We're revisiting the 1998 film year in the lead up to the next Supporting Actress Smackdown. As always Nick Taylor will suggest a few alternates to Oscar's ballot.

Unlike my last two companion pieces for 1998, which opened with well-deserved grousing about the meager recognition Velvet Goldmine and Beloved received from audiences and industry professionals alike, I actually feel pretty good about how High Art was received on the indie circuit. No, it didn’t get any notices from Oscar, but five nominations at the Independent Spirit Awards, with Ally Sheedy deservedly winning their Lead Actress prize, is a damn good run for any film, to say nothing of how well its reputation has grown since it debuted. But surely the best thing to come from High Art’s success is giving us Patricia Clarkson, Character Actress Extraordinaire™. Her highwire turn as the perpetually soused, washed-up German actress Greta earned Clarkson a handful of runner-up citations from critics groups who would go on to throw prizes at her for the first half of the ‘00s. The remarkable career that High Art made possible for Clarkson gives her performance a wonderful afterglow, and the fact that it still holds up as one of her best turns makes it even more glorious . . . .

High Art frames Greta as one half of a couple whose relationship is entirely upended by the intrusion of a younger, career-oriented neighbor who shows up out of the blue offering to look at their plumbing. Said neighbor is Syd (Radha Mitchell), an assistant editor at a high-end photography magazine called Frame, who soon discovers that she’s living in the same building as Lucy Berliner (Sheedy, beyond exquisite), a once-famous photographer who went into hiding just as her career started taking off. Lucy lives with her girlfriend Greta, a former Fassbinder axiom whose career imploded as soon as he died. She’s also the subject of a good portion of Lucy’s photographs, notably a series of her floating around underwater. Syd gives Lucy an opportunity to revitalize her career, and in the process the two become romantically involved, leaving Greta to desperately try and cleave to a life she knows has been slipping away from her long before now.

The film is deeply enamored with ideas about art, love, sexuality, celebrity, mercenary ambition, and self destruction, all equally insinuating even if they’re realized with different degrees of success from one sequence to the next. The slinky atmosphere, equally hospitable to gauzy, bohemian apartments and hyper-professional office buildings, is a real asset in breathing life into these concepts, especially by way of Tami Reiker’s cinematography and Shudder to Think’s music. Thankfully, High Art is not the sort of procession that qualifies as an acting showcase via its lack of technical craft. All that being said, the actresses are even more indispensable at endowing these ideas with watchful curiosity, sensuous intrigue, and intimidated ambivalence. Where Sheedy focuses these themes through Lucy’s own negotiation of her relationships, Clarkson bathes everything under a patina of ingratiating humor and bleary, listless desolation.

From the moment she’s introduced, Greta emerges as a woman whose general situation is immediately recognizable but is unexpectedly inscrutable to deeper speculation. It’s not quite Dietrich and Von Sternberg, but Cholodenko, Reiker, Clarkson, and costume designer Vicki Ferrell, who keeps sticking her in red dresses and black leather, turns Greta’s body into a series of sloping lines and bold colors, while giving equal attention to her magnificent face. Her claims on audience interest aren’t just psychological but geometric, even when she’s simply scratching her neck or crawling under her bedcovers.

We first see her snorting heroin from a vial in a restaurant bathroom, only to be immediately interrupted by someone knocking on the stall door. It turns out the woman is an acquaintance whose name Greta is thankfully not asked to remember on the spot. They have a short, genial enough conversation about her recent MacArthur Genius Grant, and the whole time Greta says barely more than a dozen words, shifting her weight between the doorframe and the wall and lolling her neck like she can barely keep her body upright before she simply walks away from the other woman while she’s still talking. She struts back to her and Lucy’s table, where she starts talking shit about this acquaintance.

At one point in their conversation, Lucy says she thought Greta wasn’t gonna bring any drugs tonight, and it’s honestly a solid, thought-provoking laugh line on rewatch. How high was Greta when they walked in? Did she promise she wouldn’t get fucked up while they were out, or did Lucy ask for this? Is Greta always this high? As it turns out, the answer to that last question is an outright, unequivocal yes. Clarkson plays Greta as a catty, faded woman, forever observing her corner of the world through a drug-induced fog. The copious amounts of heroin are so heavily present in her loping gait and slurred speech it’s remarkable she’s awake as often as she is. Then again, it’s not uncommon for Greta to slip in and out of consciousness while making out with Lucy on the couch or slouched in her chair at a diner in the middle of an argument, so perhaps her level of functionality shouldn’t be hyped up too much.

Clarkson underlines this by turning so many of her lines into unintelligible mumbling, making her voice as smeary as her physicality. Entire lines of dialogue are rolled around in her mouth and let out in as few hard syllables as possible, either because Greta can’t be bothered by whoever is talking to her or because she’s too high to get her words out as well as she wants to. It’s amazing how well she and Cholodenko are able to spin this for comedy without hitting the cruel jokiness of something like Sophie’s Choice negging its titular character for mixing up words in English. Surely it helps that Greta’s mordant humor and general disinterest is as impacted in its volume and color as her expressions of annoyance and companionship. Clarkson also refuses to use Greta’s stupor as an excuse not to interact with her co-stars, finding the right postures and facial expressions

But really, the reason Greta works as such a unique personality is that Clarkson’s ability to make her watchable and entertaining never undermines the fundamental sadness that characterizes her arc. Even before Greta was recast as the third woman in a love triangle, her relationship with Lucy was already floating in a state of listless comfort. Greta still cares deeply for Lucy, but you get the sense they’re still together largely because they don’t know anyone else half as well as they know each other. Clarkson plays Greta as pure watercolor, flowing freely from one mood to the next within a worryingly muted pallet, denying the sort of sharp, diagonal bristles and conspicuous backstory a different actress might foreground. There’s an easy interpretation of Greta’s addiction as a pointed, immolating kiss-off to a dead career and a dying relationship, yet Clarkson makes it profoundly difficult to imagine a time where Greta was ever sober, for her sake or anyone else’s. There’s no moralizing in her performance, only the truth of her character's experience.

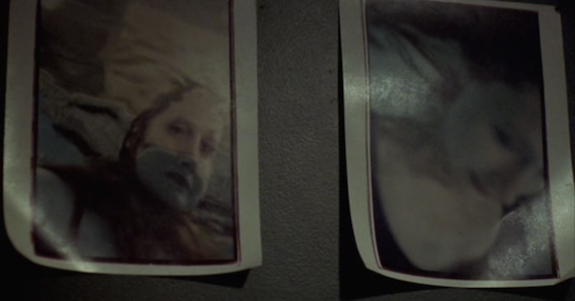

As Syd gets more involved in their lives, Greta shifts from bored amusement at this young woman to jealous disdain. She never rises out of her fog enough to muscle up a real rebuke to Syd and Lucy’s growing attachment, but the fact that her anger rises to whatever limited heights she can muster is enough for us to intuit how much this actually bothers her. The culmination of this comes midway through the film at a party Lucy and Greta are hosting. Syd reveals that not only will Lucy’s photography be on the cover of next month’s Frame, but Syd will be working as Lucy’s editor. Greta’s face gets as wide-eyed as her eyelids can manage, and she shuffles to some other part of the house rather than sticking around to hear more. Soon after this announcement, Greta has to be rescued from drowning after falling asleep in her tub. There’s a harsh irony to this scene, as Greta resembles the underwater portraits of her that made Lucy so famous just as her replacement becomes most imminently obvious. All she can stand to do after she wakes up is cling to Lucy and tell Syd to fuck off.

Afterwards, Greta is in far less of High Art’s second half, sporadically warning Lucy that this bootlicking, psychophantic “teenageer” is simply using her to advance her career. She doesn’t really defend her behavior or try to hype herself up, but she’s more than willing to cast doubt on Syd’s intentions and rebuff Lucy’s pleas that she can’t keep waiting around for Greta to get clean. But Cholodenko also hands her and Lucy the climax of the film, as they say their final goodbyes before Lucy leaves. The overt emotional through-lines and curtailed ambiguity that pervades High Art for its last 30 minutes necessitates Greta be a little more “present” than she has been, but Clarkson makes Greta’s feelings more accessible while maintaining the highwire gauziness that’s defined her throughout. Their spiky, tender rendezvous, which I’m not sure is entirely a reconciliation, is a magnificent send off to both the characters and their performers. But more than anything, I walked away from the film wanting to know what Greta does when she wakes up the next morning, and if anyone is owed credit for that, it's Patricia fucking Clarkson.