by Brent Calderwood

Alida Valli, who was born 100 years ago today in Pola, Italy (now part of Croatia), became a legend of Italian cinema in classics ranging in style from Luchino Visconti’s operatic epic Senso to Dario Argento’s supernatural slasher Suspiria. In a career that spanned 68 years, international directors were repeatedly drawn to her dark, inscrutable beauty and haunted green eyes. She's still admired by film lovers worldwide for three noir-tinged movies she made while abroad: The Third Man opposite Orson Welles (where she gets one of the most famous screen exits in history), Alfred Hitchcock’s The Paradine Case, and the French horror film Eyes Without a Face.

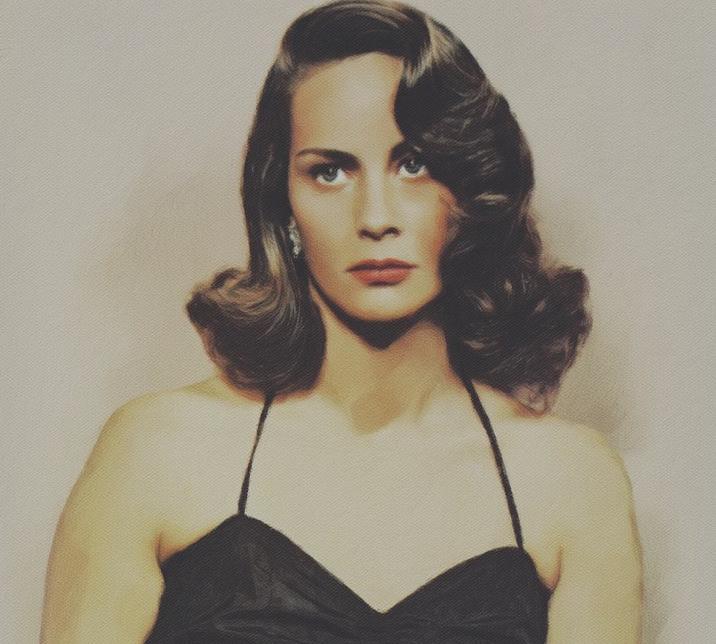

In 1947, producer David O. Selznick invited Valli to Hollywood, hoping to repeat the success he’d had with two of his other European “discoveries,” Ingrid Bergman and Vivien Leigh. He gave her the full star treatment, even briefly abbreviating her name to the one-word “Valli” à la “Garbo” and having Hitchcock helm her first American picture...

in a publicity still for "The Paradine Case". Don't we all have portraits of ourseves on our headboards?

in a publicity still for "The Paradine Case". Don't we all have portraits of ourseves on our headboards?

The Paradine Case, though, ended up being more star-crossed than star-making, due in part to Selznick’s Benzedrine-fueled overnight script rewrites and his penchant for cutting and re-editing the Master of Suspense’s carefully staged single takes. (The stifled auteur channeled his frustration into his future work, notably using Selznick as the visual inspiration for the nocturnal, saw-wielding philanderer played by Raymond Burr in Rear Window.)

Today, The Paradine Case is still one of Hitchcock’s lesser-known American films, but when it is remembered, it’s usually for the moments with Valli—which is pretty impressive considering her costars were Gregory Peck, Charles Laughton, Ethel Barrymore (in an Oscar-nominated supporting role), and another new Selznick contract player, Louis Jourdan. In fact, Valli is the focal point of the best shot in the film, one that still shows up in Hitchcock docs and highlight reels.

Accused of murdering her wealthy husband, Valli as Mrs. Paradine sits frozen in the prisoner’s dock of London’s Old Bailey courtroom, surrounded by jurors and white-wigged barristers; as the young valetplayed by Jourdan passes behind her to the witness stand, Valli’s face is an icy, imperious mask that can’t quite disguise her snarl of fear and lust. As Hitchcock told Francois Truffaut about the scene, “We wanted to give the impression that she senses his presence…as if she could smell him.”

Since the dynamic deep-focus effect the director wanted wasn’t possible with 1947 lenses, Hitchcock concocted one of his most masterful process shots, with help from cameraman Lee Garmes, whose name was by then already a byword for the kind of chiaroscuro spotlighting favored by Marlene Dietrich and other Hollywood glamour goddesses. First, the camera was placed inside the dock with wooden guardrails and prison guards in the foreground as Jourdan walked through the crowded room; next, the same film was projected onto a screen while Valli, seated alone on a stool in front of the camera, was turned counterclockwise and pulled out of the frame. The result is a seamless take that heightens our anticipationabout what this gentleman’s gentleman will reveal regarding his intimate history with both his mistress and his former master.

a famous shot from "The Third Man"

a famous shot from "The Third Man"

Valli has some of the best lines in The Paradine Case and delivers them with convincing venom, like when she warns Peck, her besotted and very non-Atticus Finch attorney, “You are not to destroy him—if you do, I shall hate you as I have never hated a man.” She got more to sink her teeth into with The Third Man (1949) playing Anna Schmidt, a Czech refugee in war-torn Vienna. Again surrounded on all sides by men who control her fate—British, Soviet, French, and American soldiers and police—she risks deportation rather than provide information about her boyfriend played by Orson Welles. Valli owns the subjective center of most of the scenes she’s in, whether walking through graveyards, sparring with Joseph Cotten, or alone in her crumbling apartment and crying beautifully under Robert Krasker’s Oscar-winning cinematography. Only Welles holds our attention more intensely.

Throughout Valli’s most acclaimed films, all directed and lensed by exquisite visual storytellers, it’s the images that are most often talked about. In the iconic final shot of The Third Man, Valli walks resolutely through Vienna’s Central Cemetery. At first barely discernible in the distance, she heads straight towards the camera, blanking Cotten, our ostensible American hero, as Anton Karas’s zither score plays her wryly off the screen. In that moment, she takes back the power that police, soldiers, and suitors have all tried to strip from her and, to my mind anyway, comes away being the true hero of the film. (To Selznick’s credit, he supported coproducer Alexander Korda and director Carol Reed in adding this downbeat ending despite the author Graham Greene’s misgivings—a change that Greene realized was “triumphantly right” when he saw the finished film.)

in "Senso"

in "Senso" in "Suspiria"

in "Suspiria"

After her stint in Hollywood and into her early eighties, Valli used her maturing allure in service to other virtuosic auteurs, often in increasingly dark parts. In Visconti’s Senso (1954), she’s the top-billed star, and though she’s again betrayed by a lover—this time it’s Farley Granger in form-fitting soldier duds—now she’s a powerful countess who gets revenge. In Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage, 1960), she drives around Paris looking for beautiful young women to abduct. In another classic horror film, Suspiria (1977), Valli plays a beyond-stern head instructor at a German ballet school, with assistance from Joan Bennett, a fellow veteran of ’40s femme fatale roles. The film drips with rich, jewel-toned Technicolor and copious amounts of blood, but Suspiria is too classy (or at least too stylish) to be classified as grande dame guignol; this is “giallo,” a uniquely Italian shocker genre of which Argento was a master.

Viewed alongside the best-known actresses of Hollywood’s Golden Age—stars that Selznick hoped she’d outshine—Valli’s screen persona remains harder to define. In most of her films, her character is an intentional enigma. Gorgeous, languorous, tortured, and maybe a little bit sullen. More composed and guarded than Vivien Leigh; less vulnerable and lit-from-within than Ingrid Bergman. As defiant as Barbara Stanwyck but without the laughs. Something of Joan Crawford’s bone structure, minus the outsized quirks that can make an actress even more famous than her movies. But I never get the sense watching Valli’s films that she wanted to be a one-word star like Garbo anyway, at least not in America; and with over 100 screen roles, she certainly wasn’t interested in early retirement. True, she exudes Garbo’s continental aloofness, but maybe in a way that seems less calculated; maybe in a way that makes us want to keep our distance after all, even while we go on watching in the dark.