Please welcome guest contributor Brent Calderwood...

by Brent Calderwood

I first saw Bound in 2000 at a special screening at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco, four years after its initial release. The audience was rapt, cowering in their seats or nervously laughing in all the right places. Back then, my college friends and I were so desperate for LGBTQ content that we’d hold house parties to watch pirated VHS tapes of the original ten-episode British series Queer As Folk, converted from imported PAL-format tapes by a friend of a friend in our school’s AV department. Given the dearth of queer representation, we convinced ourselves that we loved everything we saw no matter what, down to the neutered gay characters serving up puns on Will & Grace. Fast forward to 2021—would Bound live up to my memory and expectations?

I was nervous about how Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s debut would hold up 25 years after it was first released, but as it turns out I didn’t need to worry. The 1996 noir, which just began streaming on Hulu, remains as fresh and edgy as ever...

At Bound’s center are two women: Violet (Jennifer Tilly), who lives in the Chicago penthouse of her mafioso boyfriend, and Corky (Gina Gershon), a magnetically swaggery ex-con who’s been hired by the building manager to paint and repair the vacant unit next door. Within days of meeting in the elevator, Violet and Corky start up a steamy affair and are soon hatching a plan to disappear with the $2 million that Violet’s violent boyfriend, Caesar (Joe Pantoliano), has locked in his office to deliver to his boss. It’s a familiar crime film framework, but that familiarity is what makes every unexpected twist so delicious. It gives Bound a grounding for the actors, directors, and cinematographer to go to extraordinary places.

Bound was the right combination of creatives at the right time. Tilly had been Oscar-nominated two years earlier for her supporting role in Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway (1994), and although her kittenish voice would soon be more closely associated with the titular puppet in Bride of Chucky and Bonnie on Family Guy, the Wachowskis had her dial down her idiosyncratic sound to a dramatic, sleepwalky whisper. Gershon had appeared the previous year in the already-infamous Showgirls, but her cocksure performance helped her emerge from that campy dumpster fire with her acting cred intact. And Pantoliano is perfectly cast as Violet’s boyfriend; not movie-star handsome, he’s menacing and unhinged enough to be a believable threat to his underworld enemies but charming enough to hold our interest and not be overshadowed by his co-stars.

In their directing debut, the Wachowskis made all the right decisions. The low-budget film was financed by Dino De Laurentis, whose company had previously produced The Last Seduction, another excellent female-led erotic noir. The Wachowskis hired feminist writer and “sexpert” Susie Bright as a consultant on the film; together they agreed that the central sex scene between Tilly and Gershon should be filmed as one continuous take, giving it immediacy and preventing De Laurentis from splicing in porn-style body double shots for foreign markets. The scene is sexy without being coy, and maintains the subject-position of the women rather than feeling exclusively tailored to a heterosexual male gaze.

The camera shots, lensed by Bill Pope and edited by Zach Staenberg, are bravura without being too showy. When Caesar, who’s a money launderer, ends up literally washing a victim’s blood off thousands of hundred-dollar bills, hanging them to dry on paper clips and hand-ironing them so he can deliver the loot to his boss, the camera moves through a roomful of money fluttering like leaves on trees. Another shot pulls out from the black barrel of a gun resting on a table with whisky being poured into a glass beside it. Several set-ups are clear nods to Hitchcock, Polanski, and Kubrick—a common trap for first-time directors, but it works here: The climactic last half hour successfully ratchets up the tension with visual parallels to Psycho, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Shining. These practical camera effects all work at least as well as, if not better than, the CGI moves the Wachowskis would become known for in future films like The Matrix and Cloud Atlas.

Viewed in 2021, it’s interesting to think how Bound would be made differently today. As an indie film with two queer women at its center, it would most likely be produced for cable or one of the streaming platforms, and whereas in 1996 it was hard to cast, big-name actresses would now be clamoring for the chance to play central characters with complex sexual identities. There would definitely be more CGI, potentially taking the viewer out of the here-and-now and into the uncanny valley. It would also be a touch less violent—the grisly gun and torture scenes in Bound are as expertly shot and tensely edited as anything else, but squeamish and seasoned viewers alike will no doubt be covering their eyes and ears in several spots.

Violence is relative, though. Back in 1996, even at San Francisco’s Frameline International LGBT Film Festival, at least half of all “gay films” ended with gay-bashing, murder, or terminal illness, and “lesbian films” often ended with one or both women finding or returning to boyfriends. Bound was ahead of its time in presenting multiplex-ready queer content and keeping its women characters central to the end, and it still feels ahead of its time today. In 2015, the Oscar-nominated Todd Haynes-Cate Blanchett film Carol was credited for its beautifully shot, non-porny sex scene between two women and for being one of the first mainstream lesbian love stories with a happy ending. Check out Bound for yourself to see if it doesn’t deserve credit for getting there first. Those films came out 19 years apart; hopefully the next worthy competitor won’t take that long.

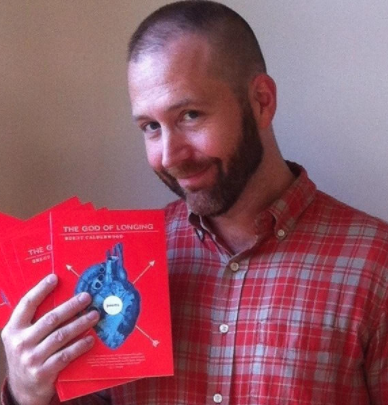

Brent Calderwood is a contributing writer to Rolling Stone and Noir City magazines, with past credits in Out magazine and the Chicago Sun-Times. His book, The God of Longing, was an American Library Association selection for 2014 and includes pop culture-centric poems about Alfred Hitchcock, Gloria Swanson, Margaret Cho, and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Follow Brent on Twitter or Instagram.

Brent Calderwood is a contributing writer to Rolling Stone and Noir City magazines, with past credits in Out magazine and the Chicago Sun-Times. His book, The God of Longing, was an American Library Association selection for 2014 and includes pop culture-centric poems about Alfred Hitchcock, Gloria Swanson, Margaret Cho, and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Follow Brent on Twitter or Instagram.