Before we say goodbye to 2000 and move forward to the next Smackdown year, 1946, I'd like to take a look at the Best Costume Design Oscar race. Take it as a digestif to our coverage. In any case, this specific lineup offers a remarkably comprehensive overview of some of the category's favorite elements and most glaring blind spots. As always, period work dominates, though there's also space for fantasy and contemporary narratives, intersections of fashion and costume, as well as a non-English-language movie. The nominees were…

- Anthony Powell, 102 Dalmatians

- Rita Ryack, How the Grinch Stole Christmas

- Jacqueline West, Quills

- Janty Yates, Gladiator ★

- Tim Yip, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

First up, let's look at the period films and, more specifically, our victor. Janty Yates received her only Academy Award for designing the costumes for Ridley Scott's Best Picture champion. Evoking Roman imperial fashions and battle-ready armor, the Gladiator wardrobe nods towards history without copying it. In the tradition of old Sword and Sandal epics, the movie's only interested in fact up to a point. More critical than verisimilitude, spectacle and operatic storytelling are the dominant forces that define the picture's look.

As the only woman with a sizeable role in this sausage fest, Connie Nielsen gets to model some of the most glamourous and anachronistic ensembles. Eschewing total realism, Yates draped gorgeous Indian silks over the actress, painting her in inaccurately bright hues and expanses of shiny machine embroidery. In some scenes, she even sports ornamental corsets that would be more at home in a 1990s runway than in an Ancient Roman court. Still, the attire suggests an old world lost to time. It dazzles and seduces.

As the only woman with a sizeable role in this sausage fest, Connie Nielsen gets to model some of the most glamourous and anachronistic ensembles. Eschewing total realism, Yates draped gorgeous Indian silks over the actress, painting her in inaccurately bright hues and expanses of shiny machine embroidery. In some scenes, she even sports ornamental corsets that would be more at home in a 1990s runway than in an Ancient Roman court. Still, the attire suggests an old world lost to time. It dazzles and seduces.

After her, the flick's most outlandish costumes belong to the rest of the royal family. While Richard Harris' aged emperor gets little screen-time, his armor is a beautiful example of non-functional military garb. His on-screen son's wardrobe takes that stylistic logic to extremes. As Commodus, Joaquin Phoenix walks around in the finest and most absurd examples of Roman opulence, a gold-plated peacock with a psychotic edge. My favorite costume in the entire film is his last ensemble, a grotesque armor in blinding white. It's the character's hubris materialized as well as a magnificent canvas to showcase spilled blood.

No analysis of the film's wardrobe, even one as short as this one, would be complete without mentioning its star's outfits. Across 12 armor configurations, Russell Crowe's Maximus goes from glorious general to downtrodden slave warrior, cannon-fodder for the arena, and, then, a hero of carnage. Notice that his main breastplate evolves throughout the narrative. With each victory, Maximus adds a new silver embellishment, marks of the life he's lost to Commodus's tyranny. At first, the illustrations were subtle, like horses or olive trees. By the end, he wears the figures of his slain wife and child. This particular detail was the actor's idea, and Yates ran with it.

When designing the costumes for Philip Kaufman's Quills, Jacqueline West needed to keep a steadier foot on the side of historicism, abandoning some of the fantasy Yates indulged in. Despite some chaotic writing, this story focuses on the Marquis de Sade's fate during the aftermath of the French Revolution. The flick opens with a bloody prologue wherein aristocrats wait their turn on the guillotine, looking like faded specters of former splendorous Rococo styles. After this prologue, the fashions evolve to the Neoclassical lines of Napoleon's reign, high waists and column-like skirts on women, starched collars, and tight breeches on the men.

The Marquis, however, doesn't evolve with the times. His outfit is a relic from the past, its dusty color conferring the man with the vague threat and romantic melancholy of a ghostly apparition. Indeed, while his soiled shirts and ratted frockcoats aren't too luxurious, Geoffrey Rush's primary costume is this cinematic wardrobe's highlight. When paper is taken from him, the maddened author writes on his clothes. Blood's his ink, resulting in a haunting sight of the artist becoming one with his sordid art. Future Oscar-winner Michael O'Connor was one of the assistants tasked with resolving the placement of the writings along the suit's body.

While I like a lot of this wardrobe's creations, the general sense of washed-out elegance, bleached glory, corroded nobility, some choices are irksome. On the one hand, having Kate Winslet walk around with her stays worn on the outside makes sense as a signifier of her latent desire, sexual curiosity. However, it also comes off as a bit too heavy-handed and too visually discordant. The silhouette produced is terribly démodé for the period, and even her character's elderly mother is more up-to-date. Nonetheless, the craftsmanship is remarkable.

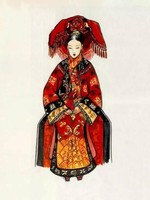

The final period piece in contention was Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, one of the most-nominated non-English language films in Oscar history. Excellent designer Tim Yip, also known as Timmy Yip, was the man in charge of both the sets and the costumes, conceiving a very coordinated and unified look for the production. Rather than copying the traditional model of the wuxia, Lee and his collaborators aimed at something more off-beat and deliberately ponderous, an action period drama that's as preoccupied with melodramatic longing as with the clash of bodies.

Yip's designs reflect the recalibrated aims of this wuxia pastiche, starting from the historical period in which he situates the story. While most classic films in the genre, like King Hu's masterpieces, harken back to ancient times, usually situating the stories somewhere in the Tang dynasty, Yip makes Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon into a tale on the edge of modernity. He reproduces the styles of the Qing dynasty while simplifying some of the heavy ornament, preferring soft dyes and painted silks over more saturated textiles.

Looking at Yip's creations for the stage, one can better appreciate his disciplined contention. The designer's holding himself back, adapting to the cinematic milieu of a director obsessed with stories of romantic repression. The simplicity makes Li Mu Bai and Jen's fight into a ballet of floating ghost flying across the verdant bamboo forest. This also means any deviation hits with doubled force. Please think back to the shocking power of Zhang Ziyi's nuptial reds or the sandy patterns worn by her character's paramour. Speaking of which, the script may not make this clear, but Tim Yip's costumes announce that the social taboo of their romance is as tied to ethnicity as to class.

Looking at Yip's creations for the stage, one can better appreciate his disciplined contention. The designer's holding himself back, adapting to the cinematic milieu of a director obsessed with stories of romantic repression. The simplicity makes Li Mu Bai and Jen's fight into a ballet of floating ghost flying across the verdant bamboo forest. This also means any deviation hits with doubled force. Please think back to the shocking power of Zhang Ziyi's nuptial reds or the sandy patterns worn by her character's paramour. Speaking of which, the script may not make this clear, but Tim Yip's costumes announce that the social taboo of their romance is as tied to ethnicity as to class.

I'm not very fond of Ron Howard's telling of How the Grinch Stole Christmas, but I shall try to be charitable in my overview of its costumes. Indeed, Rita Ryack's designs for the Yuletide fantasy are one of its saving graces. Opting for a midcentury aesthetic twisted into kaleidoscopic lunacy, the artist helped create over 400 costumes that took inspiration from Dr. Seuss' original book as well as the 1966 animated short. Part of the challenge was suggesting bodily proportions out of whack with human reality.

The Whos of Whoville are a bit like pears, their bottoms heavy and their heads often ending in pointy coiffures or conical chapeaux. Most of all, Ryack worked with a team of designers to convey a handmade feel to the proceedings, employing techniques from Scandinavian knitwear and other artisanal crafts. The result is a cartoonish look that defies convention and nods at an anarchic sense of balance, curvilinear obsessions, zany decoration. It's both otherworldly and oddly grounded, garish and weirdly sedate too.

While Ryack's designs are never helped by Donald Peterman's absurdly dark and murky cinematography, it feels unfair to criticize a designer's work for the lensing's failures. While the camera's tendency to dull brilliant whites, render greens muddy, and reds as bruised maroons hides a lot of the sartorial glory, some fashions survive. In collaboration with the makeup department, the artist created the Yak fur bodysuit that helped Carrey turn into the Grinch. There's also the case of Christine Baranski's campy holiday-themed ensembles, which are especially fun. Sure, she looks like a Christmas-obsessed drag queen, but that's a win in my book.

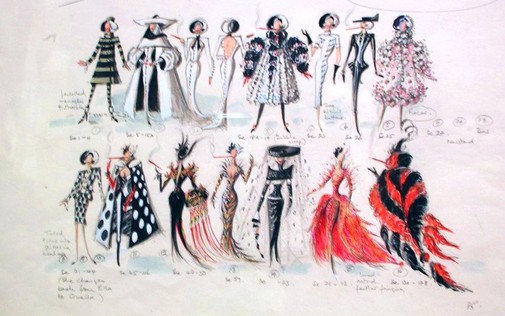

Finally, we have Anthony Powell's second coming as the designer of Cruella De Vil's magnificently malevolent menagerie of furry haute-couture. Utterly untethered from the plot skeleton of the 1956 book and 1963 cartoon, 102 Dalmatians is freer to experiment with the character of Cruella, pushing her to hysterical extremes. Starting the film as a reformed madwoman, Glenn Close parades in 60s inspired dresses and coats cut to look like a nun's habit. Her saintliness is so sugary as to become revolting. Her goodness isn't long for this world, though.

As Big Ben strikes its imperious gong, the evil impulses resurface, and Powell illustrates the transformation through the metamorphosis of a houndstooth suit. Plain, black-and-white wool becomes sparkly. A shabby blouse gains shimmering sequins, pearls, and golden coins turn into a necklace of spikes. More menacingly, the rounded shoulders of the conservative suit explode into a Pagoda style while the white gloves turn black and grow claws. As a kid, I was obsessed by this stylish violation of Cruella's reformed personality, her character arc expressed in reality-bending costuming. I guess I can credit Powell with planting the seeds for my love of costume design.

Better yet, that's just the peak of the fashion iceberg. 102 Dalmatians includes a rich panoply of other sartorial dreams, be it a fiery evening gown, a Chinese Dragon suit, or the deception of a polka-dotted cape lined in zebra fur (faux, of course). And that's just Close's wardrobe. Going beyond Cruella, one finds a runway show that's as much movie magic as a parody of 90s trends, a French furrier with a leopard's head codpiece, and even a sweet ingenue crowned with butterfly clips. Powell gets my vote out of the five nominees, even as I recognize Yates wasn't an unworthy victor.

Truth be told, 2000 was a prosperous cinematic year when it came to great costume design. One doesn't need to stray from the Oscar eligible titles to come up with five films just as deserving of the nominations as these. Take a look:

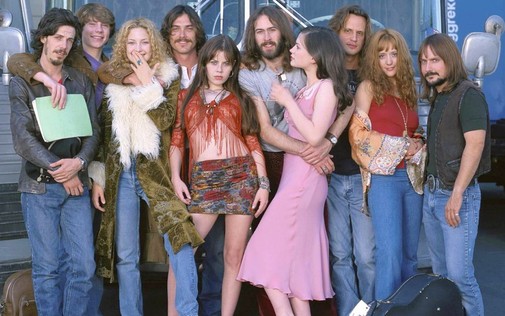

ALMOST FAMOUS

Costumes designed by Betsy Heimann

Yes, Penny Lane's shearling coat is perfect, maybe one of the best and most memorable coats ever put on film. However, we shouldn't minimize Besty Heimann's achievement to just one piece of clothing. Full of period detail, cultural signifiers, and dreamy rock'n'roll glamour, the costumes of Almost Famous are a vital part of the immersive spell Cameron Crowe casts over the audience. We feel transported to the past, to nostalgic memory, partly because of how materially credible this historical evocation ends up being.

THE CELL

Costumes designed by April Napier and Eiko Ishioka

Ishioka's first collaboration with director Tarsem Singh found her creating the hellish wonderland inside a serial killer's head. Pulling from religious, anatomical, and fetishistic imagery, the Japanese designer constructed such awe-inspiring sights, the spectator's sure to have their own dreams infected by Ishioka's visions. Furthermore, April Napier's rendering of the mundane world sets the stage for the impossible variations of the unconscious mind, hinting at motifs that are then exploded outwards in the film's many fantasy sequences.

ERIN BROCKOVICH

Costumes designed by Jeffrey Kurland

One of the best designers working in film, Jeffrey Kurland rarely draws attention to his craft. Whether clothing Woody Allen period pieces or Christopher Nolan's oneiric epics, the designer's main interest always seems to be in world-building and character-based costuming. Erin Brockovich is a perfect example of the latter, seeing as so much of the lead's abrasive presence comes from her putatively inappropriate attire. What could have been cartoonish, even objectifying, in the hands of other designers, is here grounded and naturalistic. Kurland invites us to know this woman, not to gawk at her.

THE HOUSE OF MIRTH

Costumes designed by Monica Howe

The films of Terence Davies draw much of their power from the fragile tonalities the cineaste creates. Halfway between amber-crystalized reminiscence and cruel phantasmagoria, his evocations of the past feel both ethereal and tangible. As we examine the tragic tale of an Edwardian lady, her world is brought to life in exquisite detail. We buy into the unsaid codes of conduct by which her life is destroyed precisely because the reality from which they sprout is so fully realized. At the same time, mournful veils, gauzy flounces, and apparitions of blood-red eveningwear indicate a more theatrical understanding of social mores.

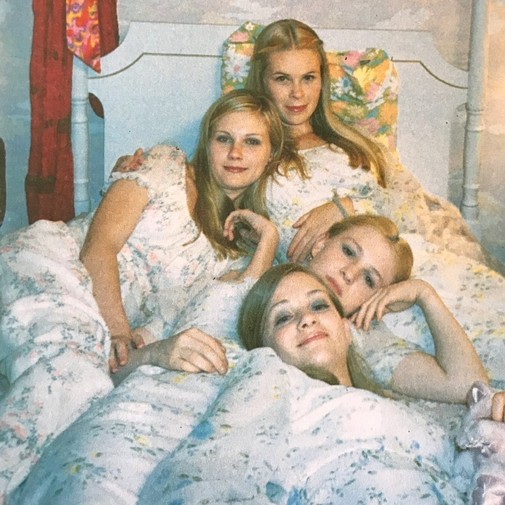

THE VIRGIN SUICIDES

Costumes designed by Nancy Steiner

Sofia Coppola's films are wonderfully costumed, and her debut, The Virgin Suicides, is no different. Pulling small details directly from Jeffrey Eugenides' book, Nancy Steiner produced a vision of late-70s youth that wavers between undefined idealizations and unvarnished truth. The Lisbon sisters are both projections and people, dreams and flesh. With their modest prom dresses in variations of washed-out florals, they look like the flowers that adorned Hamlet's Ophelia as she sank. They're beautiful, fragile, and radiantly alive, but only for a moment. After their brief time in the sun, they all shall sink into premature graves.

I've examined ten cinematic wardrobes, and still, there are many other achievements from 2000 cinema that deserve recognition. There's the fun sexiness of Charlie's Angels and Miss Congeniality, the painterly abstraction of Goya in Bordeaux, the comedic caricature of Best in Show, the poisonous glamour of Mussolini's Italy in Up at the Villa and Malena, the Great Depression beauty of The Legend of Bagger Vance and O Brother, Where Art Thou? and so much more. What are your favorite film wardrobes from 2000?