At last, we must say goodbye to the 1986 cinematic year. The Supporting Actress Smackdown was a blast and, before moving on to 1937, there's one remaining matter to take care of – the Best Costume Design Oscar race. Just like Dianne Wiest won the first of her two Academy Awards at that ceremony, so did Jenny Beavan. The British designer dressed the likely runner-up for Supporting Actress, Maggie Smith in A Room with a View, delivering a dream of Edwardian fashions with the help of fellow costumier John Bright. Indeed, all of the nominees that year were period pieces, ranging from 1500s Venetian tragedies to a time-traveling misadventure through 1960's suburbia. The contenders were:

- Anna Anni & Maurizio Millenotti, Otello

- Jenny Beavan & John Bright, A Room with a View

- Anthony Powell, Pirates

- Theadora Van Runkle, Peggy Sue Got Married

- Enrico Sabbatini, The Mission

First, let's examine the winner, our favorite and much-dissected Merchant-Ivory classic. I promise this is the last time I write about A Room with a View…

Since so much has been said about the E.M. Forster adaptation already, let's be quick. Sourcing from many London warehouses and costume shops, Beavan and Bright constructed a wardrobe made of vintage pieces and recycled garments from other projects. Despite their cost-cutting methods, the final product is as splendorous as it is character-specific. While historical accuracy isn't always the point of costume design, a project such as A Room with a View, a story focused on the behavioral specificities and social mores of a gone-by era, positively demands it. If one is to be immersed in the past, that resurrected time must feel palpable. Furthermore, clothing is a handy indicator of social hierarchies and age, financial situation, and the cultural references of any given person.

As the story is expressly set at a point of transition - a year before the Directoire style popularized streamlined designs - the fashion-forwardness of individuals lets us perceive their status, the importance of appearances in their lives. It's interesting to note, for example, how the mature women in Lucy Honeychurche's life have very definite tastes, like her mother's love for floral frills and cousin Charlotte's tailored garb with starched angular details. In contrast, the girl is experimenting. Sometimes she takes cues from the matriarch. Sometimes she tries on a discordant color. I love the pale blue ensemble that cuts across the warm tones of Florence and the fashion failure of a wild crimson topped with a silly hat. Lucy is discovering who she is, learning to stop lying and hiding behind masks of propriety. Her costumes reflect that.

The other Oscar nominee set in an Italy of the past is Franco Zeffirelli's Otello. Like the director's previous La Traviata, Verdi's opera is reimagined for the big screen. However, there's a big difference between the two projects. While the older flick tends towards a fantastic grandeur, stretching the Victorian environment to extremes of cinematic theatricality, Otello is more interested in realism. Zeffirelli materializes what, on stage, is abstract and shoots his actors through a collection of nervous close-ups. The opening storm, for example, is staged as an actual downpour, so much so that the epic singing can't help but look ridiculous. One wonders how the choir isn't gargling through the tune.

Realism and opera feel antithetical, and Otello does little to disprove that assumption. However, it looks opulent, from its real locations dressed with vertiginous scenery to the costumes that look like they came out of a portrait. Katia Ricciarelli's Desdemona is a Veronese painting come to life, adorned, as she is, in some of the best Venetian fashions I've ever seen on-screen. Because of their complex political system of city-states, the Italian style of the period tended to vary wildly from place to place. Those particularities demand research and an eye towards minutia – a mighty challenge. Thankfully, Maurizio Millenotti and Anna Anni are a genius team, capturing the sensual textures of Renaissance Art with intricate textiles and a complex color story.

While some might disagree, the best parts of Otello are its flightier flights of fancy, passages that momentarily abandon the grittiness of reality and soar into the heavens. Primarily, that manifests in spurts of eroticism, whether a masturbatory fantasy from Cassio or an obscene Iago leering at Christ's glistening body on the cross. Costume-wise, this is present in the tight men's garments, leather piping finding a middle ground between ancient aristocracy and contemporary fetish gear. As for the blonde victim of Othello's wrath, she's seen chiefly in pale silks, a beam of moonlight crystalized in a womanly shape. Way before she is brutally murdered, Desdemona already looks like a silvery ghost.

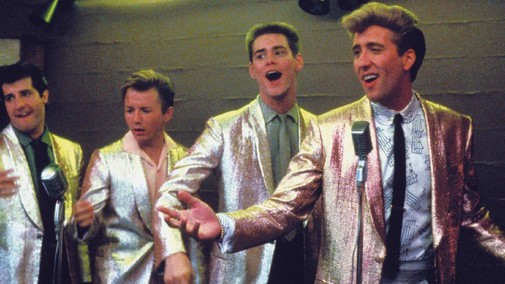

Theadora Van Runkle's creations for Peggy Sue Got Married follow a similar logic. Like most of Francis Ford Coppola's films from this period, the time-traveling narrative is constructed with astounding visual precision, evoking a world of soft pastels that slowly reveals a quirkier, darker edge. The fit of Kathleen Turner's costumes is divine, rendering the absurdities of cupcake silhouettes, fuzzy sweater vests, and poodle skirts with sculptural brio. While Peggy Sue is transported to the past, the land feels like a faded memory, color-coordinated into oblivion. Every person she comes across is like a facsimile of themselves, perchance a spirit. Moreover, the indulgent nostalgia isn't applied uncritically, for we see how the protagonist herself regards clothing as costuming.

Depending on who she's interacting with, the time-traveler tries on the look of a different person. This is seen from the beginning when she attends her high-school reunion in the metallic copy of an old dress. Later, when appealing to the younger version of her parents, she dons on girlish subdued outfits before trying on some dark hues when going out to have fun with a wannabe beatnik. It reaches a comedic apotheosis when Peggy discovers her grandfather's friends, and they all perform some magical ritual to send her back to the future. Then, the pastels give in to ridiculous parodies of academic garb, masonic clownery with a Hollywood twist. Love how the gown she wears then is finely pleated gold lamé, a counterpoint to the silver ruffles of her reunion confection.

Roman Polanski's Pirates feels much less controlled and curated when compared to Coppola's Peggy Sue Got Married. The stories of its chaotic production certainly make it seem so, and the final flick isn't anything special. Still, some greatness rises from mediocrity. Namely, it's the work Anthony Powell's, his decadent costumes which are a recreation of Baroque styles dripping in old lace, embroidery, period details that fill the frame with an overdose of visual information. It could be too much, but the result is akin to a storybook illustration full of cross-hatching. Like many Powell's period projects, there's a refined sense of historical research, exploded outwards through exaggeration. Pirates might be a nautical action-adventure, but it's more operatic than the Zeffirelli flick.

Then there's the textures, the aging, the sense of fine fabrics corroded by salty air, decrepit plumes and leather melted by the humidity of a stuffy ship. One look at the screen, and we can practically smell the characters. An excellent way to confirm the quality of Powell's efforts is to see them beside an achievement of similar purpose and lesser results. Enrico Sabbatini was a sound designer, but I'd argue that The Mission is far from his best work. Linens, cottons, clerical silks, and formal brocades don't appear to belong to the hot Amazonian setting. That could indicate a criticism of colonial presence, and there is some truth to that since the film makes vague gestures in that direction. The problem is that nothing feels authentic.

The materials' deterioration is a surface-level patina, with clothes often looking like they were put on the actors just before the scene. Well, of course they have, but they shouldn't appear so, not when Roland Joffe tries so hard to register the forest's celestial physicality, its people, its light. Then there's the friction between an attempt at historical narrative and design shortcuts present everywhere one looks. Notice the lack of delicate lace on Catholic vestments, out-of-place gowns that close in the back despite sporting a stomacher on the front. Sure, these are all nerdy concerns, but they do break from the picture's aesthetic register, its putative rigor. Maybe, like in Otello, reality should have been avoided altogether. However, unlike Anni and Millenotti, Sabbatini doesn't show much precision in his attempted realism.

Like the Oscars, I'd pick A Room with a View out of this bunch. But, if asked to compose a personal ballot, I'd also keep Peggy Sue Got Married and Pirates. In addition to that trio, let's consider the purposeful anachronism of Derek Jarman's Caravaggio. Sandy Powell's first movie is an inspired debut, showcasing her understanding of history, willingness to experiment, and a good eye for disruptive visuals. The film looks like a 17th-century painting not because it copies the painted subjects exactly. Instead, it conjures an ineffable mood, the stark contrast between blood-red silk draped over a severe black suit. Crimson carnality shines against funereal darkness, ancient symbols of wealth smacked right against a 1980s ready-to-wear purchase.

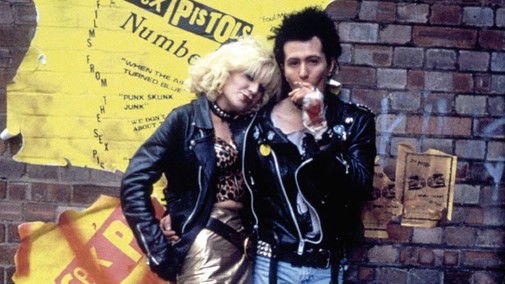

Another exercise in circumvented reality is the wardrobe Catherine Cook designed for Sid & Nancy. Punk fans have long criticized the movie for glamorizing troubled histories, varnishing gritty truth with a coat of Hollywood glitz. That's an inaccurate assessment, though I'd argue that's precisely why it works. Instead of documenting a tabloid story, director Alex Cox and his team create a fairytale of the gutter. A film where the lovers kiss under a slow-motion waterfall of garbage isn't exactly aiming for verisimilitude. Instead, Sid Vicious, Nancy Spungen, and all the other real characters are a dream of punk, a romantic nightmare that elevates life to myth. Like Powell in Caravaggio, Cook doesn't make copies. Instead, she makes an invocation of mood, of rarefied sentiment, using cheap leather, ripped fishnets, and holey t-shirts.

Now, dear reader, please share your dream Oscar ballots in the comments. Are you a fellow Jenny Beavan fan, or do your preferences lay elsewhere?