By Glenn Dunks

Jia Zhangke is one of my favorite working directors. His dramatic features about contemporary Chinese life in the face of widespread modern upheavals are frequently works of masterful elegance. As rich in political and social context as they are well-acted and beautifully crafted. His works of non-fiction present something dramatically quieter; naturally a bit harder to engage with; like his 2007 garment factory doc Useless, modest and observational.

Jia Zhangke is one of my favorite working directors. His dramatic features about contemporary Chinese life in the face of widespread modern upheavals are frequently works of masterful elegance. As rich in political and social context as they are well-acted and beautifully crafted. His works of non-fiction present something dramatically quieter; naturally a bit harder to engage with; like his 2007 garment factory doc Useless, modest and observational.

In many ways, his latest film shares that lack of narrative flare. Something that no doubt added to its quieter festival reception in 2020. But Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue nonetheless has something of a keener eye and so, even when the importance of its subjects may be lost on a western audience, it finds burrows of ideas that flourish through a veil of unexpected stylistic choices.

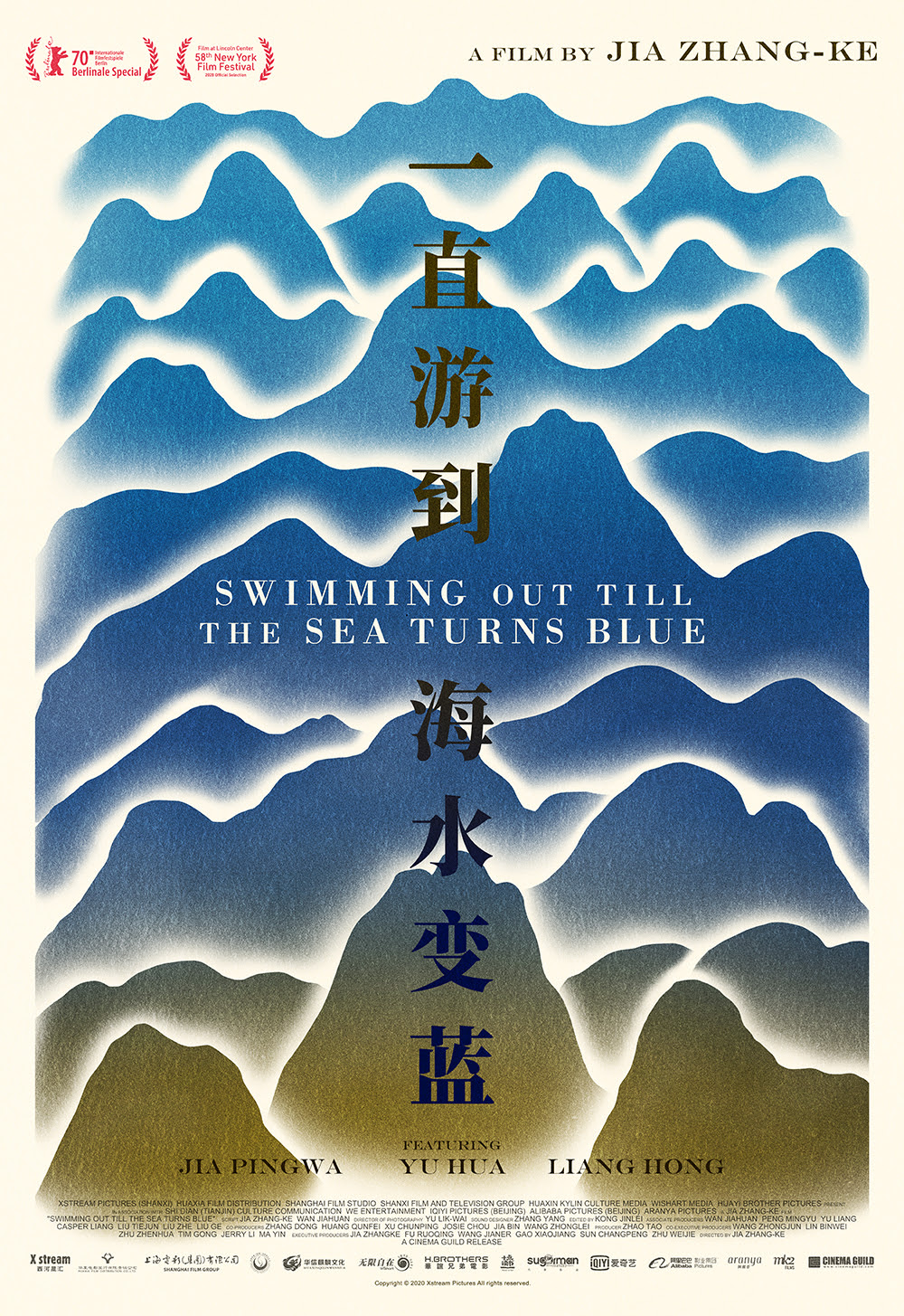

His fourth feature documentary after Dong about painter Liu Xiaodong, the aforementioned Useless, and I Wish I Knew, Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue is an ode of sorts to artists. The writers whose ideas and messages arose out of the same Shangxi province as the director did, Jia Family Village (no relation to Jia’s family). Jia Pingwa, Yu Hua, and Liang Hong all share stories from social revolution of the 1950s to political revolution of the 1980s, appearing out these turbulent times to write works that spoke to a emerging Chinese demographic. Additionally, the work of the late Ma Feng is spoken of, their legacy one of influence as much as talent.

Compared to dramatic films like Still Life, A Touch of Sin, Ash is Purest White and Mountains May Depart, it’s perhaps easy to underestimate the formal rigour that Jia brings to Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue. Considering the film is little more than a stringed-together collection of talking head interviews, Jia and his collaborators make a lot of subtle, complex choices that reap major benefits. This is particularly so because, at 112 minutes, many will find attention spans tested by its simple conversational set-up.

Nelson Lik-wai Yu, whose work has been so important to Jia’s earlier films, yet again makes magic. Here he turns one-on-one discussions into unexpectedly stylised treats. He finds small ways of framing and shooting his subjects that elevate the material in ways that—as interesting as the content often is—the film sorely needed. These discussions with these titans of Chinese literature are interspersed with images of street scenes and traditional village life (making dumplings, a parade of floating candles down the Yellow River) that highlight the massive changes in the country’s society as well as those that have remained relatively in fact. Likewise, Zhang Jia’s editing and Zhang Yang’s sound design add their own intricate minor keys that combine to allow these interviewees to be spotlighted and not overlooked. The former particularly in its setup of 18 chapters (some more enigmatically titled than others), a nod to the authorly histories at its core.

The stories these authors tell, particularly Liang and Yu in its admittedly more engaging (and funnier) second half, are those of a changing China. It’s hardly surprising that Jia Zhangke was interested in telling their stories. The way Liang tells of a family that could only afford to send one child to school, resulting in a wealth and class disparity that is navigated just as much through glances as it is words.

A film like Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue feels genuinely rare. A filmmaker allowed the opportunity to extol the virtues of his homeland heroes, examining how China’s roots in the provinces has influenced a generation outside of it. Jia Zhangke is a director who seems quite happy to leave big dramatic arcs to his fictional films, leaving a documentary like this one to simmer in those authentic, familiar atmospheres within which he too grew up. It’s a lovely film, one that requires patience, but which rewards viewers with keen insights to a world they likely never knew.

Release: Opens today in LA and NY theatres through Cinema Guild. It will presumably travel from there through major city arthouses with strong Chinese demographics.

Oscar chances: Unlikely. The Academy at large have yet to recognise his films despite the admiration and even critics awards. I can't imagine this one will change that.