I make no secret that I'm a Joan Crawford fan. After all, I've already waxed poetic about the star's stellar 1947 and her turn in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?. However, I've never written about Crawford's career pre-Oscar win. Since we're celebrating 75 years since that victory, it feels like an appropriate time to examine the actress' long road to Oscar, the misconceptions about her legacy, the complexities of her contemporary popularity. If you want to read more about the 18th Academy Awards, check out Baby Clyde's wonderful overview of the ceremony and the race for gold. Now, it's time to focus solely on that year's Best Actress champion…

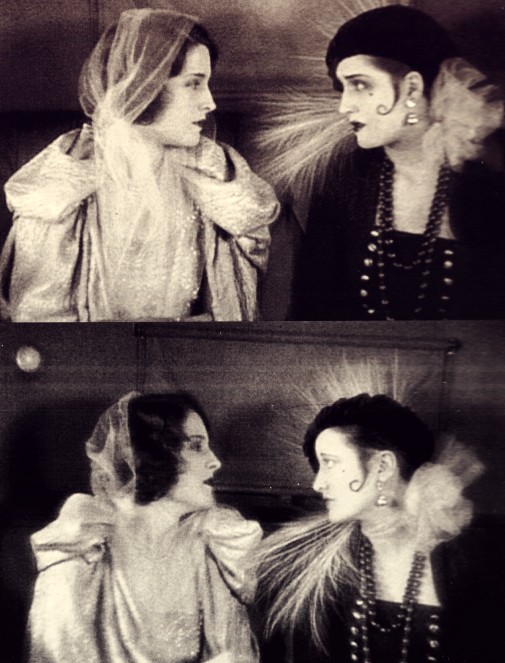

Born in Texas as Lucille Le Sueur, the future Joan Crawford wasn't raised with a silver spoon in her mouth. She started working to earn money when she wasn't yet 10-years-old and her rise to Hollywood fame was by no means a tale of instant success. Starting her career as a chorus girl, Crawford first dreamed of dancing for a living, while acting was a vocation that came later when she was hired by MGM. At the time, any aspiring starlet had to contend with a studio focused on promoting other big names like Marion Davies and Norma Shearer. In 1925, Crawford even worked as Shearer's body double in Lady of the Night. In that flick, the First Lady of MGM played twins so Crawford was her stand-in, the unknown actress later obscured by the star in post-production.

LADY OF THE NIGHT (1925)

LADY OF THE NIGHT (1925)

After years of playing bit parts and uncredited labor as an extra, Joan Crawford started getting some bigger roles as the era of the Silent Movie drew to a close. In 1927, she impressed many with her performance as the leading lady to Lon Chaney's armless criminal in the circus-set The Unknown. Seeing their contract player's newfound popularity, MGM was quick to capitalize and started working on making a new star out of her. In a couple of years, Joan Crawford went from an anonymous background actress to a star in progress. This newfound acclaim was solidified by her participation in several Billy Haynes star vehicles, college comedies that showcased a lighter side of Crawford's screen persona.

OUR DANCING DAUGHTERS (1928)

OUR DANCING DAUGHTERS (1928)

Nonetheless, if I were to pinpoint the moment Joan Crawford became a star, 1928's silent Our Dancing Daughters would be it. She transformed herself into the apex of the flapper archetype just as the 20s were coming to an end, a modern woman that electrified the screen with an image that viewers could relate to. Dancing furiously, smiling with pain glinting in her sad eyes, her spectacular characterization and feverish energy were admired by moviegoers all over. By the end of 1929, Crawford had made her last silent, Our Modern Maidens, let go of the flapper persona and embraced the talkies. This willingness to adapt was key to her success as well as its longevity. Hers was a career that spanned most of Hollywood's big studio era because, instead of fighting against the changing tide of culture, she went with it, transforming herself according to the demands of the moviegoing audience.

Her early approach to professional life may have been marked by stoic acquiescence in regards to the studio's decisions and the industry's changes but her presence in front of the camera exuded strength, a survivor's force. Put her in a melodrama and she cuts through the froth like a hot knife cuts butter. This reflected her own experience outside the fantasy of the silver screen. Joan Crawford was a self-made woman whose class origins informed her star persona even as she and MGM tried to erase those very same details. While deadly glamorous, the actress' luminous elegance was never presented as necessarily natural. In her films, glamour and sophistication were seen as constructs, things one could be trained into being, learned to embody. Instead of an untouchable idol, her Great Depression popularity was tied to the idea that the viewer's wishes could come true.

LETTY LYNTON (1932)No working-class person could imagine themselves as the patrician etherealness of Shearer. In contrast, it's easy to see why someone could look at Crawford and see proof that aspirational ambitions aren't bound to fail. Sometimes, triumph is at the end of the hard road of life as the elusive American Dream so duplicitously promises. That's also what Crawford's shining screen presence promised and what she looked for when choosing projects. In her own words, the actress' strategy for picking roles focused on audience identification first and foremost. On-screen, she was thus the self-made survivor and the fallen woman crystalized in celluloid, ready to materialize her fans' escapist dreams. Joan Crawford was also a style icon. Adrian's ruffled organdy dress designed for Letty Lynton is especially famous, having started a small fashion revolution and prompted many copycats that spanned from royalty to the common woman.

LETTY LYNTON (1932)No working-class person could imagine themselves as the patrician etherealness of Shearer. In contrast, it's easy to see why someone could look at Crawford and see proof that aspirational ambitions aren't bound to fail. Sometimes, triumph is at the end of the hard road of life as the elusive American Dream so duplicitously promises. That's also what Crawford's shining screen presence promised and what she looked for when choosing projects. In her own words, the actress' strategy for picking roles focused on audience identification first and foremost. On-screen, she was thus the self-made survivor and the fallen woman crystalized in celluloid, ready to materialize her fans' escapist dreams. Joan Crawford was also a style icon. Adrian's ruffled organdy dress designed for Letty Lynton is especially famous, having started a small fashion revolution and prompted many copycats that spanned from royalty to the common woman.

GRAND HOTEL (1932)

GRAND HOTEL (1932)

Considering all this, it may seem strange to see that Crawford didn't score an Oscar nomination until Mildred Pierce. In 1932, she not only starred in a Best Picture winner, Grand Hotel, but wiped the floor with her costar Greta Garbo. I'm a huge fan of that Scandinavian goddess but her depressed ballerina doesn't compare to Crawford's spunky stenographer. Our star considered the flick to be the greatest film she ever made and, while I would disagree with that assessment, it certainly features one of her best turns. She savors every line with shameless pleasure, imbues each gesture with portentous meaning. To explain her snub, we must understand studio campaigning, what was seen as good acting and what publicity could make to a star's perceived prestige.

To be a fashion icon isn't something associated with great acting talent, then or now, and many tend to look down at those who indulge in those "feminine" interests. The same can be said about Crawford's populist appeal, her relatable screen persona, and constant appearance in gossip columns thanks to a myriad of turbulent romances with high-profile actors. Furthermore, the 30s were a time when what was considered good film acting still owed a lot to a theatrical tradition and ideas of transformation. It's no wonder many of the early Best Actress victors were stage sensations before they were Silver Screen Sirens. Crawford was neither a monument of the industry, a living institution, à la Mary Pickford (one of Crawford's mothers-in-law), nor was she a prestige tragedienne of the Broadway stage like Helen Hayes.

When a great actress is also a great celebrity, Hollywood can often take their talents for granted and lose sight of their craft, blinded by the glitz and the apparent simplicity of crowd-pleasing fare. MGM didn't do her any favors either. While their marketing emphasized Crawford as a way to sell tickets, they did not campaign her for awards, preferring to promote other players instead. After being dubiously named box-office poison in 1938, Joan Crawford further saw how her studio gave away the roles she craved to Greer Garson, a new name in their roster. While Crawford kept being saddled with less prestigious material, the other woman got to play great ladies of history, classic literary heroines, and inspirational figures. To this day, AMPAS' loves such roles.

A WOMAN'S FACE (1941)

A WOMAN'S FACE (1941)

All that being said, it's true that Joan Crawford might have earned a nomination in 1939 had she campaigned as a supporting player. Her bitchiness in The Women is insuperable, a queenly show of sharp cattiness that makes deceitfulness look appealing. That film also paired the star with George Cukor, her favorite director and the man responsible for the best of her later films at MGM. While Crawford didn't look with much fondness at the first half of the 40s, what she called her "middle years", I'd point to 1941's A Woman's Face as one of her greatest pictures and what should have been another Oscar nod. Remaking a Swedish Ingrid Bergman flick, Cukor and Crawford composed a study of shattered identity. Once again, beauty and glamour are constructs when played by the actress but, here, they are also jagged and dangerous.

Apart from that exception, I'd agree with Crawford's unhappy feelings towards this part of her career. MGM was simply unequipped and unwilling to perpetuate her stardom. A couple of dreary, if entertaining, World War II-themed oddities, Reunion in France and Above Suspicion, were her last flicks for the studio that had been her home since the mid-1920s. At considerable expense, she bought out her contract and went to Warner Bros. where she demanded greater power in the selection of projects. Her days of acquiescence were over and, for two years, she turned down every role offered. This was risky for her career and her professional longevity, but Crawford also knew what roles were right and what weren't. When she found the perfect part, the actress went as far as doing screen tests to win over director Michael Curtiz. He reportedly preferred Barbara Stanwyck, but Crawford convinced him.

The project was Mildred Pierce, a sanitized adaptation of James M. Cain's novel about an ambitious independent woman living through the Great Depression. Building a restaurant empire, Mildred tries to win the affections of a rebellious daughter through wealth, but ends up betrayed, desperate, with a smoking gun in her hand. I'm not particularly interested in litigating Crawford's domestic life, but it must be said that paired with all the financial and career-focused details of the plot, Mildred Pierce's portrayal of a spiky mother-daughter relationship may have hit close to home. Whatever past trauma or present abuse she might have suffered and inflicted, Crawford channels it all into this woman, her ultimate role, her greatest tour de force.

MILDRED PIERCE (1945)

MILDRED PIERCE (1945)

This film noir classic is the culmination of Joan Crawford's life up until that moment. So undeniable is she that an industry that had ignored her for decades finally paid attention. Unlike MGM, Warner Bros. put all its force in guaranteeing Crawford the nomination which also helped. Come Oscar night, she was battling for the trophy with three previous winners – Ingrid Bergman, Greer Garson, Jennifer Jones – as well as Gene Tierney's atypical turn as the psychopathic femme fatale of Leave Her to Heaven. After years of hard work, Crawford finally won and, master of publicity as she was, the actress received her prize at home after a miraculous recovery from a very sudden, very mysterious, illness.

This is a long write-up, one of the longest I've ever done for The Film Experience, and I think Joan Crawford is worth the work. The main reason why this wealth of detail felt necessary is the fact that her troubled legacy tends to overshadow her work, her acting chops, her great movies. The actress' studio switcheroo in 1943 was a ballsy move that signaled a considerate effort to tackle difficult material worthy of her talents. She chose each Warner Bros. movie specifically and made them into some of the most interesting American pictures of the postwar years, maintaining her relevancy well into the 1950s. Joan Crawford is more than a camp joke, she's more than the Gorgon of Mommie Dearest or the tragedy of Feud.

I remember reading a review of Ryan Murphy's exhumation of Crawford's legend where someone implied that Jessica Lange played a scene from Baby Jane with the sort of nuance and skill that were beyond Crawford, always more of a vain star than a good actress. Nearly four years after that show's airing, I still feel outraged about such statements. Why had Joan Crawford's legend, her great filmography, resulted in such a dreadful modern opinion? What can one do to change that? This piece, celebrating the 75th anniversary of her well-deserved Oscar victory, is my attempt at doing that and maybe convince some people to give her a chance. Joan Crawford's filmography is worth your time and one can learn immensities about the history of Hollywood and the Oscars just by watching her movies.