We'll be celebrating each of the upcoming Honorary Oscar winners with a few pieces on their career. First up is Danny Glover.

First and foremost, a big fucking congratulations to Danny Glover, whose long, reliable, multi-pronged career is tremendously deserving of the Jean Hersholt Award he will be awarded this year. 2021’s absolutely superb group of Honorary winners makes it all the more fucking absurd these shows aren’t televised, but that’s a whole other tangent. We here at The Film Experience are paying tribute to our favorites among Glover’s remarkable body of work, and when pressed about my favorite of his performances, I immediately went for Charles Burnett’s 1990 feature To Sleep With Anger.

As with Places of the Heart, Glover’s arrival comes just around the fifteen minute mark, by which time we have not only met most of the cast but have gotten acquainted with To Sleep With Anger’s unusual tone...

The one-minute opening tableau depicts a well-dressed black man sitting on a wooden chair, next to a wooden table with a bowl of fruit on it. The walls are painted brown, a portrait hangs on the wall. Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s “Precious Memories” begins to croon, though it’s unclear if the man is listening to it with us or not. Eventually the fruit, the table, and the man are all tickled by ever-growing flames, but they don’t react or suffer damage from it.

The man turns out to be Gideon (Paul Butler), the patriarch of a California family that’s transplanted years and years ago from the rural South. Gideon lives with his wife Suzie (Mary Alice). They are regularly visited by their hardworking son Junior (Carl Lumbly), his pregnant wife Pat (Vonetta McGee) and their teenaged daughter Rhonda (Reina King). They are less regularly visited by their younger son Babe Brother (Richard Brooks) - and his wife Linda (Sheryl Lee Ralph). We never get last names, but we do get an intriguing, rounded texture in the direction and performances, situated between a realist drama and a Biblical parable about unwelcome strangers and simmering family tensions.

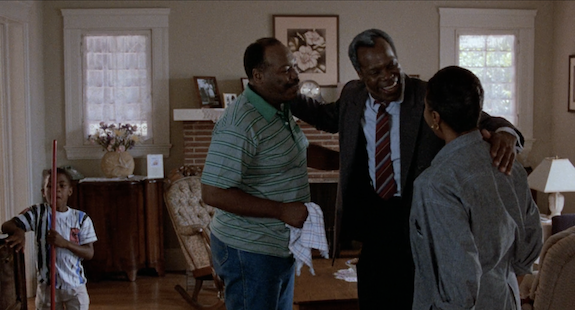

When Harry (Glover), an old friend from the South the family hasn’t seen in 30 years, shows up one morning with graying hair in a suit and tie, they regard him as a welcome reprieve from the anxieties bubbling underneath their peaceful lives. But Burnett takes the time to show Harry darken their doorstep and slip an address book into his pocket, taking a moment to ready himself before ringing their doorbell. There’s an unspoken malevolence to this wordless prelude, casting Harry as both an unwelcome visitor and a demonic spirit that’s invading Gideon and Suzie’s house, and Glover makes this confluence the cornerstone of his performance. Harry is as much a devilish entity as he is a flesh-and-blood man, and To Sleep With Anger lets us wonder which of these realities would be worse for his host family to sit with.

Harry boisterously embraces his friends as soon as he crosses the threshold of their house, only to seize up when Sunny accidentally brushes him with a broom. It’s bad luck, he says, and he takes the time to spit on the bristles and throw salt over his shoulders before he asks for a favor. When he bashfully asks to rest his feet for a spell, Glover communicates to the audience that he’s asking permission from his unsuspecting hosts to inflect the rest of the film’s indignities onto them. Gideon and Suzie tell him he can stay as long as he wishes, and from there the scene almost immediately fades to black as Harry’s new life begins.

Harry starts having one-on-one encounters with the family and friends of his new hosts. Burnett’s script and Nancy Richardson’s editing cuts into these interactions in media res and elliptically blots them out just as Harry’s conversation partner has clocked his insidious nature. It’s made pointedly clear that we don’t get to see the entirety of these interactions, and Glover tailors each scene to show how Harry worms under his conversation partner’s skin, leaving us to intuit the parts we don’t get to see. When he helps Junior with chores around the house, he warns about folks who help others for selfish reasons with a fatherly practicality. Junior looks visibly shaken by Harry’s words, which he might fairly be interpreting as insults against him and his wife, but the scene ends before he has time to respond.

But when Harry sits with Babe Brother and Linda, he flaunts a switchblade with a rabbit’s foot and a storied, violent history behind it, seductively transforming himself into the sort of commanding figure Babe Brother desperately wants to be. He tells them plainly that he believes not in sin but in Good and Evil, and that Evil must be worked at to be achieved. Glover’s conversational tone pitches this as an explanation for why he’s not at church, but it’s all too evident what he means by this. Glover’s performance also benefits tremendously from the little pinpricks of light cinematographer Walt Lloyd is constantly putting in his eyes, letting them glint with a history Harry is only interested in sharing on his terms.

Even as his behavior gets worse and his advice more destructive, Glover's affable mask never really drops. Glover continuously foregrounds Harry’s charm, using his charisma to hold court without sucking all the oxygen out of the room. And why would he, when so much of his influence comes from trading stories, imparting advice, making sure his words are really absorbed rather than spectated?

Everything that makes Glover a soulful, grounding presence in so many other films is expertly recalibrated in service of a man who uses niceties to hold others hostage. He's quick to put his hand on someone's shoulder, to wrap an arm around them like a dear friend. His welcome demeanor, expressive face, and gravelly voice are transformed into the sort of oily, ingratiating veneer you really want to hope is as friendly as it claims to be. His corrosive presence subtly creeps its way through Gideon and Suzie’s family, rather than loudly announcing itself something his hosts have to reckon with from the get-go. By the time he’s clipping his toenails in the living room and asking people to tend to him while a comatose man sits across from him, the cruel, baffling absurdity of how he inserted himself into this family’s home is plain as day.

Even better, the screenplay’s careful attention towards the family’s dynamics means we can’t regard him as merely creating these problems from thin air. There’s no doubt he’s speeding up events, exacerbating fault lines that have been subterranean for a long time, but the question of how much of this would have happened without him remains fascinatingly difficult to answer. As much as the film orbits Harry, tracing his influence onto the problems plaguing Gideon’s family, he’s not the origin of any of them. I won’t say how these problems are resolved, but the concluding message that Gideon and Suzie’s family have become stronger for weathering Harry’s stay rings truer than most movies like this really earn.

To this effect, To Sleep With Anger detaches itself from Harry for long stretches, as the family has to reckon with the mixture of mundane annoyances and mysterious events that have sprung up around him. The rest of the cast is strong enough to carry the film when Harry is gone, but it’s hard to argue that Glover’s performance isn’t the very best thing the film has going for it. It’s the sort of star turn that I wish he got the chance to do more often - flexing a singular stylization for longer than Sorry to Bother You or The Royal Tenenbaums allowed, acing a character who’s equal parts man and idea more thoroughly than in Beloved or The Color Purple necessarily give him room for. Glover’s work is a triumph no matter how you look at it, and I’m happy to watch it as many times as you’d like.