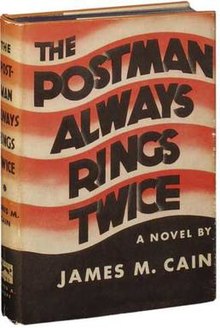

The Lana Turner / John Garfield classic The Postman Always Rings Twice opened 75 years ago in US theaters. Based on James M. Cain’s bestselling 1934 novel about a wife who colludes with her lover in an attempt to pull off the perfect murder, Postman had to gloss over the grime to get past the censors, but it remains one of the best-loved film noirs of all time, and its huge box office success has been credited with cementing Turner’s status as a top-billed star.

While The Film Experience isn't set to celebrate the movies of 1946 until June, Postman belongs to multiple years. Here's a rundown of the four most famous screen adaptations of Cain’s crime novel, listed more or less in order of their critical reputation today...

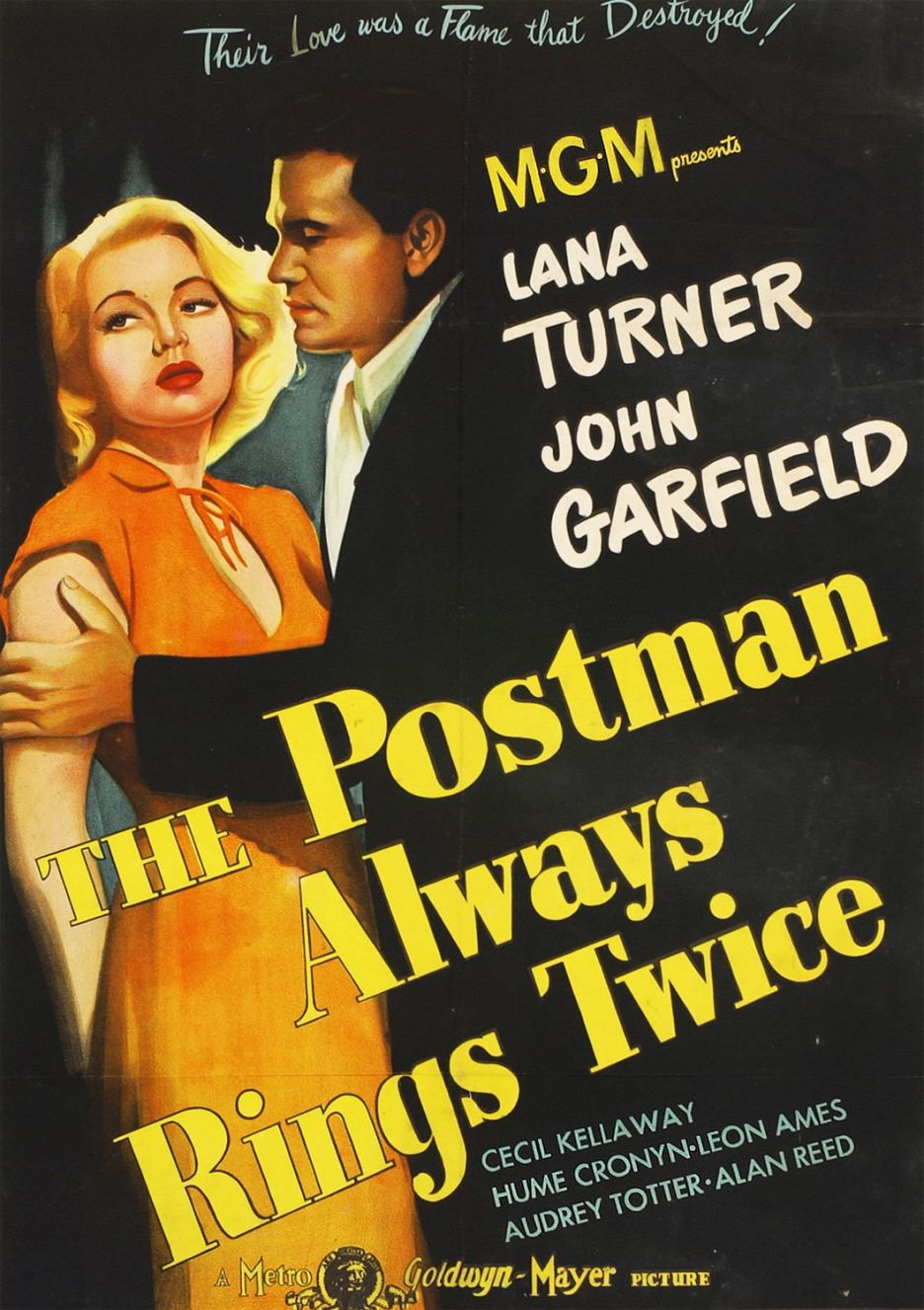

1. The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) starring Lana Turner and John Garfield.

The best-known version gave Lana Turner one of the most famous entrances in Hollywood history, scantily clad in summer whites from turban to open toe, and helped her graduate from teeny “sweater girl” roles in Andy Hardy-esque confections to bona fide stardom. Consider it: Without Postman, we might not have Turner’s later, life-layered performances in lush and sudsy Technicolor classics like Peyton Place and Imitation of Life. John Garfield as the rugged drifter antihero was borrowed by Warner Brothers and lends the MGM production a hint of gritty realism; in a career cut short by the blacklist and heart trouble, Postman remains his most famous film, but his favorite (and mine too) was 1950’s The Breaking Point—a retelling of To Have and Have Not that Ernest Hemingway identified as the best adaptation of any of his stories.

This being MGM, Postman’s supporting cast is also top-notch. Look for a young and surprisingly sexy Hume Cronyn as a whip-smart lawyer, as well as a brief but pivotal scene with Audrey Totter, a versatile actress who deserved to be an A-list star and is still worshipped by noir and B-movie fans.

2. Ossessione (aka Obsession, 1943) starring Clara Calamai and Massimo Girotti.

More a reimagining of Postman than a strict adaptation, Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione makes Cain’s central murder a crime of passion rather than pragmatism. In spite of narrative liberties and poetic license, Ossessione’s sweaty eroticism gets nearest to the spirit of the original, and Clara Calamai’s restless trattoria cook comes closest to the strong-willed creature in heat that the novel’s narrator describes:

“She looked like the great grandmother of every whore in the world.”

Within an hour of serving lunch to the bedroom-eyed wanderer played by Massimo Girotti—who looks like a slightly better-looking older brother of Michelangelo’s David—the two are basking in the afterglow. “You won’t leave me, will you?” moans Calamai, and after dinner while her husband is outside firing his gun at mating cats, she’s already planning her escape. Ossessione punctuates stretches of silence with street noise and source music (an amateur opera competition, an accordion dance band) and minimal scoring, so when orchestration does come in, as in the tense final moments, it generates a heightened realism that feels truly tragic.

Ossessione is historically important for a few reasons: It’s often credited as the first example of Italian neorealism, excepting when Visconti and his cinematographers give Girotti the diaphanous lighting and lingering gaze that’s normally lavished on stars like Lana Turner. Apropos of which, Ossessione is also important for providing an early example of homoeroticism and gay subtext in film: Visconti’s cowritten screenplay includes a street performer named “the Spaniard” who’s absent from the book; portrayed with unsentimental tenderness by Elio Marcuzzo, he’s as desperately in love with Girotti as both Calamai and the camera are. A final note: Like the original French adaptation, this Italian version was also almost destroyed, by Fascists in this case instead of Nazis. Luckily, Visconti held onto a duplicate negative, and the film was finally distributed outside of Italy in 1976.

3. The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981) starring Jessica Lange and Jack Nicholson

In an effort to capture the Depression-era setting of the 1934 novel, this version transports the characters from the California coast (the ocean plays a critical role in the novel and 1946 film) to a dreary, mountain-surrounded landscape with authentic-to-the-period cars and architecture. Sadly, that means pristine restored Ford Roadsters and a Craftsman-style home that’s appointed with lush Arts and Crafts decor, looking more like a cozy bed-and-breakfast than the greasy hamburger stand described in the novel.

Screenwriter David Mamet’s long, stagy scenes borrow from Cain’s dialogue but eliminate the protagonist’s voiceover narration; this, coupled with director Bob Rafelson’s flat objective camera, distances us from the characters instead of pulling us into their plight. Jack Nicholson, who was perfect as a noir-style detective in Chinatown seven years earlier, is miscast here: He’s too smirky-savvy to convince as that other noir trope, the lovestruck chump. Jessica Lange is saddled with an underwritten character who lacks clear motivation, but within a year, she'd finally get the chance to demonstrate her powerful range in Frances and Tootsie. This version is mainly famous for including semi-explicit sex scenes from the novel that the 1946 version couldn’t, but Garfield’s slow eyeing of Turner in her white playsuit is still hotter than Nicholson and Lange’s quick-cut quasi kink. The real reason to watch this version is Anjelica Huston, who’s electric and genuinely erotic in her one scene, in and out of clothes. When she pulls out of town in a run-down circus caravan, we want to go on the road with her.

4. Le Dernier tournant (aka The Last Turn, 1939) starring Corinne Luchaire and Fernand Gravey.

It’s fascinating to see what French filmmakers could do with American pulp fiction, five years before the noir style would be crystallized in Hollywood films like 1944’s Double Indemnity (another Cain adaptation) and a full seven years before French critics would coin the term "film noir". With no previous adaptations to diverge from or wink at, this film quotes more liberally from the novel than the other versions, as when the wife begs Fernand Gravey’s broody, turtlenecked gambler for help to leave her “greasy” (“graisseux”) husband—knowing that the 18-year-old actress, Corinne Luchaire, would make only three more films before dying of tuberculosis adds even more poignancy to her pleas. More than in the novel or the later films, this version sets up a triad, making the affable cuckolded husband (Michel Simon) an equal player from the outset; when his cat dies, Simon mourns his pet and blames himself, which underscores his innocence and reminds us of the sadness and loss that accompany death, despite the sexy trappings of the story.

Best of all, most of the legal mumbo-jumbo that slows down the second half of both American movies is condensed here; gendarmes and insurance investigators convene at the scene of the crime instead of in stuffy offices and courtrooms, and the nighttime setting is full of canted angles and noir shadows. Like Ossessione, Le Dernier tournant was almost lost to history: In 1940 after the Occupation of France, Nazi censors banned the film because the director, Pierre Chenal, was Jewish; after WWII, it was censored again because some of its participants had been Nazi sympathizers. A few prints survived, and you can watch the film online with English subtitles.

Have you seen any of the adaptations of The Postman Always Rings Twice? Which is your favourite?