by Brent Calderwood

The Kids Are All Right (2010)

The Kids Are All Right (2010)

“Songs are like tattoos.” That’s according to “Blue,” the title track on Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, which turns 50 this month. A half century after Mitchell wrote and recorded those words, it’s clear that Blue has made an indelible mark on the culture. Songwriters from Bob Dylan (“Tangled Up in Blue”) to Prince (“So Blue”) to Taylor Swift (Red) have acknowledged the influence of Blue’s achingly autobiographical lyrics on their own work. Just last year, Rolling Stone declared Blue the third greatest album of all time. And thanks to scores of cover versions over five decades, two of Blue’s torchiest tracks—“A Case of You” and “River”—have become American Songbook standards.

No wonder, then, that filmmakers have frequently tapped into Blue, especially for their characters’ most vulnerable moments. While plenty of ink has been spilled over who the songs on Blue are about (James Taylor, Graham Nash, Leonard Cohen), screenwriters and directors often look deeper, mining the songs for what they are about: love, desire, loss, travel, California, Christmas, and much more.

In honor of the classic album's 50th anniversary, here’s a look at the Top 5 times that songs from Blue appeared in movies…

1. The Kids Are All Right (2010): “All I Want”

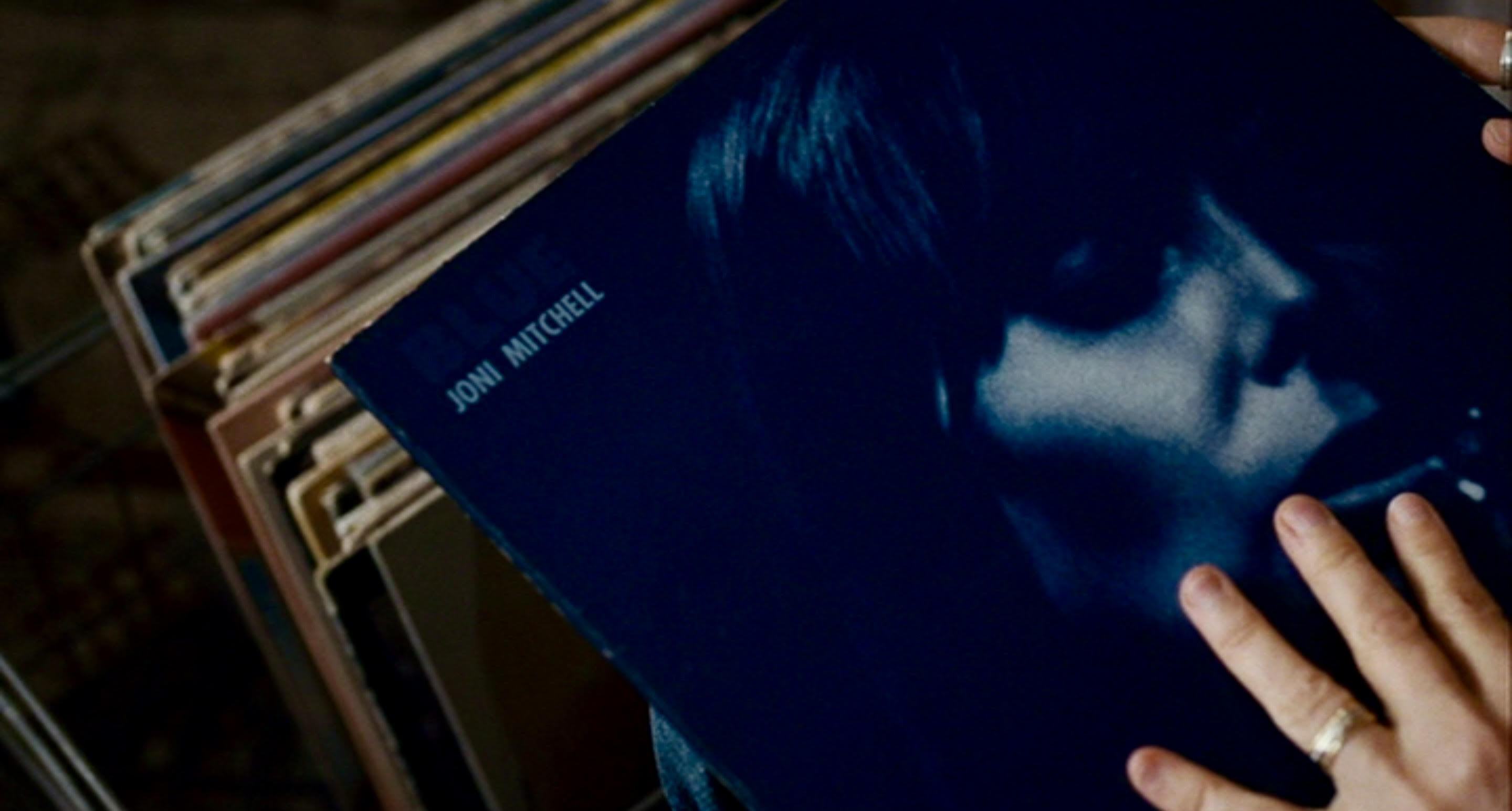

Nic (Annette Bening) is alone on a couch while her wife and their two kids are bonding in the kitchen with Paul (Mark Ruffolo), the kids’ newly discovered, no-longer-anonymous sperm donor dad. Nic is out of her comfort zone in Paul’s hipster pad, but she’s doing her best to be a team player and, well, at least there are record albums to look through (vinyl, of course). The camera, along with Bening’s hand, settles on Joni Mitchell's Blue. You can see Nic’s face soften as she opens the gatefold and reads the lyrics.

By the time everyone’s seated for dinner, Nic is ready to be open to Paul, agreeing with him on the pleasures of rare meat and then complimenting his taste in music. Paul lights up: “You like Joni?” and Nic teases, “No, not really. We just named our daughter after her.” About this scene, Lisa Cholodenko, the film’s director and co-screenwriter, told the Director’s Guild of America: “I let them riff here, not knowing how much I was going to use. But Nic is over the top, really trying to bond with Paul.”

Nic gets so caught up, she launches into an a cappella rendition of the first song on side A of Blue, “All I Want”; she’s joined for a few lines by Paul and then she’s on her own, in tight close-up. With its shifting tempo, multi-octave range, and almost free-associative lyrics, “All I Want” is a challenge even for most pros, so we’re seeing Nic’s willingness to be vulnerable. Relaxed and no longer feeling like the fifth wheel at the party, she accepts Paul’s earlier offer to pour her a glass of wine and steps away to use the bathroom—and that’s when she spots strands of her wife’s long red hair in Paul’s hairbrush and bathtub drain. Only a minute earlier, Nic was singing, “Do you see how you hurt me, baby? And I hurt you too, that’s why we both get so blue.”

Since Cholodenko had a tight budget of $4 million, paying to license a Mitchell song—even without the original recording—was a big financial commitment, but she finally decided no other song would pack the same punch. It was money well spent. The Kids Are All Right went on to be a commercial success and a critical darling, with this being the most singled-out scene. The film also scored a Golden Globe for Bening as Best Actress in a Comedy or Musical, as well as Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Actress, Supporting Actor (Ruffalo), and Original Screenplay.

2. The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019): “Blue”

Forty minutes into this remarkable film, the protagonist, Jimmie (Jimmie Fails), is hitching a ride on the back of a truck driving downhill with the San Francisco Bay Bridge visible in the background. Jimmie is flush with the victory of having moved into a Victorian house in the Fillmore District. It’s a bittersweet victory because, although the Fillmore had once been San Francisco’s thriving postwar Black neighborhood, gentrification has since pushed most of its Black population out of the city or to peripheral areas like Hunters Point, where Jimmie’s best friend Montgomery (Jonathan Majors) lives with his grandfather, played touchingly by Danny Glover.

As the truck reaches a busy intersection, an a cappella choir can be heard singing, “Acid booze and ass, needles guns and grass” (lines Mitchell wrote partly about James Taylor’s heroin addiction, but more generally about the shadow side of post-Woodstock counterculture). In a series of impressionistic shots with intermittent music, Jimmie is skateboarding downhill past cable cars, and then we’re back in Hunters Point where the film began. Now the needle has dropped on Mitchell’s own recording of “Blue.” Five young men Jimmie grew up with stand arguing on the sidewalk, and the combination of Mitchell’s keening vocals with slowed-down close-ups of the men’s faces—at once angry, sad, and beautiful—draws us in and elicits our empathy.

The director and co-screenwriter, Joe Talbot, got the idea for this music cue after he heard the rapper Mac Dre’s “Song 4 U,” which heavily samples “Blue,” played at a friend’s funeral. As Talbot explains on the Blu-ray commentary, “In San Francisco, a lot of people grow up in such close proximity to each other—old hippies that came in the ’60s … and people in Hunters Point that … it does give way to these beautiful crossover moments. As unexpected in some ways as I think it is to put Joni Mitchell over that sequence, it also feels very much from the fabric of San Francisco.”

3. Wild (2014): “California”

It’s day 9 of Cheryl Strayed’s 1,100-mile hike along the Pacific Crest Trail from Southern California to the Oregon-Washington border. Cheryl (the future author of the bestselling memoir Wild as portrayed by Reese Witherspoon, who co-produced this film adaptation) has stepped off the trail for one night to grab a shower and bed and buy proper cooking fuel. We’re still trying to get a sense of who this woman is that we’ll be taking this journey with. What we know so far mainly comes through quick-cut, half-glimpsed memories shown in flashback—Cheryl cheating on her boyfriend, shooting heroin, and criticizing her big-hearted mom (beautifully played by Laura Dern—Witherspoon and Dern were Oscar-nominated for Best Actress and Supporting Actress, respectively).

Now we’re about to head back onto the trail. Cheryl lifts the weather-beaten lid that covers the PCT register (a logbook that tells rangers and fellow hikers who’s ahead of them on the trail). Taking a breath, she signs her name and writes out a quote that flashes across the screen: “Will you take me as I am? Will you?” followed by “California” and then “Joni Mitchell.”

“California”’s lyrics are a perfect fit for this uncertain moment, but it was a wise move to use them without the melody, and not just for financial reasons. “California” is one of the three most upbeat tracks on Blue, featuring Mitchell’s jauntily strummed Appalachian dulcimer and lilting vocals along with backing guitar from her then-boyfriend James Taylor. The song recounts the Canadian-born artist’s travels in France, Greece, and Spain before getting homesick for her adopted state. Between verses and into the outro, she asks California (the place itself, and the lover who may or may not be waiting for her when she gets there): “Will you take me as I am?” In one repetition she adds, “Will you take me as I am—strung out on another man?” It’s a request for acceptance, and maybe a bit of a warning.

Seeing these lyrics onscreen resonates most strongly for viewers who know the whole song. In addition to echoing Wild’s Golden State setting and references to heartache and addiction, “California” is also a life-on-the-road narrative—a genre that still privileges male writers; a woman singing about lovers in multiple countries in 1971 risked (and got) slut-shaming from male rock journalists, and a woman hiking alone on the PCT in 1995 was risking physical danger (a tension that runs through the film). But even if you don’t know all this, the question “Will you take me as I am?” still holds power as an invitation and a challenge to the viewer. Will we accept Witherspoon’s character as she is, imperfect and alone in California? Will we? Those who answer “yes” will be rewarded with a sometimes uncomfortable and ultimately moving film-watching experience. Those who answer “no” should consider taking a hike.

4. Love Actually (2003): “River”

Karen (Emma Thompson) and Harry (Alan Rickman) are listening to Christmas music in their family room. We’re 44 minutes into a film chock-full of intersecting storylines and gotcha moments, and it’s the first time we’re seeing that these characters are married. Karen is dutifully wrapping their children’s presents on the floor while Harry glowers in an armchair. Mitchell’s intro to “River” drifts in on the stereo—a minor-key piano riff on “Jingle Bells” followed by clear, lonesome vocals (“They’re puttin’ up reindeer and singin’ songs of joy and peace … I wish I had a river I could skate away on”). Harry grouses, “I can’t believe you still listen to Joni Mitchell.” Karen winces almost imperceptibly, then puts on the stoic smile she’s worn through most of her previous scenes. “I love her, and true love lasts a lifetime. Joni Mitchell is the woman who taught your cold English wife how to feel.”

This setup gets paid off later in the film, when Harry gives Karen her Christmas present, Mitchell’s 2000 CD Both Sides Now, saying, “To continue your emotional education.” Since Thompson now realizes the gold heart pendant she found in his coat was a Christmas present for someone else, she steals away to the bedroom, puts on the title track of the CD, recorded when Mitchell was in her late fifties, and begins to cry. This is the most remembered and best-reviewed moment in the film—a quiet, truthful scene in an otherwise manic movie. Even viewers who aren’t familiar with Mitchell’s 1969 recording of “Both Sides, Now” will recognize, having heard the young voice on “River,” that we are now in the company of an older, wiser singer—and that helps us understand that Karen’s tears are not just about infidelity, but also about aging, disillusionment, memory, and emotional dislocation.

In the DVD extras, the director-screenwriter Richard Curtis explains that listening to Mitchell gave him the idea for this part of the plot and that Karen embodies his own ethos: “I really don’t know anything I didn’t get from Joni Mitchell….” This—along with Thompson’s pitch-perfect performance—helps explain why even grinches (like me) who don’t like Love Actually still find these two scenes genuinely affecting in spite of ourselves.

5. Truly, Madly, Deeply (1990): “A Case of You”

Thirty-one years after the BBC production Truly, Madly, Deeply became a surprise international art-house hit, “A Case of You” is now one of Mitchell’s best-known songs, with memorable performances across virtually every genre by artists including Prince, Herbie Hancock, Diana Krall, k.d. lang, Brandi Carlile, Rufus Wainwright, Graham Nash, and Connie Champagne (performing as Judy Garland). But back in 1990 when first-time director Anthony Minghella incorporated “A Case of You” into his BAFTA-winning screenplay, this song was a deep cut, and that was sort of the point.

When Juliet Stevenson and Alan Rickman begin singing “A Case of You” to each other with its satisfyingly hooky chorus (“I could drink a case of you, and I would still be on my feet….”), it shows us they share a common history, especially when Stevenson cheekily imitates Mitchell’s soaring mezzo-soprano on the song’s highest high notes (this also shows how closely the song was still associated with its first recording—most subsequent covers would rein in the song’s rangiest sections). The playful intimacy of this singalong leads right into the titular dialogue. Stevenson says, “I love you,” and then they both keep adding adverbs till they wind up with “I really, truly, madly, deeply love you.”

Just as Rickman’s dismissal of Mitchell in Love Actually showed his shutdown-ness, his character’s fondness for “A Case of You” here paints him as a nearly perfect husband—sweet, willing to look silly, and emotionally available. Unfortunately, he’s also an illusion. Truly, Madly, Deeply is about a young widow (Stevenson) who’s visited by her late husband (in dream sequences that blend with reality) until she’s ready to move through her grief and get back on her feet.

If you haven’t seen Truly, Madly, Deeply—or if it’s been a while—I recommend giving it a watch. It’s a pleasure to see these two wonderful actors relatively early in their careers, and it’s also a pleasure to witness one of Mitchell’s best songs already getting props in 1990, early in its journey to eventual classic status.