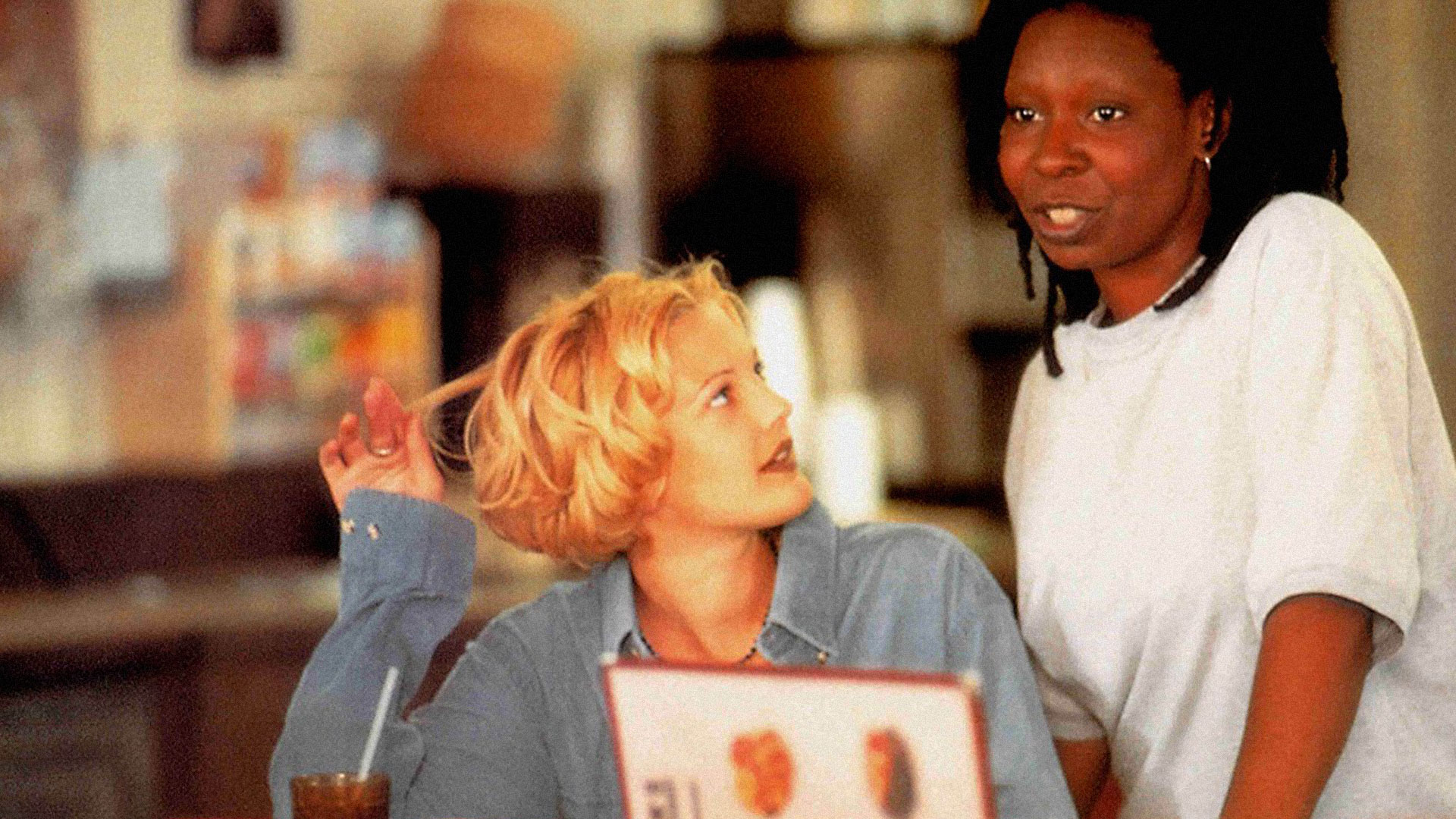

Jane (Goldberg) and Robin (Parker) first bond on the road while they watch "The Way We Were" in a wonderful scene.

Jane (Goldberg) and Robin (Parker) first bond on the road while they watch "The Way We Were" in a wonderful scene.

Massarelli, Prosecuting Attorney: Are you a lesbian too, Ms. Nickerson?

Robin: No sir but at times I understand the inclination.

--------------------------------

Robin: I don't know what it is but there's something that goes on between women. You men know that because it's the same for you. I'm not saying one sex is better then the other. I'm just saying, like speaks to like. Love or whatever doesn't always keep. So you found out what does, if you're lucky.

Just when you thought Boys on the Side was done with tricks, they kicked it into gear in the final act. Holly confessed to Abe that she murdered her abusive ex-boyfriend, Nick. The only thing Abe loves more than Holly is the law, so he has her arrested and she awaits murder trial in Philadelphia. Don’t worry though, he promises he’ll marry her once she’s out. Thanks Abe, swell guy.

Robin and Jane are drawn back together to act as witnesses for Holly’s case. While there, Jane gets grilled for being a lesbian and her relationship with Holly is seen as a reason Holly may have murdered Nick (a stretch, we all agree). Jane gets to be more righteously defiant on the stand. Meanwhile, Robin gets the prime tearful monologue spot on the stand. This is her moment to share “what she has learned from the lesbians” (™). While much of it is framed around “understanding,” this is a nice moment to frame Robin’s fraught friendship with Jane. It’s not the typical story of a homophobe “understanding” to love their gay friend. This is about a woman “understanding” what attraction between women is and how our sexualities can morph and confuse us. “Love or whatever doesn’t always keep.” There’s no one size fits all version of love. Though Robin and Jane were never sexual, there was a love between them, even if it may have been just platonic love, not romantic love. Or maybe it was romantic. This speech leaves enough unsaid to the audience in a strange, but somewhat beautiful way. The mechanics of Jane and Robin’s dynamic belongs to them and them alone.

Celebrate! We're almost done with describing this winding road of a movie.

Celebrate! We're almost done with describing this winding road of a movie.

Elaine: I do the best I can, honey. I know it's not enough, and I'm sorry. But that's what you get in life, you know? You get whoever you end up with. Whoever is willing to stick by you, and fight for you, when everyone else is gone. And it ain't always who you expect. But you just have to make do.

We’re still not wrapped up, but we’ll move at breakneck speed. Holly gets offered involuntary manslaughter with only a few months of prison, which she takes. As the verdict is read, Jane collapses from a lung infection. In the hospital, Jane and Robin finally reconcile. We flash forward to the birth of Holly’s baby. Abe (yes, he’s still around) and Jane run to meet the baby only to find out the baby is black (aka not Nick’s baby). They bring the baby home, beaming from ear to ear. There to greet them is a wheelchair bound Robin, in the late stages of AIDS. She is surrounded by all of the women’s family and friends (including her scene stealing mother Elaine, played by Anita Gillette). In her final moments, Jane and Robin perform a touching rendition of Roy Orbison’s “You Got It.” It’s a touching ending to a movie filled with laughter, tears, confusion and joy.

A few days removed from watching Boys on the Side and I still can’t quite believe it was made in 1995. In so many ways, the film is dated. Yet, it’s more than well-meaning too. It wants to try and tackle a number of tricky topics and have fun while doing so. It’s as if The Chick’s “Goodbye Earl” had an AIDS subplot. Roos’ script could’ve maybe flourished under a more sure directorial vision with greater command of tone. Still, it’s wild to see a wide release movie that centers around a black, queer woman. Sure, it’s still told by cis white men and starring mostly cis white women. Progress isn’t always what one expects, but we as a culture just have to make due.

Previously in Gay Best Friend

pre stonewall

- Plato (Sal Mineo) in Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Sebastian Venable in Suddenly Last Summer (1959)

- Calla Mackie (Estelle Parsons) in Rachel Rachel (1968)

post stonewall

- Erich (Norbert Weisser) in Midnight Express (1978)

- Toddy (Robert Preston) & Squash (Alex Karras) in Victor/Victoria (1982)

- Dolly Peliker (Cher) in Silkwood (1983)

1990s and the 2000s

- Sammy Gray (Steve Zahn) in Reality Bites (1994)

- Gareth (Simon Callow) and Matthew (John Hannah) in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)

- George Downs (Rupert Everett) in My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997)

- George Hanson (Paul Rudd) in The Object of My Affection (1998)

- Bill Truitt (Martin Donovan) in The Opposite of Sex (1998)

- Robert (Rupert Everett) in The Next Best Thing (2000)

- Patti (Sandra Oh) in Under the Tuscan Sun (2003)

- Nigel (Stanley Tucci) in The Devil Wears Prada (2006)

- Wallace Wells (Kieran Culkin) in Scott Pilgrim vs the World (2010)

the now

- Abby Gerhard (Sarah Paulson) in Carol (2015)

- Oliver (Nico Santos) in Crazy Rich Asians (2018)

- Duncan (Pete Davidson) in Set It Up (2018)

- Jack Hock (Richard E. Grant) in Can You Ever Forgive Me (2018)