Premiering at the 53rd Cannes Film Festival, Lars von Trier's Dancer in the Dark became one of the most discussed films of 2000. At the end of the festivities, von Trier would walk away with the Palme D'Or while his leading lady, Icelandic music artist Björk, won the Best Actress prize. It's unusual for any Cannes competition title to win more than one award from the main jury, but sometimes it's impossible to deny a performance's magnificence. Such was the case in 2000. As the musical hit theaters critics worldwide began to chime in and the praise for Björk's achievement became more mountainous. Even some who objected to von Trier's experiment had words of adoration for its star.

It's fair to say that Björk's performance in Dancer in the Dark was one of the most acclaimed acting achievements of 2000. Nonetheless, when Oscar nomination morning arrived, she wasn't among the Best Actress nominees…

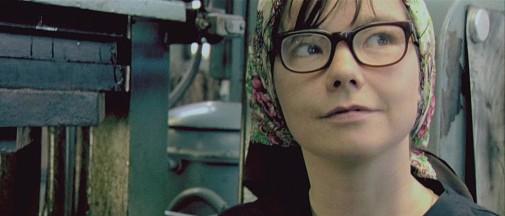

Shot with rudimentary digital cameras and an aesthetic derived from the Dogme 95 movement, Dancer in the Dark is a postmodern musical about Selma, a musical-loving Czech immigrant living in 1960s America with her son. Splitting her days between work at a kitchen sinks factory and rehearsals for a community theater staging of The Sound of Music, she struggles with vision problems. Unbeknownst to friends, family, doctors, and employers, Selma's sight has deteriorated to the point that she's virtually blind. Desperate to make sure that her child won't suffer the same malady, she's been saving money to pay for a surgery that will hopefully salvage the kid's eyes before they stop working altogether.

The situation is already prone to a certain level of exploitation, a portrayal of working-class misery whose toothy mouth waters at the idea of more suffering. Such ill fates are quick to materialize when Selma confides the reality of her condition to Bill, a local policeman and her landlord. One day, after a factory accident leaves her without a job, the protagonist discovers the surgery money's missing, stolen by the only man who knew her secret. The ensuing confrontation has a bloody end, sealing Selma's fate. The woman's stubbornness, her unwillingness to reveal what she knows, only precipitates the doomed finale of this tragedy.

On paper, it's difficult not to read a monstrous amount of misogyny in the scenario. After all, Dancer in the Dark is the last entry in the Golden Hearts trilogy, a collection of films where Lars von Trier immortalized the stories of naïve women, saintly predisposed to suffer and sacrifice themselves. Still, the best films from the director's oeuvre circumvent the dilemma of women-hating diatribe through casts ready to set the screen ablaze in fiery discord. Like Emily Watson had done in Breaking the Waves and Nicole Kidman would do in Dogville, Björk often comes off as a combative element fighting the film's vision of Selma from within.

Even ignoring the merits of the performance proper, Björk's casting is a feat of genius that sets Dancer in the Dark in the path of success. To put it bluntly, the Icelandic actress is not of this world. There's an alien allure to her, essential and fascinatingly odd. The sheer energy she brings to the film infects the trite mechanisms of the plot, making Selma's self-annihilating decisions feel more authentic than convoluted. Better yet, Björk's presence is characterized by joyful effervescence, an ethereal quality that makes Selma's daydreaming feel rooted in truth. No matter what happens to her character, the singer's appearance in front of the camera is enough to contradict the possibility of pornographic misery.

Of course, the performance itself is a wonder of unassuming precision, bullish intensity, explosive feeling. With her vaguely infantile aloofness, Björk's Selma could come off as a witless innocent if the performer didn't ground her character so precisely. Whatever sincere whimsy there is, it exists within the narrative as a canny defense mechanism, a survival strategy. She daydreams as a way to keep her sanity, to face the bleak reality of her existence without flinching or giving up. Regarding her tendency for tragic endings, Selma's willingness to suffer isn't the product of a martyr's obsession. Neither is she motivated by some twisted desire for misery, a masochist's glut for punishment.

Selma's sacrifice is justified by her situation and, through Björk, we get to read the woman's deadly choices as measured tactics. It's just as innately deliberate as the woman's musical reveries. She walks towards doom, not because she's a saint, but because the consequences for not doing so would be even more unbearable to her "golden" heart. Suppose von Trier's text wants to smash the porcelain doll of Selma's being. In that case, Björk's acting courageously attempts to keep the doll's pieces together, to avoid shattering even as the character capitulates to her gallows-bound destiny. This being a tragedy, shattering happens no matter what the actress does to avoid it.

A ball of despair and confusion, anger and disgust, Selma's last non-musical scene with Bill is lacerating to watch. Björk plays the tortured interaction with such helplessness one can't help but feel hot knives stabbing at the heart. As she kills, she's overcome by a deep rage that was hitherto unexplored, and, through all this, Selma is painfully human. Through Björk's bruised take on her character, Lars von Trier cinema becomes that most unexpected of things - an expression of pure empathy. Miraculous is the word for it. Indeed, for a singer, Björk would make for a fantastic silent film actress, so strong is the clarity with which she can illustrate complex sentiment, the masking of it.

During the trial scenes and prison conversations, von Trier often points his camera at her face and lets it fill the frame with electrifying power. I get chills looking at her in such moments, witnessing how this Icelandic marvel proves herself to be a good heir to the mantle of such performers as Falconetti, Nielsen, Gaynor, and so many other queens of the silent silver screen. She swallows down the fear, the realization of impending doom, but doesn't allow all those emotions to overwhelm her face. As someone who's consistently hiding her actual pains, Selma is a character for which overt demonstrativeness is wrong. Only in exact instances does she reveal the fear inside, the animal terror, the paralyzing pain. It's a performance so raw it spews blood when you push on it.

It'd be inexcusable to analyze this performance and not mention how Björk performs the songs she wrote for Dancer in the Dark, so here we go. The first outright musical number takes 40 minutes to arrive. When it does, a cheery tune sang to the sound of an industrial cacophony. It's both a breath of fresh air and a presage of misery. Singing euphoria translates, on-screen, to escapist derangement, as beautiful as it is cutting. Gradually, watching how the character seems to become lighter when dreaming music, the audience is seduced into becoming just like Selma. We, too, need the mercy of the musical fantasy to sustain us through this. Without the songs, Dancer in the Dark would be unbearable.

Björk reflects that dynamic in her committed performance of the tunes, giving in to the extremes of emotion, be it feverish joy or serenity in the face of death. Like Liza Minelli at the end of Cabaret, Björk sings "I've Seen It All" as an act of joyful self-delusion, a desperate bout of self-affirmation. Narratively and inside the character's mind, she's attempting to convince a friend that she's okay. More importantly, though, Selma's trying to convince herself that everything is going to be alright. It's not. Later, when this escapist mechanism falters, and the truth is too screeching to ignore, the pain is excruciating. Alone in her cell, she sobs her way through The Sound of Music's "My Favorite Things," and we break apart. The actress captures her audience completely, holds them close, and destroys them through a performance that marries the necessary artifice of musicals with a grisly sense of realism.

In the research and writing of this piece, I read many reviews of Dancer in the Dark, both from its original release and more recent years. I saw some describe it as the continuation of a tradition of classic tragedy updated for new cinematic languages, as an attack on the musical genre that equates escapism to an idiot's delight, as a melodramatic triumph, a nihilistic failure. While I remain steadfast in my love for the film, it's a complicated affection. I find myself agreeing and disagreeing with many critics and academics on both sides of the matter. The internal struggles of the production, its behind-the-scenes drama, further complicate those feelings.

Filming Dancer in the Dark was not a fun experience for Björk, the star clashing with her director tremendously. Apart from some experimental work, she hasn't acted on film ever since, with Robert Eggers' The Northman marking her big-screen return. Catherine Deneuve has spoken in interviews about how painful the experience was for her Icelandic colleague while von Trier has gilded the lily of their conflict in a voracious fashion. According to him, she'd greet the director every day by spitting on him. Dancer in the Dark is thus a painful film birthed from a painful process. These tensions mark the final project like a web of raised scars.

One can often feel Lars von Trier's love for misery and Björk's ethereal jubilation pulling the film in different directions. The messy struggle they generate ends up creating a vicious sort of barbed equilibrium, a fragile balance, essential to Dancer in the Dark's success. At every step, one feels like the film is challenging itself, arguing between form and performance, story and music. That challenge extends beyond the screen, reverberating in the audience's experience. Take Björk away, and Dancer in the Dark falls apart, irreparably so. In the end, she's more than just a performer and songwriter. Alongside her director, she's the ultimate author of this work of art—no wonder the Cannes jury saw fit to ignore tradition and gave her a prize.

After that victory in the Croisette, Björk got a surprising amount of awards season support considering the punitive, wildly abrasive nature of her film. The highest-profile honor came from the Golden Globes, who perplexingly characterized Dancer in the Dark as a drama and nominated Björk in the corresponding Best Actress category. Across critics' prizes, she often got runner-up mentions, while the National Board of Review awarded her a special honor for Outstanding Dramatic Music Performance. In the end, though, AMPAS kept the Icelandic goddess away from their Best Actress lineup.

The nominees were Joan Allen in The Contender, Juliette Binoche in Chocolat, Ellen Burstyn in Requiem for a Dream, Laura Linney in You Can Count On Me, and Julia Roberts in Erin Brockovich. The latter would take the trophy, while Binoche and Allen were the most vulnerable in the lineup. It's easy to imagine a scenario where Björk takes either of their spots. Still, von Trier's songstress was nominated for an Oscar in the Best Song category. Because of that, we got to admire her red-carpet exuberance as she dressed like a swan, one of the most memorable looks in Academy Awards history. Silver linings aside, Björk deserved to be in the Best Actress lineup.

Dancer in the Dark is currently available to stream or to rent from the usual services.